|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

June 29, 2002 - Issue 64 |

||

|

|

||

|

Tribe Strives to Pass on Wampanoag Culture |

||

|

by Sean Gonsalves Cape

Code Online

|

||

|

credits:The Mashpee

Wampanoag helped the Mashantucket Pequots build authentic wetus, or

domed cedar huts, in an exhibit at a museum adjacent to Foxwoods casino

in Ledyard, Conn. (Staff photo by Kevin Mingora)

|

MASHPEE,

MA - When the Mashantucket Pequots opened the largest Native American

museum in the country four years ago, they called on the Mashpee Wampanoag

for help. MASHPEE,

MA - When the Mashantucket Pequots opened the largest Native American

museum in the country four years ago, they called on the Mashpee Wampanoag

for help.

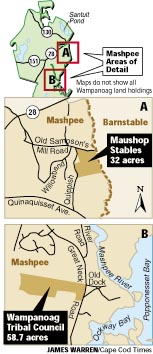

The museum next door to the tribe's Foxwoods Resort Casino in Ledyard, Conn., provides a trip through time, tracing the Pequot history from the last Ice Age to the present. The centerpiece of a replica half-acre village is comprised of three wetus - domed cedar huts that northeastern Indians built for temporary family shelters as they roamed the wooded coast, fishing and hunting. A pictorial display and video-monitor demonstrate how. Mashpee Wampanoag members Russell Peters Jr., Annawon Weeden and Darius Coombs constructed them. Linda Coombs of the Aquinnah Wampanaog tribe on Martha's Vineyard collected and prepared the bulrush reeds used to bind the bark and poles together, and weave together the wetu floor mats. "What they lost was not their fault," Darius Coombs said about the Pequot. "So it's great to help them recover what they've lost." He said he learned the traditional Wampanoag ways both orally and through the written record, crediting Wampanoag such as the late Nanepashemet and the late Helen Attaquin. Both he and Linda Coombs, his sister-in-law, work at Plimoth Plantation in Plymouth, where they interpret 17th-century Wampanoag culture for visitors. Ironic reminder In fact, the Mashpee Wampanoag's know-how and practice of traditional ways has been tapped by other area tribes, including those who have been federally recognized for years. "We worked closely with a number of the Mashpee tribal members when constructing the exhibits in the museum, and we used some of their cultural consultants as well," said Pequot Tribal Council Chairman Kenneth Reels. Building wetus at the Pequot museum isn't the only cultural exchange shared between the federally-recognized Pequots and the yet-to-be recognized Mashpee Wampanoag. "We have been honored in the past to have Slow Turtle (John Peters) conduct ceremonies and blessings on our reservation," Reels said. "We also encourage people to read books written by the Mashpee people to get an authentic representation of native life in the region. Many recognize the knowledge contained in the Mashpee community," he said. "When people want to know about the history of Cape Cod, they contact the Mashpee (Wampanoag). People look to them for their knowledge of the rich history of the Mashpee region," he said. Other cultural traditions link the Mashpee Wampanoag to their past. The tribe's Red Hawk singers keep alive native singing and drumming. Reviving the language The project is run by a committee made up of Mashpee Wampanoag, Aquinnah Wampanoag on Martha's Vineyard, and members of the Assonet tribe in Freetown near New Bedford. Fermino began teaching an introductory course in 1998 once a week. Now, with the help of a paid assistant and financial support from a local Quaker group, Fermino teaches three courses each week in Mashpee and on Martha's Vineyard for tribe members only, including a more advanced "immersion" course in which English is prohibited. Fermino is also compiling a Wampanoag dictionary. And it's not just Wampanoag who are learning about their native tongue. Melanie Rodrick, a 23-year-old member of the Assonet tribe, says learning the language of her ancestors is empowering. "It seems like something that should be done. It makes me proud to be able to speak something that is our own." Struggle for recognition Wright, whose tribe was federally recognized in 1987, considers the Mashpees a sister-tribe that has maintained its identity from before 1620, when the Pilgrims first arrived on Cape Cod shores, until now. "It's not: 'On this special day, we are going to be Mashpee Wampanoag.' They are Mashpee Wampanoag every day," she said. "I think most tribes are that way, but because there are so few Indian nations on the East Coast, the Mashpees practicing their culture and tradition every day seems to be special." Reels agrees, which is why his Pequot tribe is supportive of the Mashpee Wampanoag petition for federal recognition. "When it comes time for the Mashpee Nation's struggle for recognition of their rights as indigenous people and an opportunity to become self-sufficient, those same people who turned to them for knowledge in the past have the opportunity to be advocates for them in this arena also." Mashpee Wampanoag: a history

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

The

wetus in the Pequot museum stand as an ironic reminder that, although

they have yet to be recognized as an authentic, historic tribe of Indians

by the federal government, the Mashpee Wampanoag are a wellspring of

knowledge when it comes to traditional Indian culture and ways of life.

The

wetus in the Pequot museum stand as an ironic reminder that, although

they have yet to be recognized as an authentic, historic tribe of Indians

by the federal government, the Mashpee Wampanoag are a wellspring of

knowledge when it comes to traditional Indian culture and ways of life.