|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

July 13, 2002 - Issue 65 |

||

|

|

||

|

In Old Names, a Legacy Reclaimed |

||

|

by DeNeen L. Brown Washington

Post Foreign Service

|

||

|

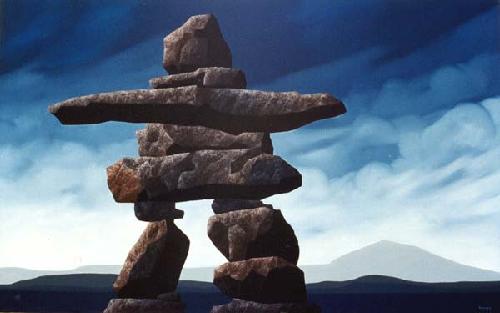

credits: art This

is Nunavut by Ken Kirkby

|

IQALUIT,

Nunavut -- When the missionaries came north to this frozen land of blizzards

and deserts, they could not understand why the people they met, the

Inuit, had no last names. Why some men carried the names of female ancestors.

Why some women carried the names of their uncles, why a little boy might

call his father "my son." Why a grandfather might call his

infant granddaughter "my sweet little mother." IQALUIT,

Nunavut -- When the missionaries came north to this frozen land of blizzards

and deserts, they could not understand why the people they met, the

Inuit, had no last names. Why some men carried the names of female ancestors.

Why some women carried the names of their uncles, why a little boy might

call his father "my son." Why a grandfather might call his

infant granddaughter "my sweet little mother."

None of this made sense to the people who came north believing that the Inuit needed to be saved, brought in from the killing wilderness and placed in artificial communities. So the missionaries and government workers set about "correcting" a social system that had been in place for thousands of years. Government practices required that the Inuit be sorted into a bureaucratic system that would provide some accountability. So, they were first given numbers, to be worn on tags around their necks, people here recall. Later, they were told to take surnames. And as they were moved into towns, they were discouraged from practicing their religion and culture, according to interviews and government documents. Now, decades after this infiltration, the Inuit are reclaiming much of what was lost, including their names. Hundreds of Inuit in the new territory of Nunavut are going to court to correct old misspellings and to finally, officially cast off the numbers. It is more than symbolic, people here say. For many, it is an act of reclaiming an identity that was nearly wiped out. "Names are a very important part of Inuit culture. Every name has a definition," said Peter Irniq, the commissioner of Nunavut. "We take back our culture and our names." Traditional Inuit names reflect all aspects of what is important in Inuit culture: environment, landscape, kinship, animals and birds, spirits. "People could have a name like Tulugaq, for raven," said Irniq, whose name means son. "A lot of people are named Nauja, for sea gull. A lot of people are named Amaruq, wolf." Others are named after seals or caribou. A lot of names start with Arnaq, which is the root word for woman. Men can use that name, too, but would add an action word to it to make "Arnauyq," which translates as "imitation of woman." Some people are named after the sky, others after spirits. "Some people could have the name Arnaaluk, which is the spirit name of a group of Inuit from a particular region, meaning a big woman, a spirit of the woman under the sea," Irniq said. Such a woman is prominent in Inuit mythology. And some people are named after body parts. Taliriktug, for instance -- strong arm. In traditional society, the Inuit believed that spirits of the dead continued to live. Newborns were often named after a dead person, and treated as if they possessed the spirit of the one who was gone; they were addressed as "mother" or "father," as the departed person had been. Those children who were named after elders were revered. They were never spanked. They were spoken to softly and fed well, as if they were the elders who had come before them. Children could receive many names in a lifetime. When a child cried too much, it meant a dead person wanted the child to have his or her name. "There was one child, whose grandfather had died after the child was born," recalled Rachel Uyarasuk in "Inuit Perspectives of the 20th Century," a compilation of interviews with elders. "The baby became sick. When I went there, I was told that I was to bestow the name on the child." Uyarasuk said she was very nervous about being given this great responsibility. The next day she went to the house again and learned that "the person that the baby was to be named after had had difficulty walking," she said. "So I said to the sick child that I wanted the child to be that person [but] that the child would have no difficulty running after things. I told the child he was going to get better, and that after he learned to walk, when he became able to, he was to run. . . . The child became better and never got sick like that again." If a pregnant woman dreamed about a dead person, it was said that the dead person wanted the baby to have his or her name. People were said to receive power from their names, especially if they were named after a shaman, an angakkuq, which means a very wise person, some of whom see the invisible and hear what others cannot hear. "We name people so that the deceased may live forever," Irniq said. His mother, for instance, named three children after his father. All of this was confusing to the people who arrived from the south. So in the early 1920s, they decided that each Inuit needed an identity that the government could understand. They passed out numbers, carved on dog tags. Most of the numbers began with the letter E, meaning East. From that day forward, each Inuit would carry what they called an "Eskimo" number. They were told to keep the numbers tied around their necks, to not get the tags dirty or lose them. For some, those numbers with those leather strings became seared in their minds. Akaka Sataa recalled the day government workers appeared in his community and counted the people there. He was the 37th person they pointed to. "When they got to me, they gave me number E7-37," said Sataa, who was born on the land outside the community of Kimmirut 84 years ago. It was a curious tag. He rubbed the numbers smooth, and wore it. "We accepted everything the qallunaat [non-Inuit] told us to do," he said. Eva Aariak, languages commissioner of Nunavut, also acquired an E number early in her life. "It was part of me," she recalled. "I know my mother's number and father's number. We used to compare numbers." At the same time, missionaries were establishing churches and the Christian religion in the north. The Inuit were often made to feel guilty for believing in shamanism, people here say; many took Christian first names to show they had put those beliefs behind them. In the 1970s, the Canadian government issued a new order. Officials went to every part of the Arctic to decree that people adopt surnames, which were not part of the Inuit tradition. The drive became known as Project Surname, and prompted confusion and resentment. Many of the E numbers were thrown out as people took last names. But the government workers, many of whom did not speak the local language, Inuktitut, often rendered the names in spellings that had little to do with actual pronunciation. "They would spell it in the way they heard the language," said Aariak, whose name was once written as Arreak. "The spellings were atrocious. But they couldn't get help from people who held the names because they didn't spell in English. Our language is very phonetic." In Inuktitut, there are no sounds for e, b or w, and yet those letters show up in many names as rendered years ago by people from the south. "When I was born, a priest spelled my name Ernick," said Irniq. "I was never proud of Ernik or Erneck," other variations that were used. Aariak had a similar experience. She was originally named after her mother's sister. "I never liked the spelling of Kamanirk," which was how the missionaries rendered it, she said. "It's Qamaniq." Things began to change with the April 1, 1999, establishment of the Nunavut territory, an 800,000-square-mile expanse in Canada's far north. The Inuit became one of the first indigenous people to retrieve territory based on ancient claims. With it came a sense of renewed pride. Nunavut, the first territory to enter Canada's federation since Newfoundland joined in 1949, literally changed the map of Canada. Its capital is a frontier town with about 6,200 people. It is a town without streetlights or street signs, but with several banks, stores, taxis and rows and rows of government buildings. It is a strange mixture of the modern and the ancient, with four-wheel drives and dog sleds. It was once called Frobisher Bay; now it's Iqaluit, which means fishes. At the Nunavut Court of Justice, names are being changed, too. About 400 people throughout the territory have done so. The court processes the requests for free, in recognition that the government shouldn't exact a fee to correct a problem it created. "It's taking back and anchoring the language and the name," said Aariak, as she sat in her office in Iqaluit. A blizzard outside was carrying a cold so intense that a walk across the parking lot could make the fingers go numb. "It's part of regaining pride in the culture. It was a sense for not just taking whatever we've been given." Shani Watts, Nunavut Court of Justice administrator, said many of the people coming to the court simply wanted to get rid of E numbers that are still listed on government papers. People who have Christian names have generally kept them, and there's been no movement to drop surnames. What many people who come to the court want to change is the official spelling of those surnames, to something that sounds right to the Inuit ear. "The Inuit were degraded," Aariak said. "The missionaries never thought to understand the existing culture. But whatever they ordered, the Inuit felt they had to follow. . . . You were taught to listen to elders, listen to adults. These guys coming were adults." From the outside, the Inuit appeared to change. "But deep down in each person," Aariak said, "they never really changed." |

|

|

||

| Our great ccna pdf test have great selection, make the recipient feel extra special, for the memory and the uniqueness of it. We designed sat prep courses practice test, gmat questions practice questions along with ged exam for different purposes like style, fashion and especially for ease. Our act practice test. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||