|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

April 20, 2002 - Issue 59 |

||

|

|

||

|

Institute Bringing Blackfeet Language Into Next Century |

||

|

by Karen Ivanova

Great Falls Tribune

Regional Editor

|

||

|

credits:

by Stuart S. White

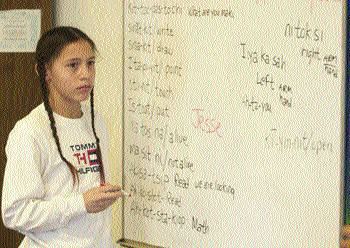

Jesse Des Rosier, 13, listens to a teacher's instructions in Piegan. Jesse joined his little brother at the Nizipuh-wahsin lang-uage school four years ago because he liked the flag football team. Now one of the school's most fluent Piegan speakers, Jesse says he's learned important lessons. "They teach you a lot of respect in the school for elders," he said. |

|

He orders classmates to draw a picture of their school on the grease board, to pick up a toy truck from an assortment of items on the floor, to shake his hand. A lanky teen-ager with long black braids, a mouthful of braces and a Tommy Hilfiger T-shirt, Jesse is the face of a renaissance in Indian Country. He and his 30-some classmates at the Nizipuhwahsin Center, a private school on the Blackfeet Reservation, take all of their classes in their native language. From math to biology they study in "Piegan," the Blackfeet's original, or "nizipuhwahsin," language. Their teachers want to produce the first new generation of Piegan speakers in decades. Jesse and his peers are the Blackfeet's best hope to save their fading language, of which only roughly 500 fluent, mostly elderly speakers remain. "The greatest thing about this school is that my children, including all the kids at the Nizipuhwahsin Center, are bringing the language into the next century," said Jesse's mother, Joycelyn Des Rosier. "Now it won't die." The Nizipuhwahsin Center was founded in 1995 in Browning as a "language immersion" pre-school program. It has since added a second, $500,000 complex. Three sunny classrooms house preschool, elementary and middle school programs. Jane Fonda gave the first $100,000 for the new building, finished in 2000. Tuition is moderate for a private school at $100 a month. About 20 percent of the students are on scholarship. The curriculum is unconventional. There are no grade levels and students often don't start writing until they're 7 or 8 years old. English grammar lessons don't start until age 11 or so. "It does rattle parents when they worry that children aren't receiving formal reading," said Darrell Robes Kipp, executive director of the Piegan Institute, the Blackfeet language preservation group that founded Nizipuhwahsin. The school's philosophy is rooted in research showing that children educated in two languages perform better in school than those who speak only one. "You take something as old as your language and you couple it with a high academic system and you produce these extremely healthy children," Kipp said. In Hawaii's footsteps Crow Shoe, 48, quizzes her elementary-age class on the days of January in Piegan. Later, she moves on to shapes, asking the students to name circles, triangles and rectangles -- "isinapimoyi" -- in Piegan. "Oh, man!" a boy stumped on a question says under his breath. English is not allowed here. Nizipuhwahsin is modeled after a language "nest" school started on the Hawaiian Island of Kauai. At that time, fewer than 50 children under the age of 18 were fluent Hawaiian speakers. Today the "Aha Punana Leo" organization operates nest preschools across the islands in addition to three K-12 schools. The program graduated its first K-12 class in 1999. Roughly 2,000 Hawaiian kids attend "Aha Punana Leo" schools or similar language immersion centers established in cooperation with the state. Kipp, a 57-year-old Harvard graduate and former technical writer, helped found the Nizipuhwahsin Center after visiting Hawaii with a group of 35 Blackfeet. "They were the ones that really illustrated the impacts of language revitalization among indigenous people," he said. Hawaiians who know their language can "go out in the world and know who they are," said Niniau Kawaihae, outreach coordinator for the College of Hawaiian Language at the University of Hawaii-Hilo. "They're not searching for their roots and searching for something to satisfy them internally." Kawaihae was hired last September, under a grant from the Ford Foundation, to coordinate tours of the college and the "Aha Punana Leo" schools. So many curious tribal groups and journalists from the mainland were visiting that professors couldn't tend to their work. Sink or swim Rainy Kipp, a distant relative of Darrell Kipp's, is one of Nizipuhwahsin's three eighth-grade graduates. A fourth will graduate this spring. She started treading water in Piegan during her first few weeks at the Nizipuhwahsin school when she was 12 years old. A teacher encouraged her to write down the words she could understand each day and helped her fill in the blanks. Students practice through the "total physical response" method, meaning they act out Piegan phrases as they learn them. Classes are multi-age so that older or more experienced students can pull younger kids or new students along. "Everybody treated everybody with respect and the teachers and everything," Kipp said of her years at Nizipuhwahsin. "There was no talking back." Now 15, Kipp is in the ninth grade at Heart Butte High School where she made the honor roll last fall. A ranch girl at heart, she plans to become a veterinarian. "I miss (Nizipuhwahsin) a lot," she said. "I wish I could go back." Teachers fluent Ed Little Plume, 65, is a Nizipuhwahsin founder and master teacher. A lifelong rancher, he's considered one of the reservation's most fluent Piegan speakers. He is state certified to teach Piegan. Arthur West Wolf, 47, worked 15 years as a teacher's aid in the Browning Public Schools. He recently earned his teaching degree from the University of Great Falls and also is state certified. Crow Shoe is a member of the North Peigan Tribe of Blackfoot in Canada, which is spelled differently than the language and the institute in the United States. She taught her language for 15 years in the Canadian public school system before moving to Browning. She remembers her grandmother telling bedtime stories in her native language. "I knew when my grandmother was falling asleep because she would say something wrong and I'd tell her, 'No Grandmother, you're telling it wrong.'" Growing up on the North Peigan Reserve, Crow Shoe never imagined that she would one day have to teach her language and culture -- knowledge she soaked up at her grandmother's side -- in a classroom. "I always took it for granted that what I knew, everyone else knew," she said. Crow Shoe met Darrell Kipp and learned of the Nizipuhwahsin effort at a 1995 powwow in Browning. "He only gave us one directive and that directive was teach the Blackfeet language," she said. Lessons challenging Jesse calls Michael "Neskun," the Piegan term an older brother calls his younger brother. Michael calls Jesse "Nissa," meaning older brother. Objects summed up with one noun in the English language may require a short phrase in Piegan. Especially new words such as "radio," described in Piegan as "spirits that tell you the news," Des Rosier explains. First attracted to the school's flag football team, Des Rosier said he's learned important lessons here about respect for elders. "I like learning about our history," he added. "But sometimes I get mad." History, which has included some brutal chapters for the Blackfeet in the last century, is an important part of the curriculum, Kipp said. "We want these children to be knowledgeable about themselves, their family histories, their tribal histories," Kipp said. Joycelyn Des Rosier admits she had concerns about Nizipuhwahsin's non-traditional curriculum. "I used to worry, 'Oh my God, my kids are going to be so behind, they're never going to know anything,'" she said. Her worries eased last fall when she saw Rainy Kipp's success at Heart Butte High School. Though students start formal English lessons later at Nizipuhwahsin, they learn fast because they're already familiar with the grammatical structures of two languages, Darrell Kipp said. By sixth grade, students study geometry, algebra and botany in Piegan. The new speakers "We know how important our language is as a people," said Helen Horn, whose 10-year-old son, Keith, attends Nizipuhwahsin. "If we lose that, we lose our identity and what makes us different from every other Native American. Our culture, our, traditions -- everything -- our history, it's all in our language." With that identity comes confidence that helps kids avoid the drugs, early dropout rates and teen pregnancies that often snare children on the reservation, Kipp said. Horn took two Piegan classes at the local community college so she can speak with her kids at home. "I didn't know what my kids were saying sometimes," she said. "They'd all be talking to me at once in Blackfeet." But she pulled her two daughters, Larissa, 8, and Shanell, 6, out of Nizipuhwahsin for this school year. Shanell wanted to go to kindergarten like a neighbor girl, and Larissa decided to go to public school with her, Horn said. Larissa started second grade last fall at a kindergarten reading level, but tested at second-grade level for the first time last week. "She's in the top part of her class now," Horn said. "She's really come a long ways and I credit a lot of that to teaching them in the immersion school that there's no barriers to what they can learn." For Nizipuhwahsin to succeed in saving the language, the students must succeed in their own lives, the educators say. "One of the ways to revitalize a language is to put status into it," Darrell Kipp said. "Any Blackfeet who will be able to speak our language fluently in 2005 will be indeed an outstanding and respected individual because it will be very rare to find such an individual." Most fluent Piegan speakers are in their 80s. "For all purposes at this stage they're homebound," Kipp said. "It's a real special occasion when they come out to a tribal ceremony or something. They're highly venerated." Already, Nizipuhwahsin students are being asked to pray or give introductions at tribal ceremonies. "These children ... in the next three or four years as they achieve adult status, even very young adult status, they're the ones that are going to be asked to get up and do these things," Kipp said. Not a government nickel Nizipuhwahsin has cost $2.8 million since it started seven years ago. "There's not a government nickel in this place," Kipp said. The Lannan Foundation, a private family foundation from Santa Fe, N.M., contributed close to $1.7 million. The W.K. Kellogg Foundation and Howard Terpning, a Western artist, also are major sponsors. The Piegan Institute recently established an endowment fund to support the school. So far they've raised $100,000. The goal is $2 million over the next two years. It's a long-term investment. Even in Hawaii, where language immersion schools are nearly 20 years old, it's too early to say the language is saved. The nest schools' oldest graduates are 21. They will need to raise their own families in Hawaiian-speaking homes before the language takes permanent root. "We don't have measurable results," said Aha Punana Leo spokeswoman Luahiwa Namahoe. "We're still running on faith until the majority of the (students') parents are graduates themselves." Ultimately, success won't be measured in the classroom. "The best way to measure it is to see kids playing dodge ball in Hawaiian. To see people arguing in Hawaiian or cracking jokes in Hawaiian," Namahoe said. Time will tell Kipp is counting on students like Jesse and Michael to return to the reservation one day to run the Nizipuhwahsin center. "Time will tell the effectiveness of this model," he said. Kipp views the Piegan language as an endangered species. In the same way plants in the rainforest may carry cures to diseases, the language carries lessons and history that could be lost forever. "Languages, just like other species, carry some secrets in them that we don't know about," Kipp said. "Inside the language are all the secrets of our tribe." |

|

|

|

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

BROWNING

-- Thirteen-year-old Jesse Des Rosier is the picture of confidence

as he calls out commands in Blackfeet.

BROWNING

-- Thirteen-year-old Jesse Des Rosier is the picture of confidence

as he calls out commands in Blackfeet.