|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

May 22, 2004 - Issue 113 |

||

|

|

||

|

Storybooks From '20s-'50s for Native American Kids Reviewed |

||

|

by David Steinberg - Albuquerque (NM) Journal Staff Writer |

||

|

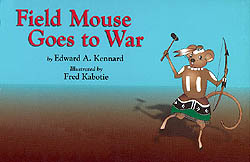

credits: graphic 1: "Native American Picture Books of Change" cover; graphic 2: "Field Mouse Goes To War" cover |

|

There she is in a black-and-white photo on page 127, a woman with a soft smile looking up at the camera, taking a break from painting. This is not just any artist. This is the famous Pueblo artist Pablita Velarde.

With the publication of Velarde's book "Old Father, the Story teller" in 1960, Benes said, she "was one of the first Native Americans to attempt to write and paint her own culture, bringing the stories and art of Santa Clara Pueblo to a wider American culture." Benes quotes Velarde as saying that she did the writing because "I thought it would be a good thing if an Indian wrote an Indian book." Velarde is one of many Native American artists— and a handful of writers— whom Benes spotlights in her revealing, comprehensive overview of a previously undiscovered period in American literature. The literature encompasses books for children illustrated by Native Americans and largely penned by Anglo writers. The period is the 1920s to the late 1950s. Starting in the 1930s, the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs began publishing many of these collaborations as bilingual textbooks, "and they were the first bilingual materials published on any large scale in this country," Benes said in a phone interview. This was a time of change. The BIA was just beginning to allow Indians to speak their own languages, Benes said, because until then Congress had mandated total assimilation. So the BIA's bilingual textbooks, published in four series under the rubric of Indian Life Readers, was considered revolutionary, she said. One series was in English and Sioux. Another was in English and Navajo. Benes said it wasn't until the 1930s that the BIA had created the orthography for what had been only an oral language. A

third series, in English and Spanish, was for the Pueblo Indians.

Benes explained why Spanish was used. "There were so many languages that I think they came to the conclusion it was easier to do the books in Spanish," she said. "Many Pueblo Indians spoke Spanish as a second language and there were some Pueblo languages the Indians did not wish to have written." A fourth set was in English and Hopi. This series, however, had Hopis writing the text in Hopi as well as doing the illustrations.

But one of the first children's books with illustrations by Native American artists— pre-Indian Life Readers— was published commercially. In 1922, Harcourt Brace & Co. released "Taytay's Tales, Folk-Lore of the Pueblo Indians." Kabotie, then a student at Santa Fe Indian School, did most of the illustrations, and Otis Polelonema, a classmate of Kabotie's from Second Mesa, did some drawings in the book, according to Benes. Elizabeth

W. DeHuff, wife of the school's new superintendent, collected and

retold these animal stories in the anthology. "We didn't do especially well. We opened in the late '80s when oil prices had fallen and Denver was in a real recession. We stayed open just for a few years," she said. Benes

also taught English and children's lit at Arapahoe Community College

and was a librarian at a private school. Her

research on "Native American Picture Books of Change"

began about 15 years ago and has involved visits to several national

archives, to libraries and museums. "Librarians,

archivists and curators have given me a lot of help. Sally Hyer,

the manuscript editor, was a mentor to me. She died last year,"

Benes said. Another

person who aided her was Albuquerque resident Robert W. Young. He

and William Morgan created the Navajo alphabet, she said. "He's

helped the Navajo immeasurably and helped me greatly," Benes

said. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

But

author Rebecca Benes said in her new book "Native American

Picture Books of Change," that Velarde was also a literary

pioneer.

But

author Rebecca Benes said in her new book "Native American

Picture Books of Change," that Velarde was also a literary

pioneer. The

first in this series was the 1944 "Field Mouse Goes to War."

Hopi Fred Kabotie did the illustrations. Albert Yava wrote the Hopi

text and Edward Kennard, who had developed a phonetic alphabet for

the Hopi, did the English, Benes said.

The

first in this series was the 1944 "Field Mouse Goes to War."

Hopi Fred Kabotie did the illustrations. Albert Yava wrote the Hopi

text and Edward Kennard, who had developed a phonetic alphabet for

the Hopi, did the English, Benes said.