|

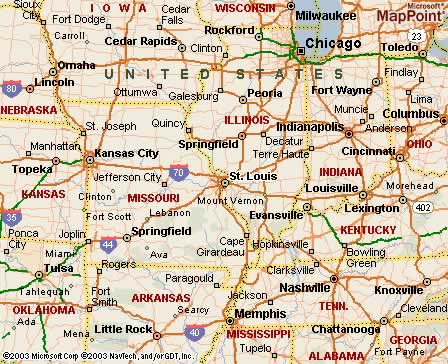

Art

of the Osage, organized by the Saint Louis Art Museum, is the first

major exhibition to explore the art and culture of the American

Indian people known as the Osage. The exhibition also brings focus

to the vibrant story of the Osage, whose history traces to the great

Mississippian culture of North America. From the 17th to the 19th

century, the Osage inhabited the Upper Louisiana Territory amid

the Mississippi, Missouri, Osage, and Red Rivers, where their formidable

presence was significant in the country's westward expansion.

The

Saint Louis Art Museum presents Art of the Osage in a year celebrating

the bicentennials of the Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark

expedition as well as the centennial of the 1904 World's Fair in

St. Louis. The exhibition opens in the midst of the Three Flags

Festival commemorating the formal transfer of the Louisiana Territory,

which occurred in St. Louis on March 9-10, 1804. Representing the

Osage people at the event, Principal Chief of the Osage Nation James

Roan Gray will mark the seminal role of the Osage in the history

of the United States.

The

refined artistic tradition of the Osage reflects the sense of continuity

and purpose that has long united the Osage people in the values

of spirituality and community. Rich in meaning and complex in its

commitment to tradition and utility, Osage art is infused with aesthetic

vigor bound to exquisite simplicity.

Unlike

nomadic tribes, the Osage lived in permanent homes, cultivating

the bounty of the prairies, woodlands, and plains. For more than

a century before the Lewis and Clark expedition, the Osage controlled

nearly half of the region's fur trade. The dominance of the Osage

in this land of rivers, fiercely protecting its abundant natural

resources, was an important factor in the founding of St. Louis

in 1764. So significant was their influence that Meriwether Lewis

arranged for several Osage chiefs to travel to Washington in 1804

for an extended visit with President Thomas Jefferson. The Osage

homeland is now centered in the rich oil lands of Oklahoma, where

the last Osage reservation was established in 1872. There the Osage

continue to preserve the vitality of their artistic and cultural

traditions, while prospering in the business and political arena

of contemporary America.

The

"purposeful beauty" characteristic of the Osage aesthetic

is evident in the more than 100 objects featured in the exhibition.

The works of art come from public and private collections in the

United States and Europe and were selected according to the highest

aesthetic standards with the guidance and support of the Osage community.

Interpretive and contextual materials were developed in collaboration

with active Osage historians and artists. With objects spanning

250 years, the exhibition encompasses two major periods of Osage

art: the Old Era (1750-1900) and the New Era (1900 to the present).

Works

of art from the Old Era include objects created for child rearing,

hunting, domestic industry, and warfare. Highlighting the domestic

arts and child rearing are objects such as hand-carved cradle boards

decorated with brass bells and finger-woven straps, as well as dolls

dressed in high Osage fashion. The hunting arts are exemplified

by dramatic split-horn headdresses with trailing horse hair and

feathers. A group of boldly painted shields, riding quirts, and

war clubs illustrates the level of artistry dedicated to the accoutrements

of warfare. A particularly rare riding quirt depicting a warrior

with a bow and spear shows how quickly Osage artists adopted the

pictorial style of artists such as the notable Karl Bodmer, who

collected the quirt in 1834.

The

New Era is represented through the defining activities of the modern

Osage, including the In'Lon Schka dances, weddings, the War Mother's

Society, and the Native American Church. The arts of the New Era

reveal the strength of tribal identity in brilliantly colored and

patterned sashes, stunning beaded vests, feast bags, and silver

ornaments, all made for the In'Lon Schka dances. Plumed hats, ornate

military dress, and refined horse regalia represent the Osage wedding

arts. A particularly wonderful Osage wedding coat demonstrates how

Osage artists adapted western apparel using ribbon appliqué,

horse hair, and trade cloth to create elegant and masterful works

within the Osage aesthetic tradition. The War Mother's Society is

represented by a group of blankets with images of planes, tanks,

and flags that are woven, beaded, and sequined. The importance of

the native American Church is illustrated with fine examples of

sacred staffs, peyote fans, and rattles.

A

fully illustrated exhibition catalogue, published by the Saint Louis

Art Museum and the University of Washington Press, includes rare

black-and-white historical photographs dating from the 1870s as

well as excerpts from recorded interviews with members of the Osage

Nation. Catalogue contributors include exhibition curator John Nunley,

the Morton D. May Curator of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the

Americas at the Saint Louis Art Museum; Garrick Bailey, professor

of anthropology at the University of Tulsa; Daniel Swan, senior

curator of the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa; and Sean StandingBear,

Osage oral historian and artist. Cultural reviewers for the catalogue

are Kathryn Red Corn, director of the Osage Tribal Museum, and Leonard

Maker, distinguished Osage elder. The project has been strongly

supported by Principal Chief of the Osage Nation James Roan Gray

and former Principal Chief Charles Tillman, Jr.

Through

August 8, 2004

Shoenberg Exhibition Galleries

General Admission: $10

Seniors & Students: $8

Children (ages 6-12): $6

Members & children under 6: Free Admission is free to all on

Ford Free Fridays. Each paid admission includes an audio tour. Audio

tours are available on Fridays for $3 and are free every day for

Members. For ticket information, please call (314) 655-5299.

Generous

support for the Art of the Osage exhibition and catalogue has been

provided by The Henry Luce Foundation, The Edward L. Bakewell Jr.

Fund, and The Aileen and Lyle Woodcock Fund for the Study of American

Art.

|

Shield

1900

Approximate

Diameter: 24 in. (61 cm)

hide, feathers, cloth, metal, and pigment

Osage Tribal Museum

Warfare

The Osage went to war only after careful deliberation and

ritual preparation. The smoking of a sacred pipe symbolized

consensus among the clans, whose priests, chiefs, officers,

and warriors then selected the time and place to attack. Osage

war parties struck with lightning speed and delivered deadly

blows to their adversaries. This ensured that there would

be no chance for the enemy to regroup, and it communicated

to other tribes the dangers of encroaching on Osage territories

and resources.

Battles

often took place on horseback, when weapons included rifles

as well as bows and arrows. In hand-to-hand combat, warriors

used clubs with deadly blades. Osage warriors protected themselves

with shields that were imbued with sacred power and used riding

quirts to encourage their horses to full speed. They wore

ritual dress and applied black paint, representing death,

to their faces. Their red and black headdresses, known as

roaches, stood for the destructive nature of prairie fires

and the ashes left behind. The lone feather of a roach headdress

represented the Osage warrior who stood tall amid death and

destruction.

|

|

|

|

Cradleboard

1930-1940

11

x 12 x 40 1/2 in. (27.9 x 30.5 x 102.9 cm)

wood, brass, beads, brass bells, yarn, paint, and cloth

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Child

Rearing

The most valued people in Osage society are children. The

strong sense of order among Osage people traditionally has

resulted in strict rules concerning the rearing of children

according to gender and birth order. In previous generations,

firstborns of either gender were educated to become community

leaders, while their siblings were brought up to take service

roles.

Infants

were tended by their mothers, who kept them safe on cradleboards,

soothing them with the sound of bells and entertaining them

with dazzling beads and finger-woven pieces. As toddlers,

girls played with toy cradleboards and dolls that they learned

to dress in proper male and female attire. Boys played with

pull toys and model bows and arrows, which helped them prepare

for their adult roles. Young boys were ritually dressed at

dances to indicate their social development. In addition to

the child's parents, many relatives and clan members were

involved in the raising of children to help ensure the success

of the next generation.

|

|

|

|

|

Bear

Claw Breastplate

1900

Approximate:

18 x 10 in. (45.7 x 25.4 cm)

bone, bear claws, hide, and metal

Osage Tribal Museum

Domestic

Industry

Osage men and Osage women contributed to domestic industry.

Women were more concerned with everyday dress and accoutrements,

while men produced objects related to warfare and other sacred

rituals.

Hunters

supplied hides, bone, sinew thread, and fur to the women after

the bison hunts. Other materials for domestic industry were

secured from European fur traders who offered beads, trade

cloth, metal, paint, and silks in exchange for hides. Women

prepared the hides through a process known as brain tanning.

This was a technique in which brain matter from the animal

was spread on the stretched hide until it became soft and

supple. After this process, the women cut the hide into shapes

and sewed it into leggings, bags, and moccasins. Many items

were decorated with glass beads, wool, quillwork, and paint.

Items intended for ritual use, such as clan priest turbans,

incorporated materials considered sacred, including otter

fur, bird beaks, and feathers.

|

|

|

|

Bison

Headdress

1900

28

3/8 x 15 3/4 x 7 7/8 in. (72 x 40 x 20 cm)

bison hide, horn, feathers, beads, and brass

National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution

Hunting

In the Old Era, hunting was necessary to provide food, fur,

and other commodities for use among the Osage and for export

to the world market. Hunting expeditions for bison were conducted

in late spring after squash, beans, and corn had been planted

and again in the early fall after the crops had been harvested.

The power and temperament of bison made the hunt a dangerous

enterprise, and competing tribes on the hunting grounds presented

additional dangers to the Osage.

There

were strict rules imposed for the hunt. A chain of command

determined who would strike first, who had rights to specific

animals, and how the various pieces of the animals were to

be distributed. Hunters on horseback frequently used short

bows to wound the bison, while hunters on foot used long bows

to deal the lethal blows.

While

little is known about the ritual preparations for hunting,

pictorial records indicate that men of other Indian tribes

wearing full bison dress and horned headdresses danced to

entreat the bison spirits to give of themselves and feed their

people.

|

|

|

|

|

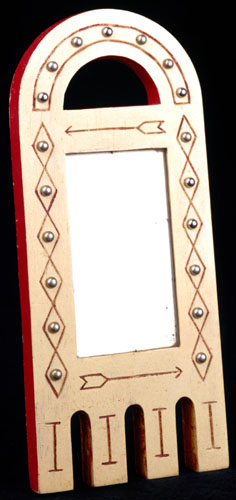

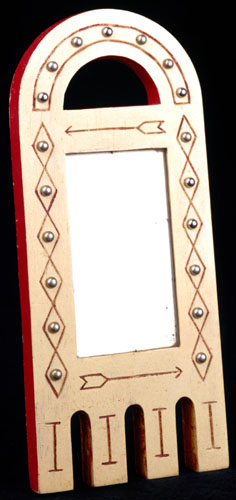

Mirror

Board

1900

13

x 6 x 1 in. (33 x 15.2 x 2.5 cm)

wood, metal, paint, and glass

Osage Tribal Museum

E-Lon-Schka

The Osage have always understood dancing as a tradition that

unites the community and provides a sense of social identity.

As Osage leaders looked for new ways to celebrate Osage identity,

they became interested in the contemporary dances of their

sister tribes in the region. Two of those tribes-the Ka and

the Ponca-transferred their drums and dances, including the

E-Lon-schka, to the Osage people at the three Osage villages

of Gray Horse, Hominy, and Pawhuska. The E-Lon-schka dances

became central to Osage ritual and communal life. Today the

dances are held on three weekends in June, one at each of

the Osage villages.

The

E-Lon-schka dances take place on an earthen floor under an

arbor consisting of a large, corrugated roof without walls.

Singers gather around the drum at the center of the arbor.

Male dancers in traditional dress move counterclockwise around

the drum. Headdresses, leggings, tail pieces, vests, moccasins,

belts, silver body ornaments, and ribbon shirts constitute

typical dance suits. Later, the women and young girls enter

the arbor, dressed in skirts and blankets decorated with colorful

ribbonwork. Their subtle and stately movements are in strong

contrast to the animated and athletic dances of the men. The

Osage embrace the E-Lon-schka dances to solidify their community

and pass Osage traditions on to their children.

|

|

|

|

Wedding

Coat

20th century

42

x 61 in. (106.7 x 154.9 cm)

wool and silk

Denver Art Museum Collection, Native Arts Acquisition funds,

1963.157

Weddings

In the Old Era, weddings were arranged between clans of the

opposite sides of the tribe. For example, a bride from the

Sky people might be matched with a groom from the Earth people.

Today many Osage marry for romantic reasons, frequently outside

the tribe. Horses used to be the gift of choice for special

occasions and dowries, but fine Pendleton blankets and cash

are more popular today. Brides and their bridesmaids still

dress in military-style suits with ribbon appliqués,

finger-woven sashes, and ostrich-plumed hats. Many Osage couples

now prefer to be married wearing Western-style clothing and

in Christian churches. The children of Osage unions are taught

the Osage way which they, in turn, will adapt to changing

times.

|

|

|

|

|

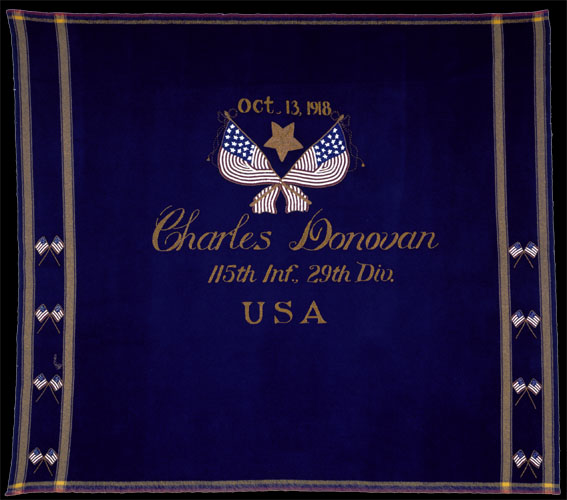

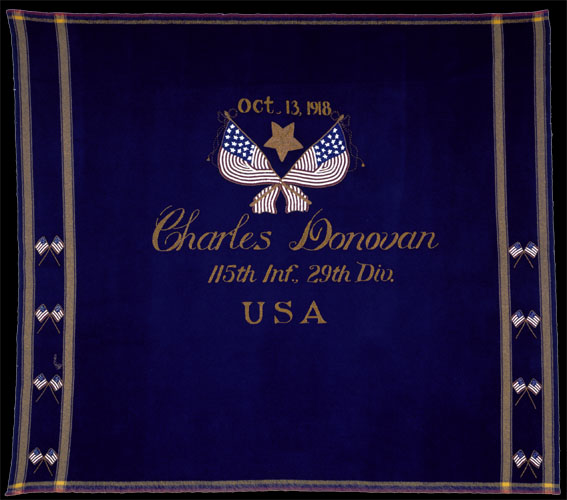

War

Mothers Blanket

1900

77

3/4 x 59 in. (197.5 x 149.9 cm)

wool, cloth, and glass beads

Osage Tribal Museum

War

Mother's Societies

Following World War I, the Osage found a way to honor their

sons and daughters who had served in foreign wars. They developed

the War Mother's Societies, which sponsor Soldier Dances.

These events replace the old dances associated with warfare.

Soldier

Dances are held on the Saturday before Mother's Day and on

Veterans Day at the various VFW lodges in Osage County. The

ceremony begins as the flags are presented to those seated

at tables along the walls. This is followed by women dancing

to celebrate the bravery and commitment of their sons and

daughters. The dancers wear beautiful blankets decorated with

patriotic symbols and emblems. Names of soldiers and their

units may also be stitched or appliquéd on the blankets,

which are treasured by families in the community.

|

|

|

|

Gourd

Rattle

1900

25

x 3 x 3 in. (63.5 x 7.6 x 7.6 cm)

glass beads, copper, brass, bronze, gourd, protein combination,

and plastic

Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution

Native

American Church

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, a new religion swept

through many American Indian societies. Known as the Native

American Church, it combines elements of Christianity with

many of the rituals and traditions of older Indian religions.

Osage elders adapted this religion to suit their own purposes.

Consistent with the Old Era religion, the new church was laid

out along the east-west path of the sun, with the door to

the church opening to the east.

Services

are held to celebrate the special occasions of life and to

soften the hardship of death. In ceremonies that begin at

sundown, men sit around a fire, talk, and sing songs to the

accompaniment of a drum. Women and children seated along the

church walls observe the service. Feather fans are used in

blessings. Gourd rattles with beautiful bead decorations,

drums, singing, and the crackling of a sacred fire at the

center of the church create a richness of sound. After the

meeting, members, relatives, and invited guests conclude the

service with a meal.

|

|

|