|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

August 24, 2002 - Issue 68 |

||

|

|

||

|

Tribes Fight to Keep Native Culture Alive |

||

|

by Paul Sukovsky Seattle

Post Intelligencer Reporter

|

||

|

credits: photos

- Mike Urban, Seattle Post-Intelligencer

|

| Indian tribes that once made their

homes on protected Puget Sound coves or along rivers tumbling out of the

Cascades have disappeared.

Some others are barely hanging on. The Gig Harbor Tribe is gone. So, too, are the Montesano and the Satsop people. And the descendants of the Noo-wha-ha have been absorbed by modern-day tribes. These tribes succumbed to politics and war and European diseases for which they had no immunity. They were left without land when the United States imposed treaties in the 1850s that provided reservations for some, but not for others. Some of these landless tribes, such as the Chinook and Duwamish, still have not been recognized by the U.S. government and are precariously clinging to their native roots. Here, in the Pacific Northwest, icons of native culture define who we are -- salmon, clam digging and the names of the places in which we live -- Seattle, Snoqualmie and Snohomish. Over the years, some tribes have melted into the general population or melded with other Indian nations. This is the story of three tribes tenuously hanging on to their heritage.

But every year, about the end of July, you'll find him doing the same thing his native ancestors from the Mitchell Bay, or San Juan tribe, have always done. Just off a point of land jutting from Stuart Island -- a place where Indians have used reef nets for thousands of years -- Chevalier owns a reef net location at the mouth of Reid Harbor. It's the perfect spot to intercept the rich sockeye salmon schools as they migrate past the shore. The native people of Puget Sound and the northern straits invented reef netting in ancient times. This site has been passed down through generations of the Chevalier family to Charles, who is one of only 11 people who still hold state reef net licenses in Washington. But Chevalier, who is of one-quarter native blood, is part of another tiny group. The San Juan or Mitchell Bay people no longer sing the sacred songs or dance the sacred dances. There is no tribal organization or even a membership roll. And the tribe is not recognized by the federal government. Still, the echoes of Indian life resonate in a generation younger than Chevalier, 72. Pioneer families throughout the San Juans are infused with Indian blood. Nieces, nephews and cousins of the Chevaliers are scattered around the archipelago. Among them, people such as Nick Nash, born 50 years ago on San Juan Island. Nash, of Friday Harbor, says he doesn't "have the cultural background to feel like an Indian raised on the reservation." But like his cousin, Charles Chevalier, he lives like one. Chevalier doesn't say much about the songs and traditions by which Indians used to call fish to their net. But when asked about the totemic drawing of a killer whale on one of his reef net rafts, he laughs. "I guess I can't help it being part Indian." Indians around Puget Sound know where they come from; they know who they're related to and the places where their people live -- have always lived. Chevalier is no exception.

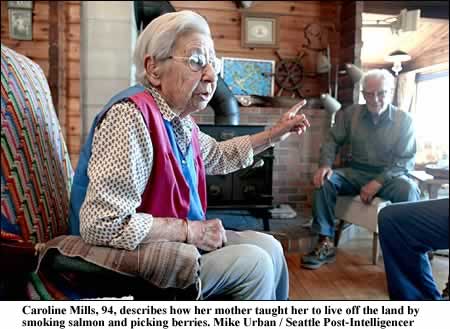

Mills, known by everyone as Toots, credits her mother with teaching her how to live off the land by catching and smoking fish and picking berries. A huge grin transforms the old lady's lined face as she recalls growing up on these remote islands. "Along this beach here there was nothing but Indian camps," she says. "Saanich, from Canada, used to come up in big long canoes; you could hear them singing on the water. "And when the owl used to land on the fence, my great-grandmother would go out and talk to the owl and it would land on her hand." Among many native people of the Northwest coast, the owl is a harbinger of death. Nash, who has always made his living as a fisherman, sees that way of life dying -- just as his tribe has. With native blood on both sides of his family, Nash, who is three-sixteenths Indian and an associate member of the Swinomish Tribe, is harnessing that fierce sense of belonging to protect this place he loves so much.

"I'm tired of seeing plastic bags and Styrofoam around this place. It used to be a pristine environment." So Nash has begun working with the Friends of the San Juans, which bills itself as the voice for the environment of the San Juan Islands and the northern straits, to restore the habitat with an eye toward revitalizing the fishery. "I've lived here my whole life," he says. "I love being on the water. "And I am going to be exterminated. I'm one of the last fishermen on this island." Just across the street from Nash's house you'll find his aunt, Marge Workman. Workman, 80, reminisces about some of her best friends, Indians raised on the islands who are gone now. "There isn't any of them left here on the island except our family," she says. "We didn't get any allotment land in San Juan County. "It's sad. There isn't any recognition of our ever being a tribe. That's what I am. I am a San Juan Indian. "The Indian ways are going to disappear from these islands."

He's not. But he easily could be dubbed "relentless" for his efforts to help his Snohomish people survive as a tribe. This 78-year-old elder and tribal historian is the great-great-great-grandson of Snah-talc, or Bonaparte, the subchief of the Snohomish. It was Bonaparte who placed his "X" mark upon the Treaty of Point Elliott in 1855. The treaty promised a reservation at Tulalip near Marysville where the Snohomish and other tribes could live. According to Kidder, some of the Snohomish moved there. "But in short order, they had to leave," says Kidder. "There was no way to make a living, at least not for all the people." Of the 1,500 who were supposed to go to the Tulalip reservation, only 165 Indians had land allotted to them, according to a 1977 congressional report. The rest chose to leave for a variety of reasons, according to the report, including uninhabitable land and fear of being attacked by other hostile Indians from up the coast. In 1979, the landless tribe petitioned the Bureau of Indian Affairs for federal recognition. Later that year, things went from bad to worse for the tribe. U.S. District Judge George Boldt, in his final decision as a jurist before retiring with Alzheimer's disease, ruled that five tribes -- including the Snohomish -- were extinct as a people and had no treaty fishing rights. "We couldn't believe it," says Kidder. "It was like a part of me was taken away. "I felt terrible." More than two decades later, the Bureau of Indian Affairs has yet to finally resolve the case, and the tribe remains in legal limbo. Part of the problem is that the Tulalip tribes contend that they are the true successors of the historic Snohomish tribe. Many people on the Tulalip reservation have Snohomish blood. Without a reservation, treaty fishing rights and federal support for health care, economic development, housing, social services and cultural activities, the Snohomish have struggled to hold the tribe together. Even though many Snohomish people have scattered away from around the river that bears their name, there are still more than 1,600 enrolled members, said tribal Chairman Bill Matheson. He says an official with the Bureau of Indian Affairs told him the Snohomish Tribe tops the active consideration list for tribal recognition. Matheson hopes to get an answer from the BIA this year. But he's heard such promises before. "I'm trying to hold an unrecognized tribe together with no land base," Matheson says. "We don't have any government benefits that would help us with education, health care or renewing our culture and language. Our people are on their own."

You are extinct as a people, the agency ruled. "It's a never-ending story for us," says Ortez, the tribe's chairwoman, while sitting in the Steilacoom Tribal Cultural Center in the Puget Sound village named after the tribe. The decision, though preliminary, was devastating to the tribe's nearly 700 members. The Snohomish was one of several tribes that signed the Medicine Creek Treaty in 1854, an agreement with the U.S. government that, among other things, guaranteed them a place to live. But only three of the tribes that signed the treaty got reservations. Steilacoom was not one of them. "In 1972, we wrote to the president, but got no answer," says Ortez, whose grandmother was a full-blood Indian born at the Hudson Bay Co. trading post in Dupont called Fort Nisqually. "She always said she married my grandfather because he wanted a young, strong Indian maiden to raise a lot of sons and help him run his ranch," says Ortez, 66. Her grandmother, Hotesa, as she was called in the Salish language, smoked and dried salmon and cooked the traditional foods, such as clams in baskets heated with hot rocks. At the time, many Steilacoom people were living in what is now the North Fort Lewis area, in little shacks in the berry fields of Puyallup or the hops fields around Roy. Traveling with their old uncle, Lou, the children would visit the Indian people on Squaxin Island. "We'd eat deer, clams and salmon with them. We'd dig clams on the beach," Ortez says. "We'd go in the canoe to his favorite fresh-water spring and haul (water) back to the cabin. It was so fresh and cold."Ortez learned tribal political activism at her mother's knee. Her mother served on the council for 25 years until her death in 1977. "She talked about holding the tribe together, the survival of the tribe." That could prove to be a daunting task At the semi-annual general membership meetings, attendance ranges from the "low 20s to 30s," Ortez says. Perhaps the biggest impediment to tribal survival is the way individual Steilacooms have learned to cope with the world. "There's a lot of them out there that know that they're Steilacoom but don't really participate in what the tribe offers," she says. "In order for them to survive, they've had to be like their neighbor and work in the labor force. But behind closed doors, a lot of them are doing traditional things."Ortez has passed on to her 44-year-old son Danny Marshall the desire to serve the tribe. That helps explain why Marshall has been on the tribal council for 23 years. His frustration at dealing with the painfully slow process of gaining federal recognition is palpable. Talking about that process spurred him to tell this story: In the early days of the last century, the family lived on his great-grandfather's ranch. Then the Army decided to build Fort Lewis. They drew cannons up to the house to force the family to leave. And when they finally got out of the house, the Army put guards there to keep them from coming back. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

Chevalier

of Friday Harbor says he doesn't think of himself as Indian, yet some

practices of native ancestors from the San Juan Tribe are simply a part

of life for him. Mike Urban / Seattle Post-Intelligencer

Chevalier

of Friday Harbor says he doesn't think of himself as Indian, yet some

practices of native ancestors from the San Juan Tribe are simply a part

of life for him. Mike Urban / Seattle Post-Intelligencer Standing

at the helm of his skiff as it bounces on the waves, he heads toward

the Stuart Island home of his 94-year-old aunt, Caroline Mills.

Standing

at the helm of his skiff as it bounces on the waves, he heads toward

the Stuart Island home of his 94-year-old aunt, Caroline Mills. "When

I grew up here, there were salmon jumping onto the dock," he says.

"There was herring in this bay so thick we could go down and jig

them."

"When

I grew up here, there were salmon jumping onto the dock," he says.

"There was herring in this bay so thick we could go down and jig

them."