|

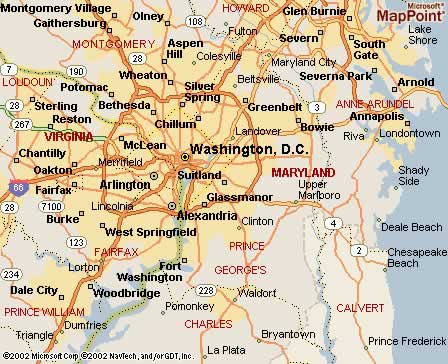

SUITLAND,

Md. -- George Gustav Heye, a wealthy New Yorker born in 1874, was a compulsive

collector of Native American artifacts. He would visit Indian reservations

and be anxious and irritable until he'd bought everything in sight. He

sponsored digs. He bought out other collectors. By the time he died, his

collection had grown to 800,000 items. SUITLAND,

Md. -- George Gustav Heye, a wealthy New Yorker born in 1874, was a compulsive

collector of Native American artifacts. He would visit Indian reservations

and be anxious and irritable until he'd bought everything in sight. He

sponsored digs. He bought out other collectors. By the time he died, his

collection had grown to 800,000 items.

Some

people who knew him said he didn't seem to care about individual Indians

or about keeping their cultures alive.

"George

didn't buy Indian stuff in order to study the life of a people, because

it never crossed his mind that that's what they were," an anthropologist

who worked with him told a New Yorker reporter in 1960. "He bought

all those objects solely in order to own them."

There

were other sides to Heye. Some people credit him with ending a drought

in North Dakota by returning a sacred rainmaking bundle to the Hidatsa

Indians.

"I

think he did go beyond just hoarding things," said Thomas Sweeney,

spokesman for the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian.

It's

hard to imagine, though, that he could have seen in his collection what

Teri Rofkar saw.

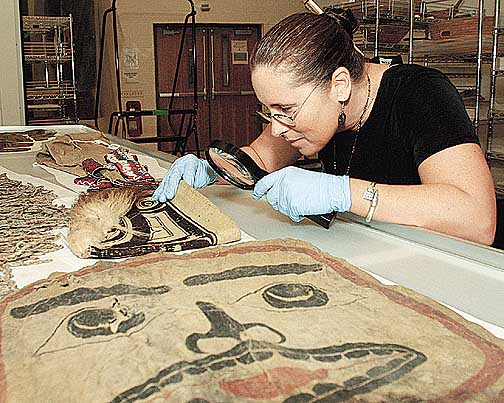

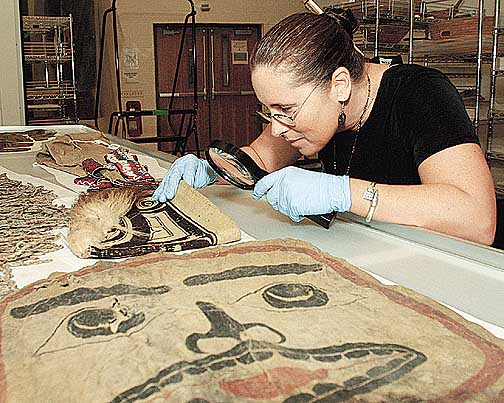

Rofkar,

an Alaska Native weaver from Sitka, recently picked through the Tlingit

portion of his collection as a visiting scholar at the National Museum

of the American Indian, which now owns Heye's trove.

Amid

hundreds of things carved, sewn and woven by her forebears, Rofkar had

an easy familiarity, as though decades and centuries did not stand between

her and the people who made and used them.

"Good-looking

pants!" she said, eyeing a slender pair of red-trimmed leather leggings

lying flat in a drawer. "He would have been HOT stuff."

She

lifted old baskets off their shelves and examined them, sometimes with

a magnifying glass, to learn the techniques of long-dead weavers.

"How

many free rows did she get? Four, and then she started to add warp,"

she said, looking over one specimen.

Heye's

collection will be the cornerstone of the National Museum of the American

Indian when it opens near the Capitol next year. Much of it is and will

remain housed in a Smithsonian facility in Suitland, just outside of Washington,

D.C. Heye's

collection will be the cornerstone of the National Museum of the American

Indian when it opens near the Capitol next year. Much of it is and will

remain housed in a Smithsonian facility in Suitland, just outside of Washington,

D.C.

The

collection's new keepers say they don't want to keep it locked away. They've

been opening the doors at Suitland so Native Americans can reconnect to

the things their cultures produced.

The

scholarship they gave Rofkar, which included tours of other East Coast

museums, is part of that effort.

Rofkar,

46, weaves both baskets and textiles, having learned as a child from her

grandmother. She teaches others to weave, mostly in Southeast Alaska.

She's

excited by what she sees as a renaissance in weaving on the Northwest

Coast.

"There's

getting to be more and more of us," she said.

Dwarfed

by the 12-foot-high metal stacks in the Suitland building, she opened

a yard-wide drawer to find a score of baskets, some of them hundreds of

years old.

She

allowed herself to ooh and ah a little, but she said she tried to keep

her awe in check.

"You

can't let it overwhelm you, because then you can't develop a relationship,"

she said.

So

she dug right in, basket by basket.

She

ticked off the designs she recognized -- wave, tides, shaman's hat, Raven's

hood, porpoise board.

Some

of the baskets employed the same techniques that she learned from her

grandmother and that Rofkar passed on to her own daughter.

But

over and over again, Rofkar saw one complicated striped pattern she didn't

know and didn't even know what to call.

"No

one on the coast is doing it anymore," she said.

She

hopes a better name will suggest itself, but she came to think of it as

"candy stripe."

Sitting

with one of the old baskets and her own weaving materials, she figured

it out. Now she hopes to teach it to others.

Heye

kept little or no information about the weavers when he collected his

things, but Rofkar recognized some of them by their work.

"I

think this gal has a piece in the Sheldon Jackson Museum," she said,

holding one little basket.

Another

weaver impressed her with spruce root cut so finely it looked as though

the basket were woven of thread. Rofkar turned the basket over and pointed

out that the weaver had started out with thicker warp and weft.

"Just

before she went up the side, she split everything down, and once again,"

Rofkar noted.

One

drawer she opened was full of rattle-tops, baskets with small clattering

bits woven into a chamber in the lid.

She

lifted and shook. Some held stones. One clinked with metal shot.

In

one of the long drawers she found a delicate woven teapot, just a few

inches high. In

one of the long drawers she found a delicate woven teapot, just a few

inches high.

Her

grandmother, Eliza Mork, used to make teapots and little cups, Rofkar

said.

Rofkar

said she used to think her grandmother's teacups were too touristy, not

fitting projects for such a talented weaver.

But

they meant something to her grandmother. When Mork was a girl, in the

early 1900s, Sitka was a segregated town. Her grandmother said she could

see that on the other side, little white girls had tea parties with little

china teacups.

"Gram

said she would go home and just cry and cry," Rofkar said.

Decades

later, Mork retained an affection for the little teacups she wove for

sale.

After

Suitland, Rofkar visited other East Coast museums. At the University of

Pennsylvania she saw 16 baskets from her clan, Ta'kdeintaan, of Hoonah.

"Some

of them were probably my grandma's and my great-grandma's," she said.

"I recognized the patterns, and there was continuity of the styles."

There

she also finally saw the Lituya Bay robe, which she had recreated based

only on a written description. The weaving took her 800 hours.

"I

tried to keep my cool, but that was just -- Oh my god," she said.

Reporter

Liz Ruskin can be reached at 1-202-383-0007 or lruskinadn.com

|

![]()

SUITLAND,

Md. -- George Gustav Heye, a wealthy New Yorker born in 1874, was a compulsive

collector of Native American artifacts. He would visit Indian reservations

and be anxious and irritable until he'd bought everything in sight. He

sponsored digs. He bought out other collectors. By the time he died, his

collection had grown to 800,000 items.

SUITLAND,

Md. -- George Gustav Heye, a wealthy New Yorker born in 1874, was a compulsive

collector of Native American artifacts. He would visit Indian reservations

and be anxious and irritable until he'd bought everything in sight. He

sponsored digs. He bought out other collectors. By the time he died, his

collection had grown to 800,000 items. Heye's

collection will be the cornerstone of the National Museum of the American

Indian when it opens near the Capitol next year. Much of it is and will

remain housed in a Smithsonian facility in Suitland, just outside of Washington,

D.C.

Heye's

collection will be the cornerstone of the National Museum of the American

Indian when it opens near the Capitol next year. Much of it is and will

remain housed in a Smithsonian facility in Suitland, just outside of Washington,

D.C. In

one of the long drawers she found a delicate woven teapot, just a few

inches high.

In

one of the long drawers she found a delicate woven teapot, just a few

inches high.