|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

September 7, 2002 - Issue 69 |

||

|

|

||

|

College Seeks to Begin New Tradition of Crow Farming |

||

|

by Carrie Moran McCleary for

The Billings Gazette

|

||

|

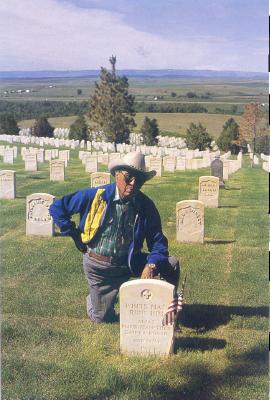

credits: Photo of

Joe Medicine Crow

|

BLACK

CANYON - Like those who came before them, in a culture of traditions,

folks at Little Big Horn College are turning to their elders for answers. BLACK

CANYON - Like those who came before them, in a culture of traditions,

folks at Little Big Horn College are turning to their elders for answers.

And Joe Medicine Crow, a tribal historian, had some answers for LBHC officials, Montana State University and ranchers who want to know why so few Crow Indians look to agriculture as careers. A chat with many older people on the reservation will bring memories of the farms on which they grew up - primarily small subsistence farms that had a few cows, a large garden, hay and, of course, horses. Medicine Crow, 89, remembers those farms and when so many of his fellow tribesmen left them. His vivid and saddest memory is the one he says broke the heart of the Crow people. "In 1919 the farmers complained that the Indian ponies were eating up all their grass they were paying 30 cents an acre to lease," Medicine Crow said. About 1920, the Bureau of Indian Affairs superintendent ordered the roundup of all Indian ponies on the Northern Cheyenne, Crow and Wind River reservations. Many of the horses roamed across the reservation, often unbranded. A rancher contracted to exterminate all wild horses. Tribal members had two months to find their horses and bring them in. "These horses were tough," Medicine Crow said. "We had to fight all these stallions. Finally, about one week later we brought home only about 30 or 40 head. A lot of people got them in and branded, but most didn't." The rancher's cowboys killed the wild horses and received government pay of $4 per pair for ears cut from the ponies. "Some Indians did it for a while, too," Medicine Crow said. "But the government only gave them $2 each pair, and then the elders told them, 'Stop that. These are your brothers,' so they did." The cowboys also tired of the horse deaths, so the rancher brought in gunmen from Texas. "It was terrible," Medicine Crow lamented. "You go out there, and there were dead horse everywhere. And soon all those horses were gone, and they started to come in and get the horses at our places." Finally, the government called a halt. Officials said 44,000 horses were killed, "but it was way more than that," Medicine Crow said. He said this tragedy, followed by insensitive opportunists who hauled wagonloads of horse bones to Billings fertilizer plants, was just one reason the Crow turned away from farming. He said many farms were deserted during the Dust Bowl when the wage labor of the Indian Emergency Conservation Works program, the reservation version of the Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Projects Association, came to Indian country. Medicine Crow said Crows left their farms "Grapes of Wrath"-style and moved into tarpaper-shack "dog towns" near the IECW camps. Little Big Horn College Professor Tim McCleary said the 1930s and early '40s were actually somewhat of a boon for the Crow. "The reservation had never experienced large-scale wage labor before," he said. "People left their farms and moved to town. But many returned to their allotments while on leave from work .... For their white neighbors experiencing the Depression these were hard times, but the Crows had never had money before." Medicine Crow said some Crows did return to their farms after "the dust," but found their equipment vandalized, stolen or in ill repair. Tenacious farmers who returned to the land found additional heartbreak. "For the next couple years we had a little water again but the Mormon crickets came," he said. "You could hear them coming, and, when they left, there was nothing left." Crows began leasing their lands to neighboring non-Indian farmers who could get loans at the bank and often had the expensive equipment needed to farm larger tracts of land. "For all practical purposes, that dry spell killed Crow Indian farming," he said. Now, Gail Whiteman, LBHC agri-business curriculum development project coordinator, said most Crows look to agriculture to ranch, rather than farm. LBHC launched the agriculture program last spring. Whiteman said she would love to have 20 students this fall but so far has 10. Registration continues through Tuesday. "I will be happy with 10. It takes time to get this going," she said. She said today's obstacles for Crow producers include lack of a land base, financing and a history of farming in their families. U.S. Department of Agriculture subsidies "don't reach far enough to educate people," she said. "Not having any agriculture in the families for the last 80 years, with that history of how to fill out the mountain of paperwork, the bookkeeping and the business sense is a real obstacle," she said. Farm Service Agency Public Affairs spokeswoman Heidi Brewer said Big Horn County farmers accessed just $15 million in federal farm funds in the 2002 fiscal year. Of that, about $356,000 was earmarked specifically for American Indian programs. But she said all of these programs are open to all races. Brewer said producers in Big Horn County can seek help at their local Farm Service office in Crow Agency or Hardin. And LBHC has two other programs in-house that can help producers looking to get started. The Crow Land Owners Association helps Crow land owners understand their rights as land owners and programs available to help them use their land. And the Farm Service Agency liaison helps producers understand the paperwork needed to access its programs. Whiteman wants Crow ranchers to take more control of their ground, so each would have a sustainable smaller operation they could handle themselves. "Then have those producers form a co-op, and they would have maybe 15,000 calves, so when buyers come they are competing for 15,000 calves, not 150 head at a time," she said. Whiteman also want to get high-schoolers into 4-H and Future Farmers of America; "get them into youth loans so they can raise some livestock; and get them acclimated to the ag way of life." She envisions an Apsaalooke 4-H chapter that fits Crow culture and competes nationally with other reservations and tribal colleges. Her short-term goals include continuing to write grants in cooperation with agriculture college staff at Montana State University. She is working on an articulation agreement between LBHC and that institution and seeking its advice for scholarship and grant possibilities. She would like to have an experimental station and an arena for equine classes. "We live in the golden triangle of agriculture in Montana. We are a land-grant college," Whiteman said. "And we need to be an agriculture college."

|

||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||