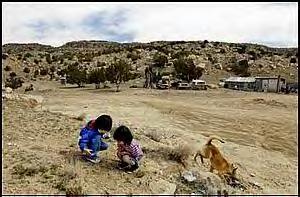

MANUELITO,

N.M. -- Here's Sierra Chopito with the vast, gritty horizon of juniper

and sage and sandstone of the Navajo Nation spread out before her, fixated

on a sprinkle of tiny buds like snowflakes on a patch of hard ground. MANUELITO,

N.M. -- Here's Sierra Chopito with the vast, gritty horizon of juniper

and sage and sandstone of the Navajo Nation spread out before her, fixated

on a sprinkle of tiny buds like snowflakes on a patch of hard ground.

Not for long, of course.

The cousins are here and so are

aunts and uncles and elders, come to see each other and her great-grandfather,

who at 77 still herds his flock of 60 sheep and goats each day through

the craggy hills of the family's isolated stretch of reservation land

15 miles west of Gallup, N.M.

Sierra, 4, is a favorite when she

comes to visit this rustic family homestead where all but one particle-boarded

home has no electricity, no running water and where outhouses are still

often the only form of waste management.

"Sierra attracts people to

her," said her mother, Ethel Ellison. "She is a bright star."

Brighter than most children her

age in McKinley County, the poorest county in New Mexico and the third

poorest in the nation. Nearly three out of four children in Gallup-McKinley

County Public Schools receive free or reduced lunch. Most children entering

kindergarten are two years below their expected developmental levels.

But within this impoverishment

lays the great richness of Sierra's Navajo and Zuni cultures and a family

determined to teach it all to her.

As it turns out, the traditional

way — the Beauty Way, as they call it — is good science. Nurture,

teach, stimulate the whole child before birth and through the early years

and the brain wires and weaves itself like the finest Navajo rug.

Ellison, 36, learned the importance

of that by reading college textbooks and by sitting at her grandmother's

knee.

"The way I picture my grandmother

... now is her sitting under the tree with children all around her,"

said Ellison, a parent educator who teaches other parents early childhood

skills. "That was her happiest moment. She was in tune with the children.

She spent a lot of time with them, playing, talking to them. She didn't

know at the time that was how they were learning."

Even while still in the womb, Sierra's

brain was already weaving. Ellison said she spoke often to her unborn

child both in English and Navajo. She played soothing cassette tapes of

traditional Indian songs and Dr. Seuss ABCs.

When she was seven months pregnant,

Ellison stayed in her grandfather's house, a one-room, six-sided ceremonial

structure — with a medicine man who prayed and sang over the baby

in her womb for four straight days, setting in motion the tangled tapestry

of neurons in Sierra's brain and starting her on the path of the Beauty

Way.

Sierra, named for her mother's

vision of green mountains during the throes of contractions, was Ellison's

and Wayne Chopito's second child, coming five years after brother, Nolan.

She

is a child on the move, kinetic like her whirlwind of thick black hair

that never seems completely tamed. She

is a child on the move, kinetic like her whirlwind of thick black hair

that never seems completely tamed.

"I am ready to work now,"

she tells her mother during a recent car ride through town. Ellison hands

her a clipboard with coloring sheets. That's good for a few minutes, but

now it's on to a picture book where Sierra deftly points out all sorts

of creatures she has likely never seen anywhere but on a page.

"This is a crab," she

said.

Sierra's round brown eyes zoom

in on a school bus driving by.

"That's a bus," she shouts.

"What kind of bus?" Ellison

asks. "Is it a big bus? Is it a yellow bus?"

Ellison and Chopito, also 36, continuously

engage Sierra in conversations like this, their words like raindrops in

the 50,000 nerve arroyos that carry sound to Sierra's brain.

"It's important that we keep

talking," Ellison said. "I've talked to her even before she

was born."

Words, sounds, sights, smells,

her family's positive and frequent interactions sparked trillions of brain

connections, called synapses, to form at an astounding rate of 3 billion

a second by the time Sierra was 8 months old.

Because of the attention she received

in her earliest years, her brain is well-woven with such synapses, assuring

her at least the increased potential for a higher IQ and well-being —

all without benefit of financial status or federal assistance.

"You don't have to be rich

to give good modeling," Ellison said.

Sierra's first two years were lived

in low-income housing in Gallup while Ellison studied for her teaching

degree and Chopito worked construction.

By 2, Sierra was trying to read.

"I read 'The Very Hungry Caterpillar'

so much to her when she was littler that she had it memorized and tried

to read it herself," her mother said.

After

Ellison graduated, the family squeezed into a tiny two-bedroom duplex

perched on a ragged red bluff in the heart of town where trains wail and

rattle by at all hours and quick-pay loan companies clutter like beer

cans along the historic stretch of nearby Route 66, Gallup's main drag. After

Ellison graduated, the family squeezed into a tiny two-bedroom duplex

perched on a ragged red bluff in the heart of town where trains wail and

rattle by at all hours and quick-pay loan companies clutter like beer

cans along the historic stretch of nearby Route 66, Gallup's main drag.

Inside, though, there is warmth

and love and learning. Mother and daughter sprawl on the floor playing

with a small cast-iron stove. It's a clearance sale purchase from the

local Cracker Barrel and one of the legs is hanging on with glue, but

it's just fine for make-believe.

"I'm making corn," Sierra

announces as she scoops air from a tiny pan.

"How about some tortillas,

too?" her Mom asks.

Sierra moves on to stringing jeweled-colored

beads. Her Mom asks her to count them. Sierra makes it to 15.

"That's very good," her

Mom says. "Now can you count in Navajo?"

Sierra needs a little help but

she does it, her tongue deftly clicking in the cadence of the Navajo.

Later, Daddy and daughter will

share their nightly bowl of rocky road ice cream and Mom will read to

Sierra like always.

"I like to get them books

instead of toys," she said. "You can always make toys out of

mud and sticks or cardboard boxes."

That is what Ellison did as a child

on the reservation where "Sesame Street" and Gameboys were things

she only imagined, if she thought of them at all.

"It's a child's paradise,

if you think about it," she said of the rough-hewn land. "Like

an endless playground."

And so she takes Sierra back there

weekends, spring breaks, summers. Someday soon, maybe next year, Ellison

will ask to begin her own family's home site on an acre of her grandfather's

land.

Her grandmother, the heart and

mind of the clan, is gone now, passed on since January.

"She's in spirit," Sierra

explains with a worldly voice.

She's also in Sierra, weaving.

|

![]()

MANUELITO,

N.M. -- Here's Sierra Chopito with the vast, gritty horizon of juniper

and sage and sandstone of the Navajo Nation spread out before her, fixated

on a sprinkle of tiny buds like snowflakes on a patch of hard ground.

MANUELITO,

N.M. -- Here's Sierra Chopito with the vast, gritty horizon of juniper

and sage and sandstone of the Navajo Nation spread out before her, fixated

on a sprinkle of tiny buds like snowflakes on a patch of hard ground.

She

is a child on the move, kinetic like her whirlwind of thick black hair

that never seems completely tamed.

She

is a child on the move, kinetic like her whirlwind of thick black hair

that never seems completely tamed.  After

Ellison graduated, the family squeezed into a tiny two-bedroom duplex

perched on a ragged red bluff in the heart of town where trains wail and

rattle by at all hours and quick-pay loan companies clutter like beer

cans along the historic stretch of nearby Route 66, Gallup's main drag.

After

Ellison graduated, the family squeezed into a tiny two-bedroom duplex

perched on a ragged red bluff in the heart of town where trains wail and

rattle by at all hours and quick-pay loan companies clutter like beer

cans along the historic stretch of nearby Route 66, Gallup's main drag.