|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

April 17, 2004 - Issue 111 |

||

|

|

||

|

Nets & Paddles: Fish and Canoes Carry Meaningful Lessons |

||

|

by Rhonda Barton NW

Regional Educational Laboratory

|

||

|

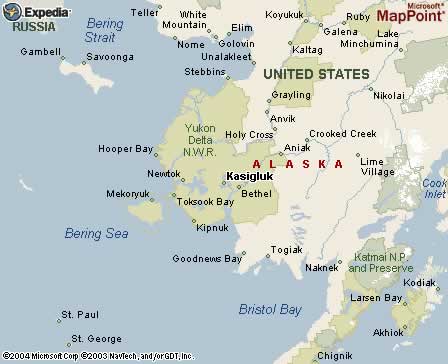

Aerial View of Kasigluk

|

|

"Only catch enough

fish to last you through the winter. Use and/or preserve every part

of the fish that is edible. Fish are easy to spoil, especially the

whitefish, so take care of the fish as soon as they are caught.

If we are lazy and idle, food won't come to us."

In this barren Southwest Alaska landscape, where temperatures dip to minus 40 degrees and permafrost dwarfs the growth of trees, water is a life-giver. Making up 10 percent of the village's 12-square-mile area, water is a primary source of food, an income generator, and a way to travel from one place to another. It's no wonder then that water—and the fish that live in it—make their way deep into the curriculum of Akula Elitnauvrik or "Tundra School." The school, with its own warehouse stocked with a year's worth of cafeteria lunches barged in when the weather is good, has just under 100 pupils. All but one, a teacher's child, are Alaska Native. From kindergarten through 12th grade (or "phase" in this ungraded school), students study things that prepare them for life in a harsh environment and connect them to the subsistence culture. Uses of fish parts, where edible plants grow, traditional ways to prepare for winter, how animals move: They're all part of thematic units that blend modern state standards with Yup'ik traditions that stretch back thousands of years. "We asked our elders what they wanted us to teach our students," says Levi Ap'alluk Hoover, who grew up in the village and has taught here for 25 years. "They came up with the topics and then we (teachers) came up with the units." Kasigluk was the first school to implement the Yup'ik cultural curriculum that's now found throughout the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. "For our students to only learn about skyscrapers and cows would be dumb," admits Principal Felecia Griffith-Kleven. "This curriculum validates the traditional lifestyle, helps them appreciate it, and teaches them the skills they need to be successful in the community." Griffith-Kleven, who grew up in Illinois but was inspired to move to Bush Alaska by her second-grade teacher's stories, says her school's goal is to produce students who can succeed in the local culture, as well as outside it. "They should be able to choose, and if our graduates leave to learn a trade or profession, we hope they will bring that knowledge back to the Delta and have the best of both worlds." Indeed, a 2003 statewide study of Native perspectives concluded that "subsistence is overwhelmingly important to Alaska Natives in both rural and urban areas, and they believe it will continue to be important in the future." Of those surveyed by the Alaska Humanities Forum and the McDowell Group, 85 percent rated subsistence as important or very important to their households. Dr. Oscar Angayuqaq Kawagley, a leading Native educator at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, believes "it is essential for Native students to receive an education that is clearly tied to their cultural worldview." He observes, "Although non-Native people tend to view the subsistence way of life (as) being very simple, the Native practitioner sees it as highly complex. A subsistence-oriented worldview treats knowledge of the environment and each part's interdependence with all other parts as a matter of survival." From

Akakiik to Manignaq Down the hall, which is lined with photographs of elders, Caroline Ataugg'aq Hoover—Levi's wife—tests kindergartners on the parts of fish. They enthusiastically shout out the Yup'ik names, as she waves laminated flash cards in the air. The children then move on to the next activity, picking up strips of construction paper and weaving them into a "lake" where cut-out pictures of lush (manignaq) and pike ('luqruuyak) can swim. Youngsters in phase 5/6 create illustrated books on boating safety and study the life cycle of whitefish (akakiik), one of four indigenous species. Levi comes in to lead a Yup'ik studies lesson, and plastic needles and skeins of mesh start tumbling out of kids' desks and backpacks. Soon everyone is industriously turning out chains of three-and-a-half-inch squares that grow into fish nets. Nicholson proudly holds up the results of three hours' work. What's the secret to his net-making prowess? "Being a boy," he shyly confides. For Levi, there's a stark contrast between the cultural lessons he shares with pupils and his own formal education. Attending a Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school, he painfully recalls that students were "severely punished" for speaking Yup'ik. "They washed our mouths out with soap, slapped our hands with a ruler, and made us stand in the corner." He vowed, if he became a teacher, to never treat his students that way. Not only did he earn a teaching certificate—after 13 summers of attending university—but he and Caroline have seen four of their six children go on to college so far. "We have to keep kids interested and motivated," he knows, "any way we can." The

Pull of Tradition How did the First People fell mighty trees and build sturdy canoes without chain saws or axes, he asks? Students venture guesses—"fire, sharp sticks, rocks"—and then go on to pose their own questions about canoes. "Why don't they sink?" wonders Nicole. "How many people can they hold?" Paul adds. Dennis pipes up, "How long do they last?" Soon, there's a list of 15 guiding questions that will shape assignments for the weeks to come. Students will research and record the answers in their individual tribal notebooks. They'll create miniature models of the river canoe found throughout the Northwest and compare this to the many canoe types that traveled along the inner and outer coastal waters. Using historical sleuth work, the class will investigate the types of canoes in turn-of-the-century photographs, increasing their perspective about their ancestors and the ways they built and honored the canoe. To Gilstrap, a strapping man with a ponytail and carefully waxed mustache, studying canoes here in the Puget Sound is a "no-brainer." Although this tribal school sits among berry fields in the shadow of Mt. Rainier, the jagged coastline of the Sound is only about a dozen miles away. And, even villages in the region's high mountain valleys used canoes to transport goods to settlements on the Sound and the Pacific. The starting point for Gilstrap's inquiry-based lessons is "Canoes on Puget Sound: A Curriculum Model for Culture-Based Academic Studies," developed by educator/author Nan McNutt and Washington MESA (Math, Engineering, Science Achievement) at the University of Washington. The curriculum blends language arts, history, health, and most particularly, math and science. It's designed to engage all learners but resonate especially with Native students. "What this curriculum does is to center the study on a cultural object," says McNutt. "This presents a platform for academic studies from which students also examine their own questions about the canoe to formulate a total understanding." Making

It Personal Taking pride in such accomplishments is a theme that constantly resurfaces. From canoes to the handmade drums that poke out of students' cubbyholes and the "Salmon Society" regalia that Gilstrap uses to reward good attendance and completed homework, Native culture is embedded in the classroom and throughout the 643-student school. Three times a week, the beat of the sacred drum reverberates through Chief Leschi's hallways as boys and girls start their day with a traditional circle. Kindergartners to sixth-graders all join in the songs and chants and dances. "We have to give our kids back their identity, because they've been stripped of it," says Principal Bill Lipe, who identifies himself as "Tsalagi," the Native translation of Cherokee. "For 150 years, Indians were told how to live their lives. Call it assimilation or call it genocide. We're trying to salvage what we can, which means going back and teaching the old ways while living in a contemporary world." "I've had more families thank me for allowing their child to learn about canoes, make a drum, tell a story," Gilstrap remarks. "It's exciting when I can share these things and see a light come on." FYI: For more information about the "Canoes on Puget Sound" curriculum, see NW Education Online, www.nwrel.org/nwedu/ 09-03. Consider

This

Such beliefs are woven into the thematic unit on fish, developed by the Lower Kuskokwim School District. Nita Rearden, an LKSD education specialist, worked with teams of teachers to develop units on a dozen themes: Some are used, as is, by all the district's 27 schools while others are adapted to reflect local traditions. The subjects cover everything from family and community to celebrations, storytelling, plant and animal life, land, geography, and weather. Bridging Western and Yup'ik culture, the material uses the child's background knowledge to explore social studies, science, literacy, and language arts. "It serves as an anchor and helps the learner become a powerful thinker in understanding other cultures—whether through books, videos, television, or radio," says Rearden. "If a child understands what a moose is, she can find out what an elk is, and even compare it to an elephant, even if she's never seen one." Rearden adds, "My hope is that we'll make children feel good about themselves and feel curious enough so they'll want to learn." The thematic units—and an extensive line of bilingual and Yup'ik storybooks, CD-ROMs, posters, and literacy materials—are available for purchase from the Lower Kuskokwim School District. You can find their catalog at www.lksd.org. |

|

|

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

KASIGLUK,

Alaska, and PUYALLUP, Washington—Flying into Kasigluk in a

"puddle jumper," miles of red and yellow-flecked tundra

unfold below you. A spidery network of lakes glistens in the autumn

sun and the Johnson River cuts a wide swath, slicing the village

into "old" and "new" sectors.

KASIGLUK,

Alaska, and PUYALLUP, Washington—Flying into Kasigluk in a

"puddle jumper," miles of red and yellow-flecked tundra

unfold below you. A spidery network of lakes glistens in the autumn

sun and the Johnson River cuts a wide swath, slicing the village

into "old" and "new" sectors.