|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

April 17, 2004 - Issue 111 |

||

|

|

||

|

Charter School Keeps Native Language Alive |

||

|

by Rhonda Barton Northwest

Regional Educational Laboratory

|

||

|

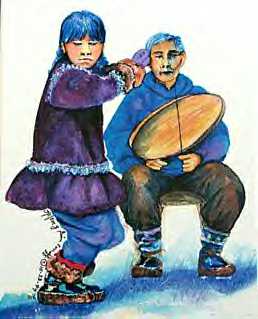

Learning to Dance by

Helen Jane Simeonoff

|

|

In Jones's sunny corner classroom, the "ACEs" take the place of ABCs: There are no B's or D's in the 18-letter Yup'ik alphabet. Student names like Angilan, Utuan, and Eveggluar call out from self-portraits that adorn the walls. And, the Pledge of Allegiance is the "pelak." Looking around, Jones remarks, "Every day our students are reminded that they're Yup'ik. They say 'we have life.'" Yup'ik, spoken by the Native people of Western Alaska, is the strongest indigenous language group in the state. The geographic isolation of the region helped keep English at bay longer than in other parts of Alaska, according to Walkie Charles of the Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Yup'ik phrases remain at the heart of the subsistence culture—"yuungnaqsaraq" —and 51 percent of the children in the region are classified as Yup'ik-speaking. Despite that, fluency becomes more tenuous every year as television and pop culture wash over the tundra. That fact fills Jones and her fellow immersion teachers (called "elitnauristet") with resolve and an almost religious fervor. They battled a skeptical local school board to establish their elementary program in 1995, after five years of study and lobbying. In 1999, they successfully applied for charter school status from the Alaska Board of Education in an effort to gain more autonomy and secure grants for the development of materials. Now they are gearing up for their charter renewal, ready to battle critics who question whether students are best served learning in their ancestral tongue or in the language that dominates the modern economic landscape. "We do have ignorant community members who think we're trying to go back to the old way of life—to using kayaks and living in sod houses—rather than trying to integrate the Western and Yup'ik cultures," says co-principal Agatha Panigkaq John-Shields. "When we hear negative comments from our opponents, we use that as a critique and strengthen our program. We show them, rather than fight," she adds with steely determination. While Ayaprun Elitnaurvik is the only Yup'ik immersion school in the Lower Kuskokwim School District (LKSD), 22 of the district's 27 schools have strong Yup'ik programs and one offers Cup'ig immersion. "What empowers people out here is the choices they have," notes Abby Qirvan Augustine, another one of the school's founding members. "The district doesn't direct villages to have certain kinds of programs." LKSD also produces a wealth of Yup'ik storybooks and instructional materials that find their way into classrooms throughout the state. The

Lower Kuskokwim School District has created colorfully illustrated

books to increase Yup'ik language proficiency. Jones's voice rises with excitement as she explains the difference between teaching in a traditional classroom versus an immersion program. "Most of it is total physical response," says Jones, the winner of a Milken Family Foundation National Educator award. "You use your whole body to demonstrate concepts, from the simplest to the most complex." Her fellow teachers—Abby, Carol, Sally—chime in with their own descriptions: "heavy on hands-on, a lot of singing, repetition, chants." They stress a "natural approach" to language acquisition—using Yup'ik in everyday situations rather than emphasizing formal rules and grammar. While the teachers maintain that their students achieve at higher levels than peers in English-only programs, the data aren't quite that cut-and-dried. Bev Williams, LKSD's director of academic programs, acknowledges that "English isn't the only factor," with attendance, parental support, and social issues contributing to test scores. "Longitudinal research indicates that students who begin literacy and academic instruction in their indigenous language, as they learn English, and then transfer into English do much better academically on English tests in the upper grades," notes Williams. "Also, students in good immersion programs tend to do better academically in English in upper grades." However, Williams continues, "The research is unclear on what happens if students enter an immersion program as limited English speakers and their only instruction is in the target or second language." Still, whatever the end result, it's undeniable that pride ripples out from these classrooms like a pebble thrown in the dusky Kuskokwim River. Parents who were never taught Yup'ik are beginning to pick up words from their schoolchildren. Elders beam at the students who perform traditional songs and converse in Yup'ik on visits to the nearby senior center. "(For

me) walking into the halls of Ayaprun is like coming home,"

says Charles, one of the recipients of a million-dollar grant for

a career ladder program for Yup'ik paraprofessionals. "Ayaprun

Elitnaurvik's success comes from the commitment of teachers like

Loddie and Abby who are truly Yup'ik, who are academicians, and

who (can) take ownership and orchestrate something as powerful and

as humbling as a Yup'ik immersion program." |

|

|

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

BETHEL,

Alaska— Though she stands barely five feet tall, Loddie Ayaprun

Jones is a formidable force. More than 30 years ago, she pioneered

a bilingual, Yup'ik kindergarten program in Bethel, a hub for

the tundra villages that dot the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. Today,

the only Yup'ik immersion school in existence bears her name—an

honor she wryly acknowledges by saying, "The parent who suggested

it told me you don't have to be dead to have a building named

after you."

BETHEL,

Alaska— Though she stands barely five feet tall, Loddie Ayaprun

Jones is a formidable force. More than 30 years ago, she pioneered

a bilingual, Yup'ik kindergarten program in Bethel, a hub for

the tundra villages that dot the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. Today,

the only Yup'ik immersion school in existence bears her name—an

honor she wryly acknowledges by saying, "The parent who suggested

it told me you don't have to be dead to have a building named

after you."