|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

April 6, 2002 - Issue 58 |

||

|

|

||

|

'Dreaming' a Language Back to Life |

||

|

by Gail Ellen Daly Norwich

Bulletin

|

||

|

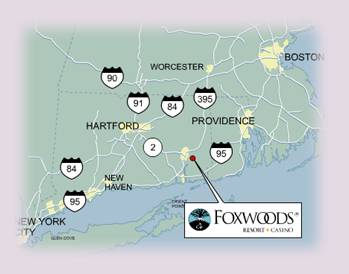

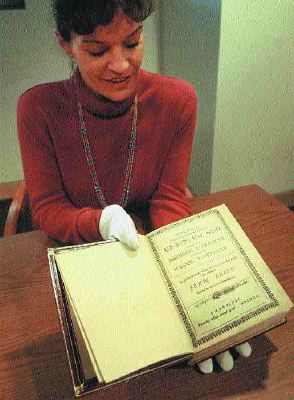

credits: John Shishmanian

Norwich Bulletin/Charlene Jones, uses protective gloves to hold

the 1685 Holy Bible translated into the Massachusett Indian language

|

On

the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation, in the brightly colored Child Development

Center, words are being uttered that haven't been heard in hundreds of

years. On

the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation, in the brightly colored Child Development

Center, words are being uttered that haven't been heard in hundreds of

years.

To the children in the tribe's development center, it is simply the "Flag Song." But these children are a link to the tribe's past, to its culture, to its language. The simple song about honoring a flag was developed with the few words the Pequots have recovered so far and has been put on tape. "I'm so proud when I hear the children at the Development Center singing," said Charlene Jones, a member of the Pequot Tribal Council who is spearheading the effort to retrieve lost Indian languages. "They have a greater understanding of who they are and every parent becomes emotional." At this point, the words are not written, just spoken. Jones said Friday, however, that Indian lawyer Gerald Hill, who works with the Indigenous Language Institute in New Mexico, has begun helping her committee write a planning grant to assess the "interest and commitment" of tribal members and non-tribal members in continuing the project. Most people take language for granted. But for the Pequots, recreating their all but extinct tongue is a way to regain a sense of identity and secure the tribe's culture. "We're breathing life into the Pequot language," she said. The Pequots are not alone. The Passamaquoddy Language Program in eastern Maine has been renewed, with several tribal members able to speak the language fluently. Linguist Jessie Little Doe Fermino, a Mashpee Wampanoag who gained a fellowship at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, began the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project in 1993. "Language is the soul of a nation," said Chief Oren Lyons of the Onondaga Nation. "It is the cornerstone of culture." A long process "It's like watching slow motion," he said. Whalen, president of the New Haven-based Endangered Language Fund at Yale University's Department of Linguists, is also the founder of the program that in the last five years has funded 53 language revitalization projects. "Language is a big part of the cultural identity of native peoples and can have a big impact on the people's lives," he said. "When a language is gone, it's gone forever." The fund is a program that supports ongoing projects all over the world. Whalen noted, for example, that Cornish, spoken in the English section of Cornwall, disappeared in the early 20th century. It is now being revived, but since the language is related to Gaelic and Welsh, the revival is easier. Jones believes language is a major piece of the tribe's culture. "Personally, and for the tribe, language gives people a better understanding of themselves," she said. "Our culture wants to survive and language completes the circle. It gives us a sense of self." Fragments endure Growing up on the reservation, she recalled, even her family could only speak a few fragmented words. Outlawed by the 1638 Treaty of Hartford, her native language may not have been spoken in hundreds of years. Fortunately for those involved in its recreation, much written documentation remains. Early missionaries who worked to convert native people to Christianity needed to learn the native languages. They intermarried, thus learning each other's languages. A diary by Ezra Stiles of Yale University dates from the late 1700s and even contains written conversations. He made notes stating the people spoke with "guttural sounds." John Eliot's Bible is a complete translation of the Old and New Testaments into Massachusett. The first edition, printed at Harvard University in 1663, was the first Bible printed in the New World. A young Nipmuck named James assisted Eliot. When the copies were destroyed during King Phillip's War, Joseph resumed his printing duties in Cambridge, with the priority of printing a second edition of Eliot's Bible. In 1933, 64 copies of the second edition were still in existence. Today only three remain. The pristine copy at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center sold at Christy's Auction House a number of years ago for $285,000. The museum's acquisition department paid "something more than" $50,000 for the copy. Jones believes that one copy is at Plimouth Plantation and the third in the British Museum of Mankind. "But the translation loses part of the meaning," she said. "It loses some of the uniqueness and -- after such a long break -- dialect becomes difficult." Place names are listed on old cartographer's maps, although the names were subject to the cartographer's interpretation. The Pequots are one of two local tribes using Eliot's Bible as a guide to language revitalization. Compare notes "We start with what's recorded," she said, "including Eliot." She noted that much came from Fidelia Fielding's diaries, which contained some of the language. Fielding, the last fluent Mohegan speaker, died in 1908. The first step is to look at neighboring Algonquian languages, which contain many similarities. "If there is no word in Mohegan," she said, "we look at the closest geographical place where the word exists -- especially the Narragansett and Wampanoag language." Starting with a basic number of words, it then becomes possible to have a conversation. Hamilton said the tribe is currently at that point. Interactive CDs are being recorded, which should be completed by next year. 'Awakening' a process Western tribes still retain their language. However, said Jon Reyhner, an associate professor at Northern Arizona University, only tribes in New Mexico, Arizona and Montana have had their language handed down through the generations. In "awakening languages," Reyhner suggests a number of successful approaches: Use teams of dedicated people. Use immersion speaking as much as possible. Set goals. Build up, not out, by using vocabulary and work through language variation issues. He said the three Ms are methodology, materials and motivation. "Bring back songs and greetings," Reyhner said, as they are the culture which should never be lost. Jones agreed that Pequot would primarily be spoken at ceremonial events and songs. Pequot is part of the Algonquian language group, which means that all words have similar roots, much as the Romance languages have similar roots. The Seneca tribe of western New York, for example, is part of the Iroquois language group. Daryl Baldwin, a member of the Miami Tribe of Indiana, Ohio and Illinois and director of the Miami Project, said his language was fragmented and fell dormant during a short span of 100 years. The effort to reclaim Miami began in 1995. As part of the Miami Project, Whalen said, children are spoken to only in Miami. Baldwin called reclamation a community issue that can only succeed with the support and participation of the community. Hamilton pointed out that her tribe is using the same method as the Miami tribe. "It's a disadvantage not having speakers, but we have none, so no one alive knows what Mohegan sounded like." Nevertheless, she believes that they have done a remarkable job in a short period of time. Whalen believes when the Pequot project is complete, it will be as real as possible under the circumstances, as there is much that has been reasonably well recorded. Jones is convinced the Pequot language can be revived. "Within five years, with diligent research, we should have a dictionary," she said. Verbal communication would be primarily for ceremonial use. Eventually, a curriculum to teach children the language would be developed. All Indian papers are being transcribed with the Tribal Council's blessing. "We're fortunate that Foxwoods' success has afforded us the means to do this -- to have the research center," Jones said. "This is my lifelong dream and I've lived to see it come to this point." Recognizable roots The new and old testaments of the Bible translated into Massachusset - Mamusse wunneetupanatamwe up - Biblum God naneeswe nukkone testament kah wonk wusku testament. Examples of Native languages using root words:

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||