|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

January 25, 2003 - Issue 79 |

||

|

|

||

|

'Indian Hall' restored |

||

|

by SHERRY DEVLIN of the Missoulian

|

||

|

credits: Butch Thunder

Hawk of Bismarck, N.D., on Wednesday talks about Indian objects he and

his college students made to help re-create Thomas Jefferson's "Indian

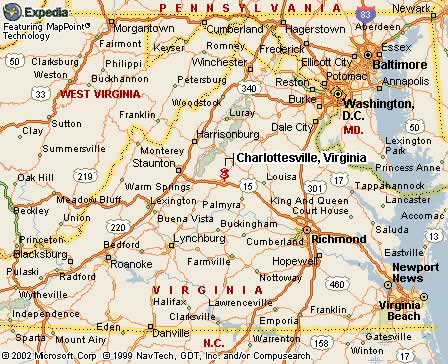

Hall" at Monticello, near Charlottesville, Va. Because Jefferson's

original collection of artifacts - many of which came from the Lewis

and Clark Expedition - cannot be found, new pieces were commissioned

from Indian artists for a bicentennial exhibit at Jefferson's home.

Photo by TOM BAUER/Missoulian |

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. - His prayer transcending 200 years and countless thousand broken hearts, Mandan-Hidatsa elder Gail Baker came to the home of Thomas Jefferson on Wednesday night to bless a collection of artifacts and replicas reminiscent of those given by his ancestors to the explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Baker took care to lift the smoke from his bundle of sweetgrass to each object: shields made of buffalo skin, arrows with tips carved from buffalo bone, deerskin leggings with porcupine quillwork, a hand-painted buffalo skin map of the Missouri River as it was known before Lewis and Clark extended the reach of that knowledge. His nephew filled the silence in Monticello's ornate entranceway with a song of blessing, playing a flute he carved from cedar in the fashion of the Mandan-Hidatsa people. His wife tended the sweetgrass, adding her low amen to the prayer. Finally, Baker spoke to the three dozen onlookers curators and docents from Monticello, the Indian artisans who created the replicas, and journalists from across the United States. "I am quite honored to be here," he said, his voice breaking with emotion. "This is the first time I have come up here." It is, in fact, a week of such firsts at Jefferson's mountaintop home, which is hosting the inaugural event commemorating the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. But then, it has always been that way at Monticello. It was from the home he built overlooking Charlottesville that Jefferson wrote Congress 200 years ago this week asking for $2,500 to send an expedition into the unmapped portions of the North American continent. Here, he selected two of his Albemarle County neighbors to lead the exploratory corps. Here, he wrote their transcontinental to-do list, emphasizing the importance of recording all that they saw. Too anxious to wait for the expedition's conclusion to see something of their collections, Jefferson instructed the explorers to send back all that they could before leaving their winter quarters and venturing forth into territory previously uncharted by white men. Among the objects Lewis and Clark sent to their sponsor were gifts from the Mandan-Hidatsa people who provided the expedition with food and shelter during the winter of 1804-05. Animal skins. Bones. Elk antlers. Buffalo robes. Indian pipes, leggings and pottery. The tribe's map of the Missouri River and its tributaries between the Platte and Yellowstone rivers. Many of those objects eventually arrived at the president's home and were arranged in the house's two-story entranceway, creating what Jefferson called his "Indian Hall." Remarked upon by scores of Jefferson's house guests in the years that followed, the artifacts mysteriously disappeared when he died in 1826. The collection's fate remains unknown, despite considerable efforts to locate it for the bicentennial commemoration, said curator Elizabeth Chew. "Honestly, I kept thinking I would find a buffalo robe at a fraternity house at the University of Virginia," she said during Wednesday night's preview of the re-creation of Indian Hall, a bicentennial installation called "Framing the West at Monticello" and due to open to the public Thursday. With the exception of the elk antlers sent back East from the Mandan villages, none of the artifacts were located. So Chew commissioned Indian artisans to reproduce the objects. In Bismarck, N.D., Butch Thunder Hawk put his technical college students to work on shields, bows and arrows, pipes and clubs. On the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, JoEsther Parshall spent a year producing a pair of leggings and mocassins adorned with intricate quillwork. Dennis Fox traveled to the Peabody Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology at Harvard University to study buffalo skins painted by Mandan-Hidatsa warriors. "Most of my life, I've been doing this work, learning from my grandparents," Thunder Hawk said. "For this work, I did a lot of thinking. I talked to my family to get their blessing, and make sure it was OK for me to take this project on. "It opened my mind to the Lewis and Clark Expedition and to the other tribes," said Thunder Hawk, a member of the Hunkpapa Lakota Tribe. "Hopefully, during this bicentennial, we will all make better connections." The bicentennial years 2003 through 2006 are an opportunity for Indians and non-Indians to put away the sadness and anger of the past, and to replace it with understanding and respect, said Keith Bear, the nephew of Gail and Rosemary Baker and a Grammy-nominated flutist. "We are all native Americans," Bear said. "We were all born here, just like the grass. My people have never looked at the outside of others and seen the differences. We understand that we all come from this earth, that we all have one heart." His words echoed those delivered earlier in the day at the opening session of the coinciding conference on "Jefferson's West" at the University of Virginia, the institution founded by Jefferson in his hometown shortly before his death. The 200th anniversary of Lewis and Clark's journey is an opportunity for Americans to awaken from their self-imposed sleep, said historian James Ronda, author of "Lewis and Clark Among the Indians" and "Jefferson's West: A Journey With Lewis and Clark." "The West that Jefferson imagined from Monticello was a fantasy," Ronda said. "In Jefferson's mind, the West was a place where nature ran loose and unchecked, where there could be no real homes or families. It was a place that needed to be tamed." Lewis and Clark headed West believing it to be "the big empty" a myth then, as now. Travel brochures and advertising campaigns perpetuate the myth as much in 2003 as did President Jefferson in 1803, Ronda said. But the territory beyond the Mississippi River was never "wide open spaces where everywhere is miles from nowhere," he told the conference's 1,000 attendees. "And it certainly isn't now." For thousands of years before the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the West was home to the Mandans, the Blackfeet, the Nez Perce and Chinook, the Salish and Kootenai, and dozens more Indian tribes. There were families and villages and trade centers. There were stories and histories, and a geography of great complexity. "Jefferson's West was this theme park of the mind," Ronda said. "It was a place made of clay, that you could mold and shape as you chose. In the West, you could create your own Eden. "And Americans did just that in the century following the Lewis and Clark Expedition, in the process driving out those who called it home." The Mandan-Hidatsa people couldn't possibly understand the idea of the Louisiana Purchase, he said. How could the American president pay $15 million to the French emperor Napoleon for the vast Western wilderness? "It made no sense," Ronda said. "The French had nothing to sell. They could not sell what they did not own. These ancient cultures did not buy and sell land. They did not own land; it was not theirs to own." The bicentennial is an opportunity to recognize and discard the enduring Western myths, he said. "This commemoration from this moment to 2006 is an opportunity to enrich our sense of the past," Ronda said. "There is not one story, but many stories, and they need to be told in many ways."

Reporter Sherry Devlin can be reached at 523-5268 or at sdevlin@missoulian.com.

|

||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||