|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

March 20, 2004 - Issue 109 |

||

|

|

||

|

A School Tries to Preserve the Native Tongues of Disenfranchised Baja California Residents |

||

|

by Enrique García Sánchez

- for the San Diego (CA)

Union-Tribune

|

||

|

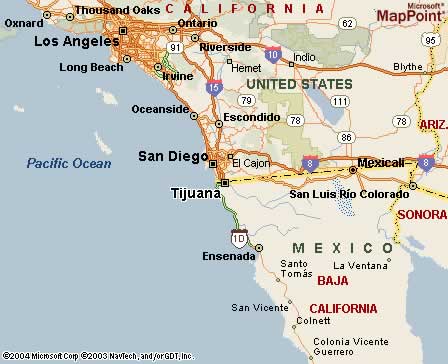

He recently learned to speak Spanish. David Maung

Some of her classmates teasingly call her oaxaqueña, which literally means from the state of Oaxaca, but is a condescending term Mexicans use to suggest a person is ignorant or lazy. She loses her smile, lowers her gaze and her voice fades to a whisper at the memory of these taunts. Nonetheless, this fifth-grade student at the Ve'E Saa Kua'a elementary school can feel secure because she lives in a community of 200 Mixtec families whose daily interactions strengthen their identity. Mixtecs are an indigenous people from the southwest part of Mexico. The name of the elementary school is in their language and means "House of Learning." The students there learn Spanish and several native languages. The school is one of the few public or private efforts in Baja California to try to preserve indigenous languages. There's no doubt that such efforts are needed, and not just for matters relating to language. Baja California's own native bands – the Kiliwa, Pai Pai, Kumeyaay and Cucapá – face the most critical situation in the state. Their numbers have dwindled, and they live in poor, isolated communities or have scattered into urban areas. They face the imminent disappearance of their native tongues, according to a state-sponsored conference held recently in Tijuana to mark International Day of the Native Tongue. Many of these tribes' traditions have been mainly handed down orally; keeping the language alive is the only way to preserve their history, customs and lore. One of the speakers at the forum said everyone has contributed to this problem, not just those in power. "We're always blaming (presidents George W.) Bush or (Vicente) Fox, but we lack a little self-criticism; this isn't the responsibility of the administration in power," declared sociologist Jorge Cocum Pech, president of the Academy of Writers in Native Tongues, a national organization formed a decade ago. He said that the distrust many indigenous communities feel of outsiders and their infrequent participation in projects to preserve their language and traditions are easily understood. "It's because we've been insulted and abused," said Cocum, recalling his years in grade school when he was punished for speaking his native tongue. In Baja California, no such prohibition ever existed for the large Mixtec community from the states of Guerrero and Oaxaca that have settled in the area since the 1950s. However, constant scorn has kept them from integrating into the state's society. Women who peddle arts and crafts on the street or beg are derogatorily called Marías, a term used for native women, and Mixtec men are called oaxaquitas, though most come from the southern state of Guerrero, not Oaxaca. More than 30 years ago the first group of Mixtecs settled in Tijuana, and about 15 years later the state created an indigenous education department to meet their needs. The first school to serve Mixtec students opened in Tijuana's working-class neighborhood of Colonia Obrera in 1982, recalled Tiburcio Castro, an education leader and current president of the Mixtec Language Academy in the Baja California-California region. One of those pioneering teachers is Gonzalo Montiel Aguirre, who 10 years ago became the founding principal of the Ve'E Saa Kua'a elementary school in Colonia Valle Verde, a settlement on the east side of Tijuana about 15 minutes from the Otay Mesa border crossing. Valle Verde was initially created as a resettlement zone for families left homeless by the floods of 1993. Currently, about 200 Mixtec families live there. The school serves some 500 students in each of its two shifts, about half of whom are Mixtec. The interaction between these children who are just learning Spanish and the non- indigenous students hasn't been without some friction, but Gonzalo Montiel maintains they have achieved positive results. "Our message has always been to promote understanding and respect for diversity." Two sons of Moisés Ramírez León are among the school's students. A native of Guerrero, he has lived in Tijuana for 13 years. He didn't finish grade school, but he's made sure that his children not only go to school but study both their native tongue and Spanish so they can fully participate in the socioeconomic life of the border, where sooner or later they also will have to learn English. "I don't want what happened to me to happen to them, I want them to learn Spanish but to keep speaking Mixtecan so they can communicate with their grandparents," he said. Promoting the use of native languages in family life and within the community was precisely the main recommendation made by the conference on native languages. Some of the projects planned for this year include a census of native-language speakers; creating a center for the study of the Purépecha, Náhuatl, Kumeyaay and Mixtec languages; and holding classes and workshops on literary creations in those languages. It's a race against time, warned sociologist Cocum Pech. "If we delay a little bit longer, we could find ourselves writing nothing more than the obituaries of these indigenous languages." Enrique García Sánchez contributes to the Union-Tribune's Spanish-language weekly, Enlace. |

|

|

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

TIJUANA

– At age 10, Alejandra Bartolo Ortigoza already knows what's

it like to be singled out because of her ethnicity.

TIJUANA

– At age 10, Alejandra Bartolo Ortigoza already knows what's

it like to be singled out because of her ethnicity.