|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

February 23, 2002 - Issue 55 |

||

|

|

||

|

Three Indian Teens Face Challenge of Saving Heritage |

||

|

by Laurann Brown, 17 Mackenzie

Flynn, 18 and Stephen Bush, 15 - Y-Press

- February 10, 2002

|

||

|

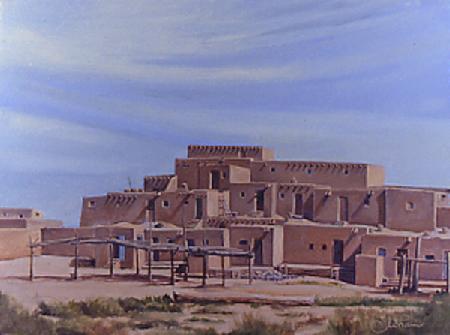

Pueblo ©

1997 Arlington County Cultural Affairs Division

|

Atlanta

Braves. Jeep Cherokee. Indianapolis Indians. Tippecanoe County. Florida

Seminoles. Atlanta

Braves. Jeep Cherokee. Indianapolis Indians. Tippecanoe County. Florida

Seminoles.

When you hear these names in everyday speech, do you think about the connection they have to American Indian culture? Though references to their heritage are widespread, American Indians must work to preserve their history. Recently Y-Press talked with George Kanesta, 15, and Angel Boone, 17, from the Zuni reservation in New Mexico, and Peggy Balog, 18, a Cherokee from Amelia, Ohio. All spoke about the challenge of preserving their heritage. Members of one of 19 Pueblo tribes, Zuni people never lived in teepees, unlike the numerous plains Indians. Their dwellings were mud-brick, apartment-like structures called pueblos. They were not nomadic; instead of following herds of animals for food, they farmed the land. The Zunis' handiwork is pottery, basket weaving and jewelry making. Their language has no apparent roots in any other known language. Two thousand years ago, their ancestors, the Anasazi, lived on the site of the Zuni reservation. Like the Zuni, Cherokees were an agricultural people who lived in large villages. Their houses were made of wattle and daub, a structure of interwoven branches, like an upside-down basket. Today, the largest Cherokee reservations are in North Carolina and Oklahoma, but others can be found throughout the United States. Though similar to Iroquois, the Cherokee language differs greatly in pronunciation. Discrimination and mistreatment of American Indians have been long-standing injustices in the United States. Even finding a term that adequately portrays the indigenous people can cause conflict. Depending on context, the term "Indian" has been considered derogatory by many people, both native and non-indigenous. While George and Angel do not think the word is derogatory, Peggy believes it can be. "It depends on how the term is used. . . . If it's someone that's just trying to carry on a conversation, (it is acceptable)." Peggy, though, prefers the term "Native American." She is offended by some names of sports teams and their mascots, such as the Cleveland Indians. "When people look at a character, they say, 'Oh, that's what people are like. That's what they look like.' It all big fun and games," she said. But that is not the biggest of Peggy's challenges. As a minority in her community of 1,837 just southeast of Cincinnati, Peggy has faced discrimination on a daily basis. She recalled a recent incident with a former high school student: "He put his hand up in my face, and he said, 'How.' I looked him square in the eyes and I asked him, 'How what?' and he didn't really know how to respond to that. He's like, 'Isn't that how you say hi?' And I said, 'No, it's not how you say hi,' " Peggy said. "I tried to educate him, but he did not want to listen. He did not want to stand there and take the time to understand how he was wrong." Angel and George haven't had the same problem on the reservation. "I think discrimination is not really a big problem against Zunis, but I do think it is a big problem against African-Americans and other tribes," said Angel. Most American Indians have a strong sense of pride in their heritage and struggle to keep it alive. It's more difficult for people who, like Peggy, don't live among many Native Americans. "On the reservation, I think there's a lot of people out there that are of Cherokee descent and full-blooded that have preserved it very well," she said. "I think it could be preserved a little bit better than what it is, but it's about as well as can be expected after what a lot of the ancestors have gone through." George and Angel have grown up on the reservation, about 35 miles south of Gallup, NM. Their reservation occupies an area about the size of Rhode Island. While critics argue that living on the reservation can be detrimental because of high crime and suicide rates, others suggest it has been an effective way to preserve their way of life. As of 1997, there were 554 reservations and federally identified Indian lands in the United States. Angel and George said the reservation's crime rate is not so high compared to other towns. George credits the reduction to the small-town atmosphere of the reservation, where everyone knows each other. He pointed out that the reservation government is similar to New Mexico's. "We have a governor, a lieutenant governor and councilmen and women," he said. School is from 8 a.m. until 3:30 p.m. For many American Indians, an important aspect of preserving their culture is coming together with people who share their heritage. This is especially important for families like Peggy's. One way they do this is by attending powwows. At these gatherings, participants perform traditional dances and songs. At most powwows, non-Indians are welcome to observe and learn. Powwows sometimes last several days and often include craft displays, rodeos and cultural exhibits. "We usually go to every powwow that we can, which is about two or three a month, depending on where they're at. And we go to Sundance and stuff in Minnesota," said Peggy, referring to a large multi-tribe religious gathering. "I think it's a very good healing experience when I go to powwows and Sundance and things, 'cause it just mends the soul back together, along with the spirit." Though Peggy has never lived on a reservation, she feels a part of her culture. "Wherever you go, no matter where you're at, you always have that spirit with you," she said. While George and Angel enjoy living on a reservation, they realize its limitations. "I think 90 percent of the time, life on the reservation is good, but other times you feel like there are more opportunities in other places," said George. "I basically want to go somewhere to get a better education and explore what places I haven't seen," he said. But he and Angel want to return to their community and help their people. Another benefit of leaving the reservation is sharing the realities of their lifestyle and culture with others. Peggy and Angel believe that in order to prevent discrimination, people must be educated about cultural differences. "We live in regular houses. We don't live in teepees. We don't ride horses or anything. We wear regular clothes. We drive cars and buy food from the store -- we don't make it ourselves," Angel said. "(I would) just ask them to come down and spend time with us in our village or our pueblos, to see how we live," he said. Y-Press

is a nonprofit news organization located in The Children's Museum of

Indianapolis. Stories are researched, reported and written by teams

of young people ages 10 to 18. For more information, call 1-317-334-4125

or send e-mail. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||