|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

November 15, 2003 - Issue 100 |

||

|

|

||

|

Native Cure |

||

|

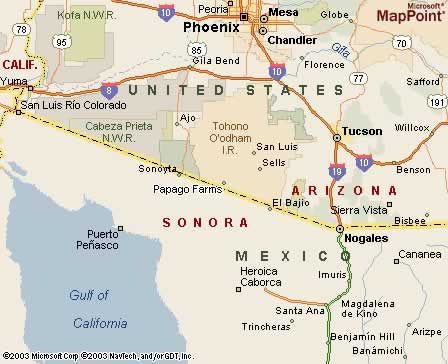

For this sliver of the 28,000-strong Tohono O'odham community, the first October harvest from this 18-acre farm 120 miles west of Tucson was more than a nostalgic return to a farming tradition that died out in the 1950s. It was a serious attempt to fight a modern scourge: diabetes. The group is part of a small but growing movement that believes traditional crops and desert plants contain substances that help regulate blood sugar and once protected them from diabetes. When the O'odham, formerly known as Papago, stopped eating these foods, members conclude, that protection was lost. The theory is far from accepted by the scientific and medical community, but it does reflect local frustration at conventional medicine in fighting the disease. "If we're ever going to win this diabetes, this sickness upon us, it's got to come from the heart, the faith that we have and our ancestors had," Christine Johnson said after she finished singing. The way to do that, said the rotund 63-year-old, was by "uniting with each other and going back to the foods that were helping before Bashas' opened up." Johnson doesn't have anything against the supermarket chain per se. Her complaint is more with federal government food and work policies after World War II that moved the tribe out of its farms and into cotton fields, ultimately fostering a dependence on government-supplied commodities, such as flour, sugar, lard and canned goods. "Now we go to Bashas' and get a hot dog. It's easier to do that than sweat and plant," said Johnson, who moves slowly and uses a walking stick. "I'm a diabetic, and this is what it has done to me." Today, more than 50 percent of Tohono O'odham adults have Type 2 diabetes, among the highest incidence in the world. People with diabetes can't produce enough insulin to properly regulate glucose, a basic fuel for cells. The glucose builds up in the blood and can damage the eyes, kidneys and heart. The chronic disease is linked to obesity, and scientists attribute the Native American diabetes epidemic to a modern diet high in fat and calories, a sedentary lifestyle and genetic factors. Desert

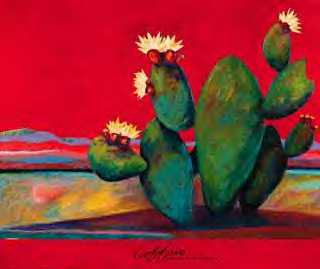

foods In the mid-1990s, Nabhan collaborated with nutritionists in Australia to publish several scientific papers stating that traditional desert foods, such as tepary beans, acorns and mesquite pods, contain a dietary fiber that reduces blood sugar levels or slows sugar absorption into the blood. What's more, he asserted, the mucilage, or gummy substance, that evolved to retain water in desert plants, such as cholla cactus buds and prickly pear fruit and pads, also serves to slow digestion and absorption of sugary foods. Offices of the American Diabetes Association in Tucson and Phoenix say they are not familiar with the research and are unable to comment. The Tohono O'odham initiative is part of a wider movement advocating a return to native foods. In Wisconsin, the Oneida Nation is trying to revive bison herds, while in Illinois, a Seneca leader is attempting to reintroduce Iroquois white corn, once a diet staple. Last November, the First Nations Development Institute, a 20-year-old Native American non-profit based in Fredericksburg, Va., held its first Native Food Summit in Albuquerque to discuss ways to boost local food production. It's also an approach that's bound to notions of cultural pride and identity. Besides chronic health problems, many Native communities suffer high levels of poverty, unemployment and violent crime. Food is one way of reviving community activities such as almost-extinct rainmaking ceremonies, harvest festivals and family meals. "We got to quit trying to live like other people," said Danny Lopez, 66, who teaches the Tohono O'odham language in the local community college and for years was a lone voice calling for cultural preservation. Founding

TOCA In 1930, said Tristan Reader, a community activist, the tribe produced 1.6 million pounds of tepary beans. In 2003, you'd probably get to eat tepary beans only if you had a grandmother on the reservation who cooked when you visited, using produce from her own garden. In 1996, Reader, who is White, and O'odham basket-weaver Terrol Dew Johnson founded Tohono O'odham Community Action to preserve O'odham culture and to revive traditional foods. So far, TOCA has helped about 100 families start small vegetable and fruit gardens, though it's unclear if the families have kept up the plots. The Papago Farms project is its biggest to date. Terrol Dew Johnson, a relative of Christine Johnson, has seen diabetes ravage his family. His maternal grandparents were both diagnosed in their 80s, and his grandfather died of complications from diabetes two years ago. His parents, who ate more of a "meat, potatoes and white bread" diet, were diagnosed with the disease in their 50s, he said. Johnson himself is 30 and was diagnosed with diabetes five years ago. He's 6 feet 2 and weighs 283 pounds. His doctor said he should weigh between 240 and 250 pounds. "With the lifestyle I live now, it's impossible" to eat traditional foods, he said over lunch of greasy fry bread topped with chili and washed down with Diet Pepsi. "Well, not impossible, but inconvenient, I guess." Genetic

research For 40 years, the National Institutes of Health has studied the neighboring Gila River Indian Community, whose diabetes rates are on a par with those of the Tohono O'odham. That path-breaking research linked diabetes with Chromosome 1Q, a linkage that has since been replicated in other groups, including the French, English, Amish, Japanese and Chinese. But what the NIH research has yet to produce is a cure. This month, an international consortium will send DNA samples to the Sanger Institute in London to be sequenced to try to identify the specific gene linked to diabetes. It's a potentially pivotal moment in diabetes research. Even if they succeed, "there's no guarantee that what we learn will ever change anything or lead to therapies," said principal investigator Nancy Cox of the University of Chicago. Clifton Bogardus, chief of NIH's Phoenix research branch, said he understands the local frustration. "They see a lot of people dying, hundreds of people on (kidney) dialysis," he said. Bogardus is skeptical that native foods contain substances that can prevent diabetes. "Anything is possible," he said, but called it "highly unlikely." "What is very likely is that if you had to live off this environment and food of the desert, you would be pretty skinny and wouldn't have diabetes." The scientific divide leaves Arizona tribes to figure out who and what to believe. Even as the Tohono O'odham are trying to restart community agriculture, the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community pledged $5 million in June to Phoenix-based Translational Genomics Research Institute, specifically for research into diabetes. The Gila River Indian Community, which has been the subject of decades of NIH study, is building a diabetes medical center and emphasizing exercise programs in schools. NIH research has helped to secure federal funding for diabetes prevention and education programs, said the tribe's lieutenant governor, Mary Thomas. Asked what she thinks of the traditional diet advocates, she answered with a question: Given a choice between a "plate of Indian beans and a Big Mac staring at you, which one would you choose?" |

|

|

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

PAPAGO

FARMS, Tohono O'odham Reservation - A gray-haired woman stood

by a trailer piled high with watermelon, squash and cantaloupe

and sang harvest songs from her childhood. About 60 people savored

traditional dishes of roasted corn gruel, sautéed cholla

buds and beef stewed with tepary beans. They drank mesquite juice

and lemonade flavored with prickly pear fruit.

PAPAGO

FARMS, Tohono O'odham Reservation - A gray-haired woman stood

by a trailer piled high with watermelon, squash and cantaloupe

and sang harvest songs from her childhood. About 60 people savored

traditional dishes of roasted corn gruel, sautéed cholla

buds and beef stewed with tepary beans. They drank mesquite juice

and lemonade flavored with prickly pear fruit.