|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

August 14, 2004 - Issue 119 |

||

|

|

||

|

A $1 Million Boost for Indian Education in Minneapolis |

||

|

by Norm Draper Star Tribune |

||

|

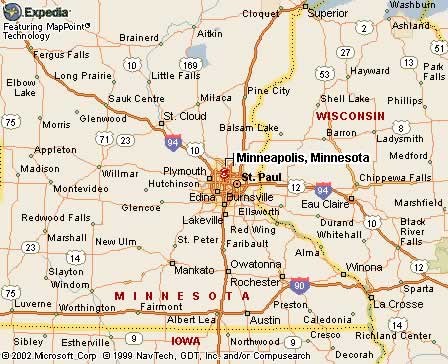

Operating out of a Lake Street storefront across the street from McDonald's, the place is a hive of teenage activity, with dozens of students -- mostly American Indians -- toiling away on the computers. Native Academy is at the forefront of efforts to raise American Indian student performance, so often weighted down by poverty and transience. It has a simple, overarching mission: To make American Indian kids better students with better prospects for life after high school. That work just got easier: The U.S. Department of Education announced this week that the school's parent organization -- Migizi Communications Inc. -- will get a million-dollar grant over three years. In the first year, Migizi gets $348,131. Amounts in the second and third years are slightly less. Graham Hartley, education directorTom SweeneyThat amount rivals the $1.1 million grant given to the entire Minneapolis School District for its American Indian programs. For Migizi, it's a big boost -- each year's grant amount is about one-third of the organization's annual budget, said its education director, Graham Hartley. Migizi administrators said the grant will enable them to launch a new emphasis on helping American Indian high school students in math, science, technology and engineering. President Laura Waterman Wittstock said such fields are keys to the nation's future, and American Indian kids have to get on that career elevator. "American Indians are just way down in terms of representation in those fields," Wittstock said. Signs

of success Hartley said there are signs the program is bearing fruit, and Minneapolis district statistics seem to back that up. School attendance for Native Academy kids is better than for other American Indian students in Minneapolis, and basic-skills test scores for Native Academy kids are higher than other American Indian students. For instance, Native Academy eighth- and ninth-grade passing rates were 20 percentage points higher on the state basic-skills math test than those for Minneapolis American Indian students who didn't attend Native Academy. Yet Migizi's Native Academy is not really a school. Its teachers mostly work in Minneapolis schools with other teachers in predominantly American Indian classrooms. They monitor homework assignments, talk to parents, and sometimes attend parent-teacher conferences because parents feel more comfortable having them around. Plus, the academy hosts after-school programs and offers a place where kids can come in and do their homework. While the program is aimed at American Indians, others are not excluded. Hartley said about 25 percent of the 250 young people served by the academy in Minneapolis secondary schools are non-Indian. According to Minnesota Department of Education statistics, there are 1,789 American Indian students at all grade levels in Minneapolis schools. Out of those, Minneapolis statistics show that 959 are enrolled in grades six through 12. The academy was started in 1995, but Migizi has been going since 1977. It was initially planned as a training program for American Indian journalists, focusing on radio. But as the years went by, the journalism gave way to an emphasis on education. The organization also operates a fitness program in the same building as the academy. Stating

their goals Kids who finish their summer Native Academy projects get $100. But academy administrators and teachers hope they will get something more -- a seamless transition from the eighth grade to that critical first year at high school. The students in this particular class are coming out of three Minneapolis middle schools and heading next month for the All Nations American Indian magnet program at South High School, which has the highest percentage of American Indian students of any Minneapolis high school. Despite the computer work that commanded students' attention, there is a social aspect to the program. The idea is to introduce the kids who will be attending South's All Nations program as freshmen next month to each other. "You can make new friends, so you already have friends when you get to high school," said Camille Papasodora, 17, who works at the academy as a mentor for the ninth-graders. |

|

|

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Vicki Barry and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

Mid-August,

and school is in session at Minneapolis' Native Academy.

Mid-August,

and school is in session at Minneapolis' Native Academy.