|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

March 9, 2002 - Issue 56 |

||

|

|

||

|

Tribe Works to Keep Ancient Tradition Alive |

||

|

by Andrea Alexander Special

to the Baton Rouge Advocate

|

||

|

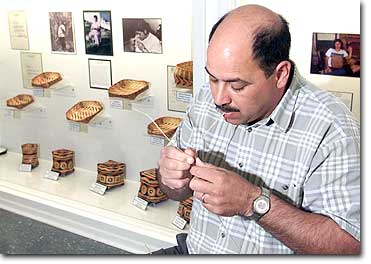

credits: Advocate

staff photo by Bryan Tuck

John Darden, museum interpreter and assistant curator at the Chitimacha Museum, peels away the husk of a piece of river cane in front of a display of traditional Indian baskets woven by some of his relatives. |

CHARENTON,

LA - Imagine having a 6,000-year-old family tradition passed down to you.

John Darden, assistant curator of the Chitimacha Museum, tribal member

and basket weaver, is pretty close to knowing what that means. CHARENTON,

LA - Imagine having a 6,000-year-old family tradition passed down to you.

John Darden, assistant curator of the Chitimacha Museum, tribal member

and basket weaver, is pretty close to knowing what that means.

Darden is not sure if the Chitimacha basket-weaving tradition is as old as archaeologists say the tribe's presence in the area is, but he knows the tradition is so ancient that tribal myths have grown up around it. Those myths, like the basket-weaving process, are kept secret by the tribe. It's a fact, however, that "old-style" woven cane mats were used for burials and cremations during the era of the Mississippi mound-building cultures, Darden said. That historical link proves basket-weaving is a Chitimacha tradition dating to at least the Middle Ages. Darden, his wife, Scarlette, sister Melissa Darden and friend Raymond Thomas are the only remaining local weavers. "We all learned after we were grown," John Darden said. "My sister and I started learning together from our grandmother. I had to actually be working and asking her questions as I constructed a basket in order to learn secrets of the trade. It was hands-on learning. It's impossible to show you instantly how to make a basket." Of late, the Chitimachas' secret craft is being threatened by a shortage of river cane, the material used to make the baskets. On March 6, Darden and other tribal members, as well as school children from the reservation, will plant about 100 river cane plants on tribal land "to have future cane available," said Kim Walden, cultural director for the tribe. The project is a joint effort of the Chitimacha tribe, the National Resource Conservation Service and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, she said. The scarcity of this wild plant that resembles bamboo is the result of heavy pesticide use and environmental changes, Walden said. Plus, river cane does not grow on the reservation. "My grandmother could hardly find any more cane during her lifetime," John Darden said. "But we still learned from our grandparents how to prepare the cane to make baskets. We had to learn it, because no one else was going to do it and because it couldn't be bought. Our grandparents always told us that if we couldn't prepare the cane ourselves, we couldn't make baskets." The process of cutting, splitting, peeling, drying and dyeing the cane is arduous, requiring at least a week, John Darden said. But now, growing the cane promises to be even more tedious. He said usable river cane must first produce a root system and, after that, mature into a stalk that can be harvested. "We don't know how slowly it may spread, because all of the cane we've used until now has come from established plants."

"With the larger baskets, you have to peel through the joints of the cane. The hardest part is stripping and peeling the cane," he said. The tools used? No more than hands, teeth and a knife. The cane is later dyed with the Chitimacha traditional colors: red, yellow and black. Today, John Darden can count 49 different designs used to weave the cane. There's nothing simple about the weaving part of the process, either. "When my sister and I first started learning from Maw-Maw, we had only two baskets to copy designs from," he said. "So we relied a lot on pictures of old baskets, too." Today, baskets with intricate designs can get pricey, running into the thousands of dollars. John Darden once sold a basket for $15,000. Because of the Indians' appreciation of the literal, especially of different creatures, the Chitimacha designs sport names like Alligator Entrails, Muscadine Rind, Bull's Eye, Snake, Perch and Rabbit Teeth. The four-cornered diamond-shaped Muscadine design was named, according to John Darden's grandmother, because "when you smash the berries, it splatters in four different directions," he said. Baskets are made with both single-weave and double-weave designs. Double-weave designs are woven inside and out with a diagonal stitch. John Darden said Chitimacha baskets are strong. Unlike the pine-needle baskets made by other regional tribes, the Chitimacha cane baskets are particularly long-lasting. A specimen in the museum dates back around 150 years. It's because of the basket-weaving tradition that the tribe's local presence has been so long lasting as well. John Darden tells the true story of how Sarah Avery McIlhenny prevented the tribe from losing its land in 1914 to a tax-liability judgment by the federal government. McIlhenny paid $1,200 to the government on behalf of the tribe, receiving a present of baskets in return from tribal weaver Clara Darden, a distant relation of John Darden. "The basket tradition is the reason we still have our land," John Darden said. Today the Chitimacha tribe is in the process of adding almost 700 acres to its 261-acre reservation. The Chitimacha Museum is open 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday. There is no admission fee. The museum can be reached at 337-923-4830.

|

||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

Time

becomes an even more precious commodity when the actual weaving begins.

Sometimes, weaving a larger basket can take more than a year. And it

seems that more clients and collectors are wanting larger baskets these

days, John Darden added.

Time

becomes an even more precious commodity when the actual weaving begins.

Sometimes, weaving a larger basket can take more than a year. And it

seems that more clients and collectors are wanting larger baskets these

days, John Darden added.