|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

February 8, 2003 - Issue 80 |

||

|

|

||

|

Dairy of C. H. Cooke on a Canoe Trip up the Chippewa River in the Spring of 1868 |

||

|

From: Eau Claire Telegram September

30, 1917

(Second of Four Installments) |

||

|

Note - The diary

kept by C.H. Cooke of Mondovi during a canoe trip made by himself, George

Sutherland, and Captain Shadrach A. Hall, principle of the Old Eau Claire

Wesleyan Academy, up the Chippewa River in the spring of 1868, gives

a detailed picture of valley and its life at that period not duplicated

by other writing known to exist. The third installment will appear soon.

|

||

|

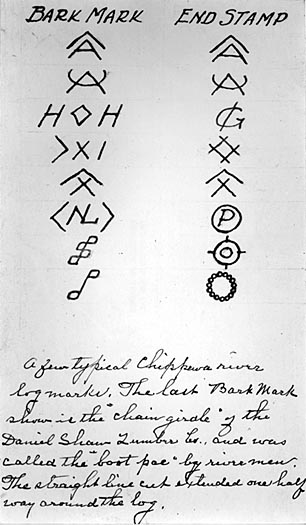

Photo

1: Chippewa River Log Marks; |

||

|

April 24 - All aboard for the upper Chippewa: snow, which had been falling intermittently the two night past, had melted and the troublesome logs having dwindled to a thin stream we had no excuse to longer delay our going. The professor was insistent, and the news we gathered from some dozen log drivers, that the river above the falls was quite free from logs, decided us to renew our trip. Bidding our friend Brunet and his family good bye immediately after dinner, we at once commenced the portage of the falls with our canoe and its contents. It was no child's play to pack the contents of our canoe, our camp equipage, guns, paddles, blankets, tents and cooking outfit near a quarter of a mile, from the boat landing below Brunet Falls to the nearest safe landing above the falls and on top of all we carried the canoe, with a deal of sweating, sprawling and many stops. At the worst places calling for patience and extra nerve, George would think 'darn it,' the professor would hum a Methodist hymn and I would do the cussing. To a lover of the romantic, of the wild and picturesque, the scene about the falls is most satisfying. The terrific rush of water through the rocky channel, the seething, foaming flood expanding into a broad, placid river below the falls, and the deep green of the eternal pines that crowd the river's shore, as if they wanted to see their reflected forms in the depths, combine to fill one with a sense of the strange and beautiful. Near

Disaster

It was mid-afternoon when we finally got started. Meeting a bateau of 'sackers' belonging to Daniel Shaw's company they cheered us up a bit by telling us that the tail end of the drive was just a little ways above. (Note - The 'sackers' are those whose work is to roll stranded logs out into the current.) There was little to vary the scene of the afternoon, of winding river and unbroken forest. What seemed a little strange, saved the cleared face of some high bank to serve as a roll away, there seemed to be no shopping along the riverbank. It was a constant wonder to us where the logs came from. The riverbank for the most part was as wild and virgin as if it had never known the presence of the destroying white man, but these high banks and tributary streams with there endless flow of great beautiful timber told but too plainly of his destroying presence; and the murmur of the pine tree tops when ever the winds touch them ever so gently had a somber note of complaint, as if the spirit of the forest foreboded some strange disaster. Select

Camp Site At last we came to what seemed a pretty spot for a camp just as the last gleams of the sum was gilding the tops of the new lordly pine that seemed to over top their fellows. We pitched our tents on a high bank, covered with a carpet of pine needles, the foliage of years. It was a solitary spot. The cry of some waterfowl back from the river touched us with a hunter's itch. The professor called my attention to a smooth worn slide from a twenty-foot bank into the river. He did not guess it but I did, it was a playground for the otter. I had seen many of them on the Beef River in Buffalo County and on its supplying streams. I knew their tracks very well. At our evening meal, which George, chief cook, provided, we melted into the form of syrup, some of the sugar, which I had two days before purchased from the Indian woman below Brunet Falls. It was really good. I ate of it until the professor protesting made me ashamed. During the night we heard the honk of geese and swans and the strangely human cry of the loons. Whenever a loon would cry I would punch George in the ribs and ask him if he wasn't afraid. I can think of nothing more solitary, more woe bygone, in the silence of the deep forest than the cry of a loon away back somewhere. I would tell George that I heard a panther's cry. After listening for a while he would say, "Oh, it's nothing but a couple of loons talking over some domestic differences." April 25 - The morning broke, as the professor put it, "clear and beautiful as the morning of the first creation, when everything was new." When I opened my eyes he was standing with arms folded, looking out upon the river and exclaiming "My is not this glorious?" There was little sound of animal life save an occasional barking of a chipmunk or the cry of passing ducks. The river swollen with yellow water and freighted with debris of logs, never stopping glided on and on. After swallowing our breakfast or rather hard biscuits, given us by the Brunet girls, and some strong coffee, sans milk or cream, and leaving the Professor to clean up things. George and I took our guns and struck back in the woods to find where the cry of the ducks came from that we had been hearing. A half-mile brought us to the marshy shore of a small lake. Near its center we spied two swans and all about them were a lot of ducks and loons. At no point could we reach them from shore. On our return George bagged a partridge, the only other game we saw. We came onto a neck of water that seemed to connect the lake with the river. We found some teepees here where the Chippewas evidently had camped either to hunt or to make sugar from the maple trees. Guided

by Indian The day's work ahead proved the hardest yet. We were compelled to make two portages before night on account of rapids, in one case carrying our canoe and stuff near quarter of a mile. In this place we had the help of an Indian. He guided us the best route through the timber. We rewarded him with a steel trap and a calico handkerchief, which pleased him. The Indians as we were coming to know are distrustful of white man's promises. This man consented to help only after a good deal of parleying. In the afternoon the professor, who was hunting along the shore, lost his revolver, in attempting to save himself from a wetting in crossing some loose logs. I say lost, I should have said lost for a time. After two hours fishing about we found it again. We had planned in the morning to make the mouth of the Jump River, but we were so harried with first one thing and then another that we went into camp some three miles below the mouth of the Jump. The professor who hunted the west shore came into camp with two squirrels, which with the partridge George shot in the morning made a tasty supper and breakfast. The

Professor Gets a Dunking

The rat was struggling in the water some 20 feet from shore among some logs. Dropping his gun he ran out upon the logs and just as he was reaching for the rat the log turned and in he went. George and I were looking on and both of us started down the bank in wild haste to the rescue, but the water was only shoulder deep and the professor told us to stay away lest we should get a wetting too. Of course the laugh went around, the professor joining in a grim sort of way. As the professor had had the first dunking we felt sorry down in our boots that it had not been either George or myself. The truth is that the professor has a sort of dignity about him, which rather forbade us laughing real heartily at his mishaps. I would have enjoyed it more if it had been myself. He got the rat all right and I skinned it and stretched the skin on a willow bough, just as the Sioux Indians taught me to do away back even before my teens. The brush fire we built to dry the professor stripped to drawers and shirttail, lighted up the dark forest for some rods about us. The bird tribe of all sorts during the day were wild and very scarce. A few cranes and ducks were seen but they flew high.

Indians Offer Sugar April 26 - The professor beat us up by an hour and a half, and after frying the squirrels and making coffee called George and me to breakfast. The world never seemed so beautiful, in fact everything about us seemed made for our special enjoyment. While at breakfast four canoes of Indians came paddling down river. One of the canoes landed and offered us maple sugar, while the other three floated on. To my disgust and to George's the professor waved them off telling them we had plenty of sugar. I wanted to talk to them but as they were repelled by the professor, they pulled away from the bank. The squaws, who did the paddling, set up a cry of complaint, as if reproaching the men, who sat quietly holding their guns. What they meant of course we could not guess, though we wished ever so much that we could. We were soon afloat and finding the current less swift made good progress. I took to shore a part of the time until we landed for noon. The scarcity of animal life is a continual surprise. A saw a few deer tracks but no deer. We did not care to see any deer, as we knew they must be poor. It seemed very strange that in the forest so deep and apparently unvisited by man there should be such a scarcity of animal life. Meet

Daniel Shaw We passed the rear guard of the Daniel Shaw Lumber Company drive this afternoon. Before we came to them, we had for some time been hearing human voices away up beyond the dark shady bends in the river. We were hugging the shore to avoid the logs when George, who tramping the west side, called me to land. I was a bit surprised on landing to find him in conversation with Daniel Shaw of Eau Claire. I had been given a letter to Daniel Shaw by Frank Moore, to deliver to Mr. Shaw when we should meet his drive. Mr. Shaw was cooly sitting upon a fallen log nor did he move save to reach out his hand when I game him his letter. He merely asked in a quiet tone if I knew the 'import' of the letter. My answer was that I did not, except that there seemed to be trouble between the Beef Slough people and the Eau Claire mill men, about the holding of logs. After reading the letter, he said my suspicions were right, that the letter related to those matters. One curious thing about Shaw that we had often heard was, that unlike other Chippewa mill men, he always went in person to see about the driving of his logs. When we went back to our canoe Sutherland quoted something about "Marius sitting alone on the fallen column mediating on the fortunes of the Roman Empire." Our

stock of provisions ware getting low and if we reach the Flambeau, as

we hope sometime tomorrow all will be well. Lumbermen's

War April 27 - This morning dawned cool and clear. We were glad to gather close to the fire and to warm our most freezing fingers, after an hour of patching and cussing in the water repairing our shattered and battered craft. We hugged each other under the blankets last night to keep warm. We did not strike camp until afternoon today. The Beef Slough logs, driven by a lot of piratical fellows, gave us something to think about. It looks as if there was a war on between the Chippewa people and the Beef Slough crowd, the latter headed by James Bacon, the spokesman and manager for Palmer of Michigan. My sympathies are rather with Beef Slough, but I wish the Beef Slough drivers were a little more decent. April 28 - A four-mile journey brought us to camp for the night. It looks as if we were getting reckless of time and events. At the end of two miles on seeing what looked like an Indian camp we landed and walked to the nearest hut, opened the canvas door and entered. George and I were alone. As sure as I live, the only creature in the hut, save a couple of snarling dogs, was a pretty girl, handsome as Pocahontas, of about my age. Well, as I told George I never felt so romantic in all my unromantic life. I wanted to surrender at once, but George, being less impressionable said, "Lets go back to the canoe." It was a queer abode. I tried to say something apologetic to this mute American maid, but the Babel affair with its confusion of tongues, made our best efforts ridiculous. The coming of the professor, who had become impatient, broke the spell and we returned to the canoe. I do not know what thoughts George had about this rude native hut and its inmate, but I imagine he was as content to have his thoughts remain secret, as I too was content to have mine. I should perhaps add in perfect frankness, that while George regarded all mankind as in spiritual relationship, the peculiar unhappiness of the darker races, due to the greed or negligence of the superior white race, gave him no special concern. The river was less rapid and our progress more rapid. We had a fairly good day without special event. Best of all we had no cataracts to carry our boat and goods around. Yesterday we made three such portages. Several Indian camps and a few French huts gave variety and interest to the day's doings. We traded for some sugar with the Indians and bought some bread from a French settler. Frenchman

and Squaw We found a very old Frenchman and his Chippewa wife in one of the Indian teepees. A younger woman, a half-breed, a really fine looking woman, in the same tent, was his daughter. Her husband was a full-blooded Chippewa Indian. The half-breed, we have noted, are superior looking people. This old Frenchman had been on the Chippewa for nearly a half century trading in furs and mingling with the Indians. He was sorry to see the coming of the whites, who he said spoiling the Indians and wronging their women. About sunset we reached the mouth of the Flambeau River. Our crackers being scarce and bread difficult to get, we shall try and lay in a stock before leaving. At sunrise we were again aboard our frail bark boat and headed up the now smaller Chippewa River. We were now above the Flambeau River, or as the Indians call it, the Manidowish River. Its relationship to the Chippewa River is like that of the Missouri River to the Mississippi, that is, it is the larger stream. Our sailing during the forenoon was favored by still water. I shot a duck just before getting into camp, the one shot out of many shots that counted. We cannot understand why ducks so wild away up here on this lone river. They fly most of them above the tops of the trees and that is beyond the reach of guns. Indians

Shrewd Traders

"They

live in the past that is misty and dim We saw three river men today, and they floating down river in a bateau. They told us that nearly all the logs had passed down and our way above would be clear. Our camp for the night was pitched on a high dry point or peninsula jutting into the river and lorded over the monarch pine that might have been centuries old when Columbus came. Ash piles, about the point and remains of teepee poles in all stages of decay hinted at successive races of red men had come and gone. The day's adventures and our campsite furnished us with a theme for the evening. It was all about Indian history until near midnight. George had read much of Indian history and remembered it all. The professor and I were eager listeners; he outlined the history of the Ojibways now known as the Chippewas. The entire history of the Ojibways or Chippewa Indians was one of loyalty and friendliness to the whites. I had just dropped into a doze when I was awakened by a snuffling and scratching of some animal behind our tent. I caught up my gun and going outside tried to get sight of our visitor, but the thing whatever it was, wolf, Indian, dog or porcupine, scampered away into the darkness without my seeing him. I punched up the fire and laid back down without disturbing my bedfellows. We broke camp early and as but a few logs were met our progress was more rapid. Looking at the map I find our camp for the night to be about four miles below the below the junction of the Thornapple River, a tributary as famous as the Jump River for its giant saw logs, and also famous as a hunting ground for deer and wolves. The wolves are here of course because of the presence of the deer. During the day both George and I took turns hunting the shores. There is a lot of hard wood timber in here, quite as much as there is of pine, which perhaps explains why it is frequented more by deer. They live in the winter, as my father says, on oak and maple boughs. He is perhaps a good authority, as he was born in the forests of Ohio and learned the habits of the deer and other wild animals by hunting with Wyandotte Indians, who were his chosen companions in early boyhood, as the Sioux of Wisconsin had some years ago been mine. The country along the river grows more and more swampy, the river shores are low and water, water is seen everywhere. Hardwood timber instead of pine now crowds the riverbank, the pine being more abundant a half-mile to a mile back. The tracks of deer, wolves and bear are seen and the cries of waterfowl are constantly heard. During the day we made stops to talking things over and to congratulate each other that at last we had got into the real wilds of northern Wisconsin. Several times during the day we heard the particular 'halloo' of the Indian hunter though we did not meet any on the river. It was near sunset when we came to a wilder expanse of the river, in the center of which was a pretty island crowded with a group of great pine trees. It seemed the fittest place in the world for a night's encampment and here we pitched our tent. The surface above the water was about ten feet, and the arms of the great spreading pines completely shadowed every foot of its space. The pine leavers or needles, the remains of years made a carpet several inches thick. The trunks of these noble denizens, isolated from the shore for ages were green with the moss of many, many years. Both the professor and George indulged in man apt quotations pertinent to this encampment. We treated ourselves as first explorers. We saw no tracks of former adventurers. Why should we not exult as Columbus did? The island was a beautiful retreat, fit to be celebrated in classic legend. Last night at its setting we watched the glow of the sun's last rays on the tip top of the great pines on the river's far shore. It was a wonderful picture, and to think that it had been repeated, God only knows how many times in these far away wilds. We sat or lay by our pinecone fire until late. The weird sound in the pine tops made by the wind subsided and all was still save the lone hoot of an owl or the quack of a stray duck. It was solitude pure and simple. Both George and the professor had been in the blankets some time when I laid aside my diary and followed suite. Article

Recently Published Calls Forth Letter from California Man The consistent student of the history of the Chippewa Valley is always well repaid for efforts put forth. From the most surprising places comes stories of incidents that throw light on the facts, and when all it fitted together the truth is readily determined. Not long ago a story was printed that had to do with Jean Burnet, who was one of the valley's first settlers and a gentleman - in every sense of the term. Now note the result, a letter from California, from a former resident here who gives much good material upon which any historian can rely. What he says fits in with what can be found in the interesting little book in the Public Library, by Rev. Barrett, an early Universalist preacher, who wrote about 1864 of "Old Abe," the war eagle. The letter below is from Theodore Coleman, secretary of the Pasadena Hospital Association, and we are thankful for the privilege of printing it. It was sent by the receiver to William W. Bartlett, of the local historical society. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

After

completing our transfer, which took us two hours or so, and again loading

our little craft with camp fixtures, the sudden oncoming of a mass of

logs threatened to wreck us brought us to a halt. We in their mad rush

go thundering and plunging through the boiling cataract. They were ended

over and piled up and hurled about exactly as a lot of corncobs in a

gutter after a June freshet.

After

completing our transfer, which took us two hours or so, and again loading

our little craft with camp fixtures, the sudden oncoming of a mass of

logs threatened to wreck us brought us to a halt. We in their mad rush

go thundering and plunging through the boiling cataract. They were ended

over and piled up and hurled about exactly as a lot of corncobs in a

gutter after a June freshet.  We

had just finished supper when the professor seeing a muskrat in the

nearby slough caught up his gun and slipping down the bank shot the

rat.

We

had just finished supper when the professor seeing a muskrat in the

nearby slough caught up his gun and slipping down the bank shot the

rat. In

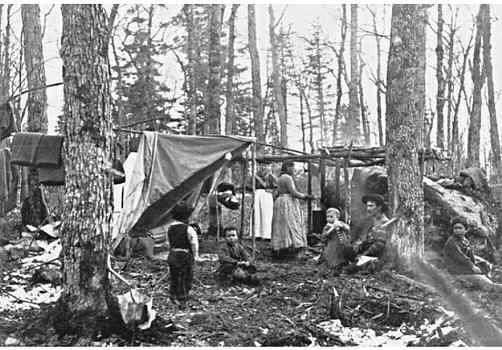

the afternoon we came upon two or three families of Indians in a little

cove just off the river. They were going into camp for the night. We

might have passed them without seeing them but for the barking of their

dogs. The five men of the party were lying about on the pine leaves

smoking long stemmed pipes, while their squaws and children were putting

up poles for their wigwams. We took a vote as to camping near them for

the night, resulting in the negative. We made quite a purchase of maple

sugar, paying about as much as it is worth in Eau Claire. Of course

we were quite willing and even wished to pay all the sugar was worth.

We were surprised though in swapping tobacco and calico for sugar, birch

baskets and the like to find them such shrewd traders. It is well that

they are shrewd for in nearly every other point of contact with the

whites they are easy marks and they can make no defense. For two hundred

years or so since the invading white man began his invasion of this

continent the Indians have been in a state of unrest, have never felt

secure.

In

the afternoon we came upon two or three families of Indians in a little

cove just off the river. They were going into camp for the night. We

might have passed them without seeing them but for the barking of their

dogs. The five men of the party were lying about on the pine leaves

smoking long stemmed pipes, while their squaws and children were putting

up poles for their wigwams. We took a vote as to camping near them for

the night, resulting in the negative. We made quite a purchase of maple

sugar, paying about as much as it is worth in Eau Claire. Of course

we were quite willing and even wished to pay all the sugar was worth.

We were surprised though in swapping tobacco and calico for sugar, birch

baskets and the like to find them such shrewd traders. It is well that

they are shrewd for in nearly every other point of contact with the

whites they are easy marks and they can make no defense. For two hundred

years or so since the invading white man began his invasion of this

continent the Indians have been in a state of unrest, have never felt

secure.