|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

November 16, 2002 - Issue 74 |

||

|

|

||

|

Bridge to the Past |

||

|

by Sherry Devlin

of the Missoulian

|

||

|

credits:{credits}

|

| Mythic 10,000-year-old tradition

of netting salmon is being kept alive by the Indians along the Klickitat

River in Washington

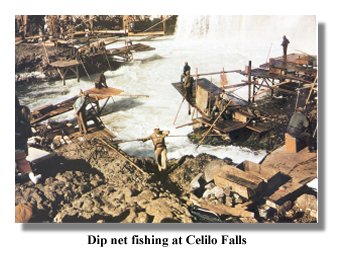

They learned the old ways from their fathers, who learned from their fathers. To come here, the men explain, is to honor those who came before. To bring their sons here, they say, is to honor those yet to come. Fearlessly, they climb down the canyon walls and onto platforms suspended above the river. Gracefully, they dip their nets into the darkest pools. The platforms shudder and bend. The men work the current, hurriedly twisting and lifting the 30-foot-long poles when they feel a fish. The salmon do not give in easily. They, too, are here to honor the old ways. They left these waters as infants; they return as adults, fattened in the ocean, forced around dams and a flotilla of fishing boats, finding at last the stream where they were born. The most skilled of the men pull two, sometimes three, fish from the water at a time, hoisting their catch onto the skinny platform and clubbing it to death. They work without speaking, content in the great and ancient beauty of their dance. Only the duct tape they use for repairs gives them away. This day, they have come to catch coho for the longhouse in Celilo Village, the oldest of the tribal gathering places on the Columbia River. Tomorrow, they will give thanks for the harvest, roasting the salmon over alder-wood coals, complementing it with venison and berries, blessing it with a singsong prayer.

Wilson Begay grew up with stories of how things were before the Columbia - Nch'i-Wana - was dammed and its waters stilled. By the time he was born, Celilo Falls had been silent for 10 years. Begay's grandfather - the chief of Celilo Village - caught his first fish at the falls when he was 12. His grandfather showed him where to dip the net; a steelhead soon fulfilled the boy's wish. He packed it home whole in a burlap bag. "The elder ones knew the river," Begay says. "They remember." His mother and aunts sold salmon to the tourists. "This place was like Niagara Falls," one aunt says. Every morning, the girls sold fish to passers-by. If they did well, their father paid them each a dollar - "big money" - enough to go to the movies. Celilo Falls was a series of islands, rapids and narrows that dropped the middle Columbia by 22 feet. It was the most productive Indian fishery in the Americas and the centerpiece of the continent's longest-lived human settlement. For 10,000 years, native people collected the Columbia's mythic runs of salmon as they pooled at the base of the falls, then leapt into the fracas. There seemed no limit to the bounty. Tens of thousands of fish were netted, speared and gaffe-hooked. Tens of thousands more were allowed to pass the fishermen by, so they might reach the distant streams and reproduce. The water howled, the village reeked of fish, the people came and were sustained. All of the tribes used this place: the Nez Perce, Yakama, Umatilla, Warm Springs and more. Dozens of others traded with the river tribes, some from as far away as Central America, asking always for the big ocean-fed salmon. Celilo Falls was "the great emporium of the Columbia," said Pacific Fur Co. trader Alexander Ross. "It was mecca," said historian Bill Lange. When, on March 10, 1957, the gates closed on The Dalles Dam, it took but six hours for Celilo Falls and then the Indian village to disappear in the rising waters, taking with them the salmon and their people. "It was a sin for white men to destroy God's creation," Begay's aunt whispers. "They never understood. It wasn't just Celilo. It was the whole river." "There are a lot of stories and beliefs about these fish," Begay says. "The salmon gave himself so we could live." All that remains of Celilo Village is a strip of trailer houses and a cedar longhouse, crushed between the walls of the Columbia Gorge and Interstate 84, 20 miles upstream from The Dalles. Fifty people live here now, Begay and his grandparents and cousins. They have no store or paved streets, and nowhere to grow. They stay, Begay says, for the same reason that they fish: to protect their rights to this place, because it is something worth saving. Because Celilo had lost its falls, Begay learned to fish on the Klickitat River, in the narrow canyon two miles from its junction with the Columbia. Now he has sons of his own, 8-year-old Cody and 11-year-old Jason. Someday soon, they will be strong enough to manage the big fish and bigger dip nets. The youngest boy plays hide-and-seek in the boulder field that sits atop the canyon - volcanic rocks, split apart by a thousand flood tides. The older boy helps his father load the afternoon's first dozen salmon, slimy 15- and 20-pounders. Their cousin works the water from a tiny platform on the opposite side of the canyon. The fishing is not without danger. The Klickitat falls once, twice, three times as it threads the narrow canyon. The only footholds in the canyon walls are those created by erosion. The fishing platforms are scarier yet. Not to worry, Begay says. The fishermen tie a rope around their waist, to catch them if they stumble. And if it does not? He looks up from his fish-tending. "They perish."

When there was nothing left to do but watch the water rise, Jay Minthorn told his friends he would like to stay and catch the last fish at Celilo Falls. One of the women took his photograph and later put it on the wall of her house with the caption: "Jay trying to catch the last fish." The saddest part was when the fishing platforms began rocking, then disappeared beneath the water. "It was like a funeral, these things being destroyed and lost," Minthorn says. "Nobody took out their scaffolds. They belonged to Celilo. A lot of us left our nets there, too. We let them go." Anymore, it's hard to convince young people that the river once ran free and full of fish. Minthorn has a home movie of the falls that he shows his grandchildren. "They don't believe it," he says. "My granddaughters just went down there," he says. "I spoke to the grade school and showed the video and explained about the unique Celilo Falls. But they were kind of doubting my words because they've seen what's left of Celilo Village. They've seen what it has become." Everything was different before the dams were built, Minthorn says. You could dip a cup of water from the river without fear of sickness. During the height of the runs, men stayed out on the islands, sleeping in caves, dipping and spearing salmon day and night. The river was half the width of the post-dam reservoir. Its water ran with a fury. The village went for miles and miles on both sides of the river. On the islands and riverbanks, the rock art told stories of a thousand generations of fish and fishermen. "After I got older, I wondered how many of our ancestors done the same thing we did," Minthorn says. Minthorn's family would drive from the Umatilla Indian Reservation to Celilo Falls in long, slow caravans. There were fishing places all along the way, he remembers, and people they knew and looked forward to visiting. "It was a three-day trip, but the tribes were patient people," he says. The tribes were poor, but the salmon sustained them, Minthorn says. "The worst part was losing our traditional fishing ways. When they flooded Celilo, they gave our elders a salesman talk. 'Don't worry about it,' they said. 'We'll double the runs.' The tribes have been fighting to make them double the runs for nearly 50 years now." Minthorn is on the Umatilla tribal council now, and represents his people on the Columbia River Inter-tribal Fish Commission. Nowadays, he says, most of the talking is done by lawyers. Increasingly, the tribes have relied upon the legal system to enforce their treaty rights. "We have lost so much," he says. The treaties guaranteed the tribes access to their usual and accustomed fishing places, and to healthy runs of salmon. Development and illegal land sales took away their access to rivers; commercial fisheries, logging, irrigation and dam-building took away the salmon. A recent Inter-tribal Fish Commission report tells the story: "Initially, the losses of salmon were caused by competing non-Indian harvesters, and obstruction or denial of access to usual and accustomed fishing places, sometimes fenced off by non-Indian property owners. Most of these actions were eventually challenged in court, and struck down as illegal. With each court affirmation, the tribes looked forward to once again sustaining their people with the salmon. "But over time, when tribal people were once more able to return to the river, they found the salmon were no longer there. For during the struggle to reaffirm the right to treaty access to fishing, another tribally adverse process had been occurring - the transformation of the rivers to produce electricity, irrigation for agriculture, navigation services and waste disposal. Increasingly, this transformation left no place for the salmon, and hence, little place for the tribes. "As each dam was constructed, the tribes objected, calling on the government to reconsider, pointing out that these actions were contrary to the treaties the United States had signed with them, and predicting adverse consequences for the salmon - and for their tribal peoples. Each time, these tribal objections were ignored, given little weight, or actively opposed by non-Indian interests - and tribal salmon harvests continued to decline." Now, 90 percent of the wild salmon have been lost. After the Corps of Engineers built their last series of Columbia Basin dams on the lower Snake River in the 1960s and '70s, all runs of coho dependent upon that corridor disappeared. All of the inland West's salmon are predicted to be extinct by 2017. There have been successes in recent years, Minthorn says. The Yakama Nation has restored coho and fall chinook on the Klickitat River - where the men of Celilo Village now fish. But those salmon have but one dam to negotiate on their upstream spawning migration: Bonneville. Other fish have eight dams - and that, Minthorn says, is too much to ask, even of a salmon.

When the people arrive, the fish are hanging from the eaves of the longhouse, sliced lengthwise so the blood will color the meat red. They are gifts, the fishermen say, for the elders to carry home. Inside the longhouse, the people trade their town clothes for tribal shawls and vests. The women pull loose dresses over T-shirts and jeans, and take seats along the left side. The men remove their jackets and take fancy vests out of plastic sacks, then find seats along the other wall, facing the women. This is the day of Celilo Village's harvest festival, and also the day to remember those who have passed this year. An important man has died, a grandfather to many. His family is here to release themselves from mourning. They have not hunted or fished since he died. They have not danced. By the time Chief Howard Jim rings the bell and begins his prayer, the longhouse is lined with more than 100 people - most from the Yakama tribe, although all are welcome. Jim uses the occasion to school the young people - the teen-agers in baggy pants and bandannas - in the old ways. "This is the way we keep our traditions," he says. "We pass this knowledge on to you." As Jim speaks, the dead man's family carries in belongings for his "give-away" - a dining room table, an electric fan, dozens of blankets and towels, flannel shirts and wool sweaters, a garbage sack filled with children's toys. Outside, the fishermen arrive with alder wood and a pair of king-sized coolers filled with last night's catch of Klickitat River coho. Inside, the women have butchered a deer and filled bowls with the steaks. When the coals are white-hot, the meat will be prepared. Charlton John went away for high school - "to the reservation" - but missed the river and the fishing too much to stay past graduation. The Yakama Nation's reservation is miles from Celilo, he says. It is too far from here, and too dry. "I've got my gramps here," John says. "We do a bit of work, and I keep him company. I tried to live on the reservation, but that's not for me. I just want to stay home and fish. I am freer here." His relatives call him "Ace," in honor of his skill as a fisherman. John introduces himself by his given name, and does not boast. Even one fish a week, or two, will keep him alive, John says. He's put away a good supply for the winter, enough for his gramps and his sister, too. He'll take some fish to his aunts and uncles. His aunts will dry some of the meat and can some. When the commercial season opens, John will work the Big River. Until then, he'll fish the smaller streams. When the catch is good, John sells salmon out of the cooler he keeps iced outside his trailer. This day, a pair of tourist women see his spray-painted sign from the interstate and pull into the village. He sells them a 7-pounder for $4 a pound. The best customer of the day, though, is a fishing guide from Lewiston, Idaho, named Chuck Taylor. He wants 50 pounds of coho eggs, and is willing to pay $4 a pound. "You keep the fish," he says. "I just want the eggs." John and his cousins expertly lift last night's catch of silver salmon from their coolers, slice open the fat fish bellies and remove the egg strands. A dozen, then another dozen fish are opened as John fills a pair of plastic bags with the brilliant red eggs. "We'll use these as bait for the steelhead run," says Taylor, who guides fisher-people on the Snake and Clearwater rivers. "We prefer steelhead eggs, but these are just about as good." Gingerly, he situates the eggs in ice chests on the back seat of his sedan. They'll be cured at the outfitter's shop in Lewiston, then sold by the ounce to clients. "I'll be back in a few weeks," he promises. "These are beauties." Night is falling on the narrow canyon of the Klickitat when 11-year-old Jason Begay comes running across the boulder field. "They're waiting at the bottom," he shouts. "Hundreds of them." His older cousin - the fisherman called Ace - nods. "The fish will start moving up the falls soon," he explains. "They wait for it to get dark. They think we won't be able to see them." All the others have left the fishing platforms, chased away by hunger and the damp nighttime cold. John makes the tightrope walk across the two-log plank to the other side of the canyon, teetering just a bit in mid-crossing. He picks his way across the canyon walls, mountain-goat style, and lowers himself onto the smallest, lowest platform. Quickly goes the rope around his waist, tethering him to the cliffs. Deftly goes his dip net into the water. The salmon have come, as young Begay predicted, and the water boils with their antics. They flip and twist. They push and shove. John joins the dance, dipping the net as deeply as he can without falling into the water. His stepfather's father fell into these falls and was never found, John says. His bones are in the water still - with the others, the ones who came before. One, two, eventually six fish fill John's net as he lifts it from the river. He stops only to pull a stocking cap over his head, and to load salmon into gunnysacks. Always, he works in silence. Begay lowers himself into a little seat carved into the cliff by a thousand-thousand rainstorms. He watches the fish and his fisherman-cousin, and dozes. Soon, he says, it will be his time. Maybe next year. They will celebrate his First Catch in the longhouse. The hour grows late, the fish move upriver in great number, and the man and boy keep the tradition of their grandfathers, pulling salmon from the water in a hidden canyon, two miles and 10,000 years from town.

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

LYLE

FALLS, WA - In a hidden canyon of the Klickitat River, a half-dozen

Indian men observe a 10,000-year-old tradition, dipping long-handled

nets into the water, in search of salmon.

LYLE

FALLS, WA - In a hidden canyon of the Klickitat River, a half-dozen

Indian men observe a 10,000-year-old tradition, dipping long-handled

nets into the water, in search of salmon.