|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

July 31, 2004 - Issue 118 |

||

|

|

||

|

Success Story |

||

|

by KATIE PESZNECKER - Anchorage Daily News |

||

|

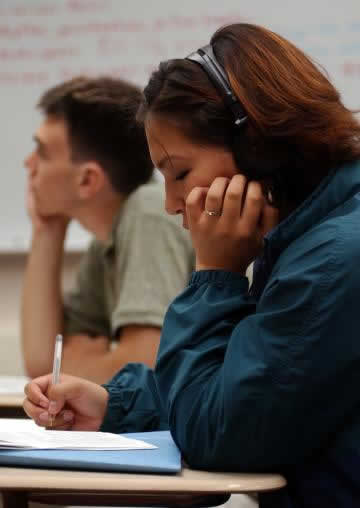

credits: (1) Corey Bunnell, 18, receives help from history teacher Dawn Gould during the Cook Inlet Tribal Council summer school program at West High. (2) Julia Pletnikoff, 18, studies U.S. media and government in Howard Sparrow's class during Cook Inlet Tribal Council's summer school program at West High.(Photo by Daron Dean / Anchorage Daily News) |

|

But for Jones, it was intensified. She had just moved to Anchorage from Kotzebue, the regional hub community of Northwest Alaska with about 3,000 people, mostly Inupiat. Her new school in Anchorage seemed huge, she said, with about 2,000 students and mazes of crowded hallways. "When I moved here, I was like, 'Whoa,' " said Jones, now a 17-year-old, soon-to-be senior. "It was really different, especially coming from a village. You're used to being with other people like yourself." By that, Jones means other Alaska Natives -- people who share her culture, her heritage, her identity, her experiences. Now she has found a way to connect to all that through school, by way of the Partners for Success program developed by Cook Inlet Tribal Council and the Anchorage School District. It started as a pilot program three years ago. Today, funded by federal grants, it has grown to four Anchorage high schools and four middle schools. More than 650 Alaska Native and American Indian students in the district took one or more classes through it this past school year. Its summer school program at West High School, which wrapped up earlier this month, drew about 100 teenagers from the district. The unique program aims to help students pass the exit exam, a three-part test in reading, writing and math that is required for a diploma. Tribal Council staffers and schools Superintendent Carol Comeau say the program is working, and they credit a passionate staff, small classes and a curriculum rich with Alaska culture and history. "They're showing that when you have appropriate staffing and you make an aggressive outreach to families -- to parents, to elders, to kids -- and you really focus on reading, writing and math, achievement improves," Comeau said. "They've blended the strong academics with the cultural values. It's obvious to me that it is paying off, because student attendance has improved, achievement certainly has improved." The exit exam has proved a barrier for many Native students. On average, they fail the test at a disproportionately higher rate than white students. This year, 627 high school seniors statewide retook the reading portion of the exam, and of the 428 who failed, about 54 percent of them were Native. About 43 percent of the 178 seniors who fell short on the writing part were Native. And of 554 seniors who failed the math section, roughly 42 percent were Native. Forty-five percent of seniors retesting in reading were Native students, as were 37 percent of seniors retesting in writing and 36 percent of seniors retesting on the math portion. Anchorage's Native students are emphatically beating the statewide trend. An estimated 95 percent of Native 12th-graders this year passed the exit exam. "This is a program we are building that is really working," said Gloria O'Neill, president and chief executive officer of Cook Inlet Tribal. "We know we're on the right track. I truly believe, as an Alaska Native, that our people will really achieve parity when we have great opportunities within education." Students in the program take courses heavy on discussion. Work is often self-paced, and students use hands-on methods and real-life applications. "We don't have students sitting in neat little rows," said Amy Lloyd, director of K-12 educational services for Cook Inlet Tribal. "Culture is the backbone of Cook Inlet Tribal Council. Our goal is for our students to graduate with real choices." Cook Inlet Tribal has people on staff whose sole job is to get families involved and keep them in the loop. Parents and guardians receive frequent updates on their children's progress and are told if the student isn't doing well. Families are also invited to potlucks and family nights, which have so far proved popular. At the first such event, Lloyd said, council staffers were hoping for a least a couple dozen people to show up. They got 350 family members. Teachers and other staff members with the program -- about half of them are Native -- will call parents and track a student down if the child is late or skips class. On the days that students took the exit exam, the staff members waited at their schools' front doors to welcome their students in. "The teachers are very concerned," Jones said. "Even if you're tardy, they call your parents. They called my house at like 8:30 a.m. once. I was like: 'I'm coming! I just woke up!' They really want our students to succeed." Jones, who will be a senior at East High in fall, hadn't thought much about life after high school when she came to Anchorage. She met with program counselors, who told her about scholarships. In Kotzebue, she said, "you don't have anything to hope for. You think you'll just be stuck there your whole life. I didn't think I was going to go to college." Now Jones plans on going to college and becoming an Air Force pilot and airplane mechanic. She said her education is on track and summer school is helping maintain that. Her independent reading course helped her catch up, while her U.S. history class helped her get ahead, she said. Classes are small, Jones said. "And they let you go at your own pace. You can just take your time. You're not forced into anything."

"Like in U.S. history, we're talking about the pipeline and how it's affected the economy," she said. "They have taught us about things that are relevant, that could actually affect us." Making some of the classes relevant is unnecessary because they already are. Course offerings include Native art, Yup'ik language and literature of the North. But the majority are core courses, from writing to advanced composition to algebra. Alice Metz, a math teacher with the program, said blending culture and history into the curriculum to make it more relevant to students isn't difficult. In math, when teaching positives and negatives, she uses tides as an example. For more complicated equations, Metz may ask her students to figure out how much gas and food they'll need for a hunting trip, depending on what route they take. In summer school, Metz uses problems like these to work on students' weakest areas and help prepare them for the coming school year, she said. "Most of the students have been telling me that they're learning more through the summer school program than in the whole school year," said Metz, originally from the Yup'ik village of Tununak on Nelson Island on the Bering Sea coast. "We care about our students, and we're devoted to our students," Metz said. "They're open to me too." Roland Ivanoff, 18, took Metz's morning class this summer. Ask Ivanoff how he feels about math, and he first sighs. "I can do all the work in my head," Ivanoff said. "But I can't show it. I'm here to try to learn how to show how I get from point A to B." It's easier to figure this out in the summer program, he said. There's plenty of one-on-one time with teachers. "You don't have a room full of 30 students and all of them are saying, 'I need some help,' " Ivanoff said. He has passed all parts of the exit exam but needs better math grades to graduate. He's fixed on getting a diploma and getting into the Navy. "I need to finish my credits. No GED for me. I want a diploma." |

|

|

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Vicki Barry and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

It

helps also that the topics are actually things people here care

about, Jones said.

It

helps also that the topics are actually things people here care

about, Jones said.