|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

March 9, 2002 - Issue 56 |

||

|

|

||

|

Elders Seek Way to Preserve Fading Language |

||

|

by William Yardley The

Miami Herald

|

||

|

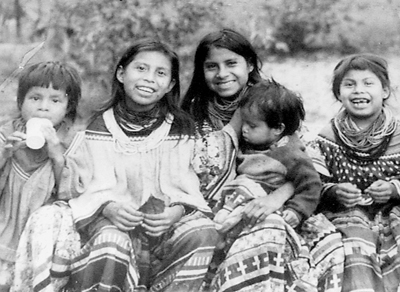

Jason Wromas. Young Miccosukee children

dress in traditional wear and await their next day in school. A luxury

that their father Buffalo Tiger once could not enjoy.

|

|

But for all of the secular success the Miccosukee Indians have enjoyed from their flourishing capitalist pursuits in recent years, one ancient investment is no longer a sure bet. The Miccosukee language, the only one that some tribal elders speak fluently, is becoming an endangered cultural species among tribal youth -- a victim rather than a victor in the tribe's increasing encounters with mainstream America. Indigenous languages are declining worldwide, but the decline among the Miccosukees is particularly striking because the tribe -- which still considers itself ''unconquered'' -- has always been proud of its ability to resist outside influences. ''The only thing that's different,'' said Buffalo Tiger, 81, former chairman of the tribe, ``is the young kids.'' That could mean an entire generation of an already tiny tribe in which every person is a precious resource. Tribal officials estimate there are 500 members on the reservation and 150 more Miccosukees nearby. The tribe knows the problem has reached a critical stage and is addressing it. But there is not necessarily a consensus on how to move forward. Some Miccosukees teach their children at home and send them to the reservation school, where a phonetic version of the language -- first written down by a white missionary nearly half a century ago -- is taught along with English. Others believe tribal culture requires the language be taught only orally, passed from generation to generation. And still others send their children to public school in Miami-Dade or Collier county, where the challenge gets even more complicated. Most tribal members say the casino the tribe runs at Krome Avenue and Tamiami Trail is not directly to blame for diluting the Miccosukee language, but it has had a direct impact on the number of satellite dishes, Internet-connected computers and shiny four-wheel-drive vehicles now so common among the Miccosukees. It's easier than ever for tribe members to travel to the outside world, whether cruising into Miami on the Trail or connecting through the information superhighway. And as several tribe members point out, technology does not often speak their language. Type the phrase ''Miccosukee language'' into the Google search engine on the Internet, and it returns only 29 items, few of which are actually written in Miccosukee. While there may not be a consensus on how to approach the mission, there is a fairly common sense of urgency. 'WRITE IT DOWN' Farther west on the Trail, in chickee-hut villages off the reservation, several ''independent'' Miccosukees unaffiliated with the tribe say the school's language focus will prove to be in vain. They say most reservation children go home to young parents who often speak English at home and that their language is intended only to be spoken, not written or read. ''In their mind, it's part of school,'' Leroy Osceola, 44, said of some of the reservation children. ``It's not part of who they are.'' He said his children will be among the lucky ones because they come home to a father who demands they speak Miccosukee. ON THE WAY OUT? ''In another 10 years, the younger generation will not be able to speak it,'' he said. ``If you don't use your language daily, you're going to lose it in a matter of time.'' The tribal school is an immaculate and well-supplied facility with a security guard at the entrance. Children learn in English, but they are also taught Miccosukee, sometimes spelling out phrases into long words that many adults say they cannot understand. Some children arrive at school knowing little of their language, but others must have English translated for them. The tribe did not respond last week to a Herald reporter's request to visit a class or interview teachers. On a playground near the school on a recent afternoon, English seemed the language of choice. There was considerable debate at one point over who would be ''it'' for an apparent game of tag. Later, among a group gathered at the top of a slide, there was a chorus: ``Me, too! Me, too!'' But inside the quiet school lobby, across from a sign pointing toward an area devoted to ''Miccosukee Language Arts,'' a young teacher sat with a girl on a bench, speaking only Miccosukee. ''We're trying to give them both,'' said Buffalo Tiger, who presents himself as a realist rooted in Miccosukee culture. ``You must learn English and Miccosukee. It's like a hammer and nail. You need them both.'' Depending on whom you ask, the tribe's gambling and tourism ventures have become either a lifeline or a funnel for watering down the soul -- and many see little conflict in balancing both worlds. Joseph Osceola is a 24-year-old product of Miami-Dade County public schools, but his last name, common among the Miccosukees, links him to Chief Osceola, who helped lead a collective of Indian tribes in the Florida Seminole Wars of the 19th century. Most accounts say the tribes were once part of the Creek Confederacy of Alabama and Georgia. Pressure from the federal government forced the tribes to migrate into Florida in the 19th century. The Miccosukee tribe of today is an outgrowth of dozens of Indians who survived by fleeing into the Everglades about 150 years ago. BETWEEN CULTURES ''If you're talking to the old-timers, you talk to them in Miccosukee,'' he said. But when he needs to straighten out the teenagers playing basketball at the reservation gym, ``Sometimes you talk to them in Indian, and they look at you weird.'' Few outsiders know the Miccosukees as well as Harry Kersey, a Florida Atlantic University professor who has written several books about the tribe and its historical and linguistic cousins, the Seminoles. Kersey said the Seminoles, a larger tribe concentrated on an urban Hollywood reservation and around Lake Okeechobee, have not been able to cling to the language with the same collective determination the more remote Miccosukees have. However, former Seminole Chief Jim Billie has been recognized for his efforts to save his native language. Under his direction, members of the tribe have been working to put together a CD-ROM that records their language. But with changes in tribe leadership, the project is on hold. While language is an important part of Indian identity, Kersey said, it's not necessarily crucial. ''It's sad in some ways,'' Kersey said. ``But it's evolved. Maybe it's sad that we don't live the way our 19th-century ancestors lived, but the culture has evolved. People can be very modern and still be Miccosukee. In effect, you're Indian if you think you are.'' In a region that seems to grow richer each year with the different dialects of fortune-seeking migrants, from New Englanders to Nicaraguans, the decline of the Miccosukee language might seem oddly against the grain. Instead, Kersey said, it mirrors the plight of many Spanish-speaking immigrants who, on first arriving in America, work to learn English. A generation or two later, he noted, they often find themselves struggling to pass Spanish on to their grandchildren. 'ANGLO WORLD' Yet with the steady flow of Latin American immigrants into South Florida, the number of people in the region with Indian connections, even tenuous ones, is actually rising. The verbal staccato of the Miccosukee mothers browsing for treats for their children at a Tamiami Trail convenience store struck Edna Apunte as surprisingly familiar when she first became clerk at the little shop on the reservation. That was four years ago, not long after Apunte arrived in Florida from Ecuador. ''In my country, the Indians speak Quechua,'' Apunte said, clicking her tongue to mimic the percussive stops and starts of both dialects. ``The sound is the same.'' |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

The

casino and resort are built. The cash is flowing. The tribe is thriving.

The

casino and resort are built. The cash is flowing. The tribe is thriving.