|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

November 16, 2002 - Issue 74 |

||

|

|

||

|

Washington Tribes Invest Casino Proceeds by Sending Members to College |

||

|

by Lynda V. Mapes Seattle

Times staff reporter

|

||

|

credits: Photos

by Alan Berner Seattle Times

|

|

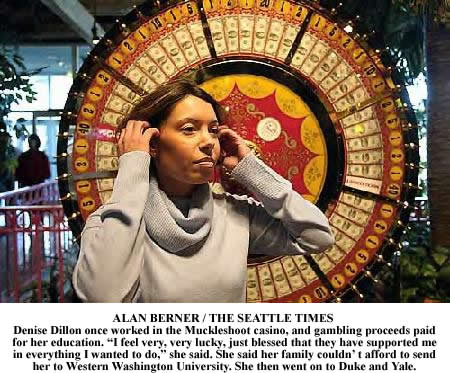

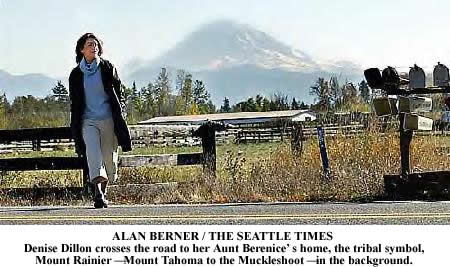

But neither imagined Denise would go so far. Denise Dillon is the first in her family to go to college and the first in her tribe to earn advanced degrees from major East Coast universities. Her remarkable journey is made more so by the fact that it was gambling that made it possible. The Muckleshoots are one of only a few Washington tribes that own a profitable casino, enough so that the tribe is spending almost $1 million this year alone on scholarships for 132 tribal members. For Dillon and others, the casino profits and the tribe's commitment to education allowed them to beat the odds. In Washington, only about 4 percent of Native Americans earn graduate or professional degrees, compared with almost 10 percent of whites. Dillon received a full-ride scholarship to Western Washington University in Bellingham, and two years for her master's degree in health sciences at Duke University in North Carolina. In August, she graduated from the physician assistant surgical residency program run through the Yale School of Medicine. After years of schooling, Dillon is looking for her first job as a surgical assistant. "I feel very, very lucky, just blessed that they have supported me in everything I wanted to do," said Dillon, who was given the money for her education as a gift — no strings attached. It made all the financial difference for her family, Dillon said. "We couldn't even swing Western." A mother's determination Petite and poised, Dillon's warm smile and easy manner mask a steely determination. She happily pilots her father's big black diesel pickup as she rumbles around the reservation. She already has lit a path in her family. Her 22-year-old cousin George Lewis is enrolled at the University of Washington. Their success underscores how much has changed in just two generations. The tribal casino, which opened in 1995, was built where Dillon's mother, as a child, collected drinking water in empty milk jugs. Once a week, the water went on the woodstove for bathing by the light of a kerosene lamp. "When we grew up there was no running water, no lights," Schultz said. "We didn't think of ourselves as poor. We had the woods, the family, the church — it was fun. We didn't know we were poor, until we left the reservation." Schultz, 54, never made it to high school. She cleaned houses, managed restaurants and later dealt blackjack at the tribal casino. Her daughter is the first woman in her family to postpone marriage and having a family to pursue a professional career. Her mother is a big part of the reason: Schultz is an avid reader who shared her passion with Dillon. And she was determined that her daughter go further in school than she did. It was not to be an easy journey. Hit head-on in a car crash by a drunken driver when she was 17, Dillon spent most of her senior year in high school in a wheelchair. She was told she would never walk again. "But she was so determined, she was pulling herself up the walls, trying to walk," Schultz said. After bone grafts, surgery and an assortment of rods and pins in both legs, Dillon accepted her diploma from Yelm High on her feet. Dillon still can't run, and even standing for long periods of time can be painful. She's been warned that she may not be able to walk past age 40. But in her trademark style, Dillon says she learned something from her ordeal. "I learned a lot about what a good health-care provider is," Dillon said of her year of rehabilitation. "They put the patient first." Dillon, now 28, said she was attracted to studying surgery because of the technical challenges and the interaction with patients. "Usually in surgery you have patients who are more scared than they will ever be in their whole life. You can let them know you care about them and they are going to be OK." 'They are too proud of me' Just leaving home — an unremarkable step for a non-Indian teen — is a profound cultural break for many Native Americans. She still tears up at the memory of being across the country and unable to leave classes at Duke when relatives died, including her Uncle Pun — Clarence Courville, who was deeply involved in making the arrangements with the tribe to pay for Dillon's schooling. "I never could have done it without him. "But you can't do two things at once. ... You can't come back for every illness, every funeral, you would be here all the time." And school, particularly back East, was difficult. Raised in a tribal tradition of modesty and cooperation, Dillon was confronted by Yale's competitive atmosphere. "You have to be much more aggressive, and that is not something we are taught. We are taught to cooperate and work as a team," Dillon said. "Surgery was very different, very competitive, very cutthroat. That's not the type of person I am, but I had to hold my own." Dillon said she stayed quiet, instead of talking herself up. "One of my friends said, 'You are so smart, but you just sit there like you don't know anything. You never say the answer even though you always know it.' " Still modest about her success, she said: "It's about working hard and setting goals and doing what you have to do to achieve them. Anyone could do it if they tried hard." But everywhere she goes on this reservation, with 1,600 tribal members, she's greeted with hugs and congratulations. "It's almost like they are too proud of me," Dillon said. "I didn't save the world. I'm not the president." Tribes emphasizing education For those tribes that can afford it — and that usually means the few with profitable casinos — education has become a priority. The Tulalip Tribes have spent about $5 million on scholarships since its casino opened in 1992. The tribes graduated their first Ph.D. from Stanford this year. The Tulalips, with 3,500 enrolled members, will spend about $1.2 million this year alone on scholarships to anyplace tribal members' ambitions take them — graduate school, two-year and four-year colleges or vocational school, said John McCoy, director of governmental affairs. The Puyallup Tribe will send any tribal member to the school of his or her choice, full ride, at any age, as long as the student maintains at least a 2.7 grade point average. "It's something you could only dream of before," said Frank Wright, general manager of the tribe's casino. His son Chad has gone through Boston College, the law school at Pepperdine University, and is now enrolled in the business school at Stanford, all on tribal scholarships. "The better care we take of our kids, the more able they will be to go anywhere in the world," Holmes said. Education is a first priority for the Muckleshoot people, said John Daniels Jr., chairman of the Muckleshoot tribe. "When we had bingo, we could help out a little," Daniels said. "But now it's anywhere you can get in, it's covered. And if we had a cutback, that would be the last one." The tribe puts a percentage of casino revenues into an endowment every month to ensure money will be there for the education of future generations. The tribe also encourages kids to stay in school, rewarding them with free trips — even to Hawaii — for themselves and a chaperone if they graduate from high school. Casino money also enables the tribe to buy school supplies and new school clothes for tribal children "so they can go to school with their head up," Daniels said. A child-development center set to open later this year will have classrooms for nearly 1,000 children a day, including, eventually, non-Indian children. It's a big step up, Daniels said, from when there was only one car per neighborhood on the reservation and tribal members took turns pushing it through rutted mud driveways to get to the grocery store. He remembers having outhouses, and how the septic tanks were dropped off in tribal members' yards by the federal government but never installed. "We used to play on them," Daniels said. He looks at Dillon with pride and affection, saying simply, "She has done great." A tan baseball cap Dillon brought

him, emblazoned YALE, sits on the shelf above his desk. It's displayed

along with his other prized possessions, a totem of mainstream success

not only for Dillon, but for the entire tribe.

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

MUCKLESHOOT

INDIAN RESERVATION, WA - Having never made it past the eighth grade,

Cathleen Schultz wanted more for her daughter. It wasn't a question

of if Denise would go to college, but when, her mother would say over

and over.

MUCKLESHOOT

INDIAN RESERVATION, WA - Having never made it past the eighth grade,

Cathleen Schultz wanted more for her daughter. It wasn't a question

of if Denise would go to college, but when, her mother would say over

and over.  "People are beyond survival now, they are making plans for the

future," Dillon said. "I hope someday they'll be saying, 'Oh,

Denise, she only went to Duke and Yale and was a physician's assistant.

Now we have 10 doctors from the tribe.' "

"People are beyond survival now, they are making plans for the

future," Dillon said. "I hope someday they'll be saying, 'Oh,

Denise, she only went to Duke and Yale and was a physician's assistant.

Now we have 10 doctors from the tribe.' "  "The

community is so close, they don't leave," Dillon said. "They

stay here. It's very, very rare that they leave, and if they do it is

usually to make connections with another tribe. The whole community

stays home. And there is never really a good time to leave."

"The

community is so close, they don't leave," Dillon said. "They

stay here. It's very, very rare that they leave, and if they do it is

usually to make connections with another tribe. The whole community

stays home. And there is never really a good time to leave."  Even

the tiny Kalispel tribe in Usk, Pend Oreille County, with just 339 members,

is sending 20 percent of its adult population to college, all with proceeds

from the casino opened on tribal trust land outside Spokane in December

2000, said tribal council member Curt Holmes.

Even

the tiny Kalispel tribe in Usk, Pend Oreille County, with just 339 members,

is sending 20 percent of its adult population to college, all with proceeds

from the casino opened on tribal trust land outside Spokane in December

2000, said tribal council member Curt Holmes.