|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

June 15, 2002 - Issue 63 |

||

|

|

||

|

Native American Leaders Celebrated by the Ford Foundation |

||

|

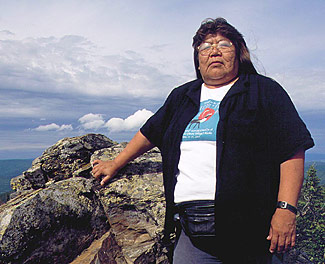

credits:Photo of

Sarah by James H. Barker Photo of Denise by Jared Leeds

|

|

The Ford Foundation recently recognized community leaders for outstanding leadership. We salute these two Native American women who are making a difference:

An indigenous people fight to protect their culture on Alaska's coastal plain. The challenge The winds of commitment Accomplishments James brings people from all over the world to Arctic Village and the Gwich'in villages to meet the Caribou People and better understand their way of life. She has traveled far to bring the story of her people to the world, speaking in many countries about indigenous rights, human rights, and environmental issues. To share the Gwich'in's message, she has performed caribou drum and traditional songs at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in New York City and at the first "Earth Summit" in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. She has been a keynote speaker at conferences and symposia around the world and has provided testimony to both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. She is a board member of the International Indian Treaty Council, a national representative for the Council of Athabascan Tribal Governments, a special advisor to the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council and a member of the indigenous people subcommittee of the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency's National Environmental Justice Advisory Council. She has educated the Gwich'in about bioaccumulation of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), especially in cold artic regions, and how this disproportionately affects indigenous people who consume large amounts of fish and meat. She mentored a young, well-educated man from her community, who eventually attended United Nations-sponsored international treaty negotiations for the elimination of POPs. He is now a statewide spokesperson and organizer on the issue. As a spokesperson and alliance-builder, she has worked with Arctic Village and neighboring Venetie to reduce their dependence on fossil fuels and strengthen their traditional culture by using renewable resources such as wind and solar power. (In remote communities, electricity is produced with diesel fuel and generators.) In the summer of 2001, this vision became a reality with the installation of solar panels that produce power in the two communities. "This is the start of creating our own energy independence, of walking the walk," she says. Sarah James has also launched an effort to create a community radio station powered by renewable energy. It will broadcast conventionally over the airwaves, and also on the Internet – in her people's indigenous language as well as in English. She has already secured $152,000 for the project, and has involved her entire community in the effort. This use of technology, she believes, will help preserve her people's language and traditions. And then many Gwich'in voices will reach around the globe – speaking for the caribou, for the kind of energy independence that preserves nature, and for a way of life. How she leads The future More about Sarah James

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A Maine woman helps Native youth reclaim their past and future. The challenge Seeds of commitment Achievements While young people are primary constituents of the Wabanaki Youth Program, Denise's work improves the lives of entire communities. Some recent examples: • Altvater and other Wabanaki adults who had been placed in foster homes as children helped train more than 500 Maine Department of Human Services workers in how to comply with a 1978 federal law designed to reduce the high number of native children being sent to live with non-native families. The training included education in Wabanaki culture and methods of keeping native children within their communities. • She is one of the primary organizers of an annual Youth Wellness Institute and helped create the Wabanaki Youth Alliance, which trains youths from each community in topics chosen by the young people: internalized repression, racism, suicide prevention and sexuality. •Altvater and Wabanaki youth leaders helped organize the National A.F.S.C. Indigenous Youth Gathering held in August, 2000 in Lake Tahoe, Calif. • She helped Wabanaki youth leaders design projects aimed at challenging homophobia in the community. • To combat school violence and racism against native youths, Altvater developed cultural exchanges among schools in the Northeastern United States. • She provided anti-racism and cutural training for Washington County jail guards. • She was one of six founders of Silent Cry, a group for sexual abuse survivors, which transformed itself into an activist group called Screaming Eagle. • In March, she helped organize the Indigenous Women's Voices Gathering at the University of Southern Maine, a ground-breaking event providing women and girls with the opportunity to learn, drum and sing. Her leadership style The future More about Denise Altvater and the

Wabanaki

|

||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

Local

and Global Leadership, Gwich'in Style: Sarah James

Local

and Global Leadership, Gwich'in Style: Sarah James

People

of the Dawn: Denise Altvater

People

of the Dawn: Denise Altvater