|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

November 15, 2003 - Issue 100 |

||

|

|

||

|

Keeping Their Word |

||

|

by Andrew Metz Newsday

|

||

|

credits: Alejandra

Villa/Newsday

|

|

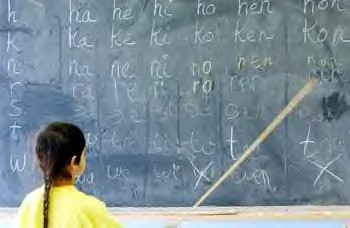

And though the 64 students at the Akwesasne Freedom School learn math and history and reading, their real purpose is their people's cultural survival. "My grandmothers and aunts got spanked if they talked Mohawk at school. That's how we lost our language," said a 12-year-old pupil, whose name is a thicket of letters -- Tehrenhniserakhas, pronounced De Lon Ni Zeh Lakas -- that means "He Puts Two Days into One." "Now we have a better sense of our language than probably any other kids." In a last chance to reverse the consequences of American policies that sought to obliterate Indian identity, the school is immersing children in traditional language and customs and counting on them to emerge the faithkeepers of the new century. With most fluent speakers in their twilight years and few families maintaining Mohawk traditions at home, the intensive teaching on this reservation that spreads over the Canadian border begins before kindergarten and concludes at eighth grade. Mohawk is the only language allowed except for the final two years, during a crash catch-up in English to prepare for public school. "We saw what happened to one generation that lost their culture, lost their history, lost their language," said Sheree Bonaparte, Tehrenhniserakhas's mother, who 25 years ago was one of the first teachers at the school -- the forerunner to immersion programs that have been blossoming around the country. "We decided that we didn't want to raise American children or Canadian children. We wanted to raise Mohawk children." Out of the limelight, these schools -- as many as 50 nationwide -- have become vanguards of a dramatic change in Indian education building since the 1970s, when U.S. officials and Indians began trying to redress a history of forced assimilation dating to the 19th century. Where Indian children were once shipped to federal boarding institutions to be purged of their native ways, schools around the country are now steeped in tribal history and heritage. "Our generation, we were punished for speaking Mohawk. Now we are getting paid to teach it," Lillian Delormier, a third- and fourth-grade teacher, said with amusement, as she watched her students race around the playground, their language flying like sparks through the air. "When I was brought up, all this was a no-no." The linguistic revival is at the core of broad efforts by Indian people to uplift their communities, yet it is also an act of desperation, as native languages are vanishing and taking with them irreplaceable traditions. By 1900, amid the boarding school era, only about 400 Indian languages were in use on the continent. Today, there are around 185, most precariously close to extinction. Linguists and Indian educators predict that many will vanish in less than 50 years. "The tribal languages are the libraries of information for each tribe. They contain the genesis, the cosmology, all the oral histories," said Darrell Kipp, a leader in the immersion movement and founder of the Piegan Institute, a center on his Blackfeet reservation in Montana dedicated to preserving native languages. "They are a blueprint for how to look at the world."

"This is a survival school. I want to survive as a Seneca for a little while longer," said Dar Dowdy, who six years ago founded the Seneca's Faithkeeper's School. "Our old people tell us that when you lose your language, you're nothing, you're just a social security number." The immersion programs, most of which are privately or tribally funded, are considered by many experts the surest way to stem the onslaught of cultural illiteracy, imparting an Indian perspective on everything from geography to botany. Because of this intense focus, students can be set back in mainstream subjects, particularly English, when they enter public schools. But after some quick catch-up they usually excel: four of the five Indians inducted into the National Honor Society in the local high school last year had attended the Freedom School. "It may take us a couple of weeks to catch up to their work at the beginning of the year," said Tsiehente, (pronounced Jeh Hon Deh) Herne, 13, an eighth-grader. "But after that we zoom past them." The schools also lure parents back to the classroom to reclaim their complex native tongue. The Mohawk language has similar cadences to English but uses only 11 of the 26 letters of the English alphabet. Its vocabulary is florid, atavistic and evolving in real time to incorporate the modern world. "Out of everything I learned at Cornell, nothing compares to this, maybe neurology," said Iotenerahtatenion, (pronounced Yo De Neh La Da Den Yo) Arquette, an environmental researcher and veterinarian, who is one of about 20 mothers studying in the Freedom School's adult program. The language renewal push is also permeating public schools that serve most native children, even as educators continue to contend with deficiencies in mainstream Indian education. Federally funded schools and public districts are now routinely incorporating native language and traditions into their curricula. The U.S. Department of Education and the Bureau of Indian Affairs are spending tens of millions of dollars on improving student performance and training teachers. On the Canadian side of this reservation, one elementary school offers immersion from pre-kindergarten to sixth grade. "Every single book, every single resource material we have to make for ourselves," said Margaret Cook-Peters, who develops Mohawk studies at the Akwesasne Board of Education. New York's Salmon River School District offers language and culture at both its high school and elementary levels and has recently started an advanced Mohawk class. The district is also running a summer program for teachers around the state on Iroqouis history. In the district's St. Regis Mohawk primary school – entirely Indian, 452 students, pre-kindergarten to sixth grade – there is a distinctly native aesthetic, from a mosaic at the entrance depicting the Mohawk creation story to murals in the cafeteria of the clan system. Still, administrators and teachers acknowledge that the Mohawk classes held every other day at best can open students' eyes. "In this situation and this setting I can't take a non-native speaker and make them a speaker," said Irving Papineau, the principal, a graduate of the school. "My primary responsibility is to make sure they meet their academic standards. We've got our hands full." At the Freedom School, there is no such calculation. Mohawk is first, from the moment the students flop onto benches at 9 a.m. Quiet envelops the hall, then the young Indians together welcome the day with the "Words Before All Else," an homage to the natural world meant to bring their minds into focus as one. "There was a process to get rid of us, but it didn't work," Elvera Sergeant, the school manager, said as another day commenced and students scattered to their classes. "This is where you learn where you came from and who you are." |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

Akwesasne

Mohawk Territory, N.Y. -- There's a small school in the far north

of New York where English is a foreign language. The tongue taught

here is Mohawk.

Akwesasne

Mohawk Territory, N.Y. -- There's a small school in the far north

of New York where English is a foreign language. The tongue taught

here is Mohawk.  The

Mohawks may be in better shape than other New York tribes, with

as many as 2,000 to 3,000 speakers out of roughly 12,000 on the

reservation. The Senecas, however, estimate that fewer than 100

people are fluent, while other members of the Iroquois Confederacy,

such as the Oneidas and Onondagas, have hardly anyone able to converse.

The

Mohawks may be in better shape than other New York tribes, with

as many as 2,000 to 3,000 speakers out of roughly 12,000 on the

reservation. The Senecas, however, estimate that fewer than 100

people are fluent, while other members of the Iroquois Confederacy,

such as the Oneidas and Onondagas, have hardly anyone able to converse.