|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

January 26, 2002 - Issue 54 |

||

|

|

||

|

Finding the Words |

||

|

by Michelle Nijhuis-High

Country News-January 21, 2002

|

||

|

|

|

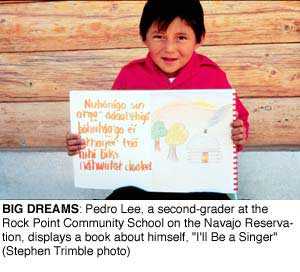

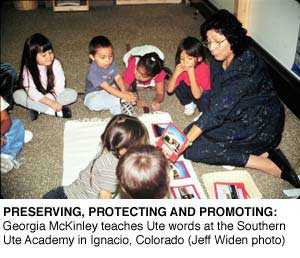

Come in. Come in. Let's talk Ute. Five times a day, five days a week, McKinley uses this greeting to welcome a group of Southern Ute Academy students into her classroom. The kids spend between half an hour and 45 minutes answering her questions about the weather, responding to their Ute names, learning the names for their eyes, hands and feet, and singing songs. "Uu means yes, kach means no," they chant. "Uu, kach. Uu, kach." The academy, now well into its second year, is the nation's only tribally funded Montessori school. Its gleaming, airy building, near the grounds of the old government boarding school was underwritten almost entirely by tribal oil and gas revenues. Inside, 90 students ranging from infants to nine-year-olds are bathed in attention by McKinley and a cadre of teachers. McKinley, who is in her late 50s, is one of about 100 fluent Ute speakers on the Southern Ute Reservation in Colorado. She has a group of friends her age who also speak Ute ("Ah, when we get together, we always end up laughing," she says), but sometimes she has to keep in practice by speaking Ute to her cats. She can blame her lack of company on the boarding-school classes of her childhood, where teachers spoke only English and punished students for speaking Ute. Many of McKinley's classmates, hoping to save their own children from similar ridicule, spoke only English at home in later years. So the parents of today's Montessori students know only a smattering of Ute words, and the students themselves may not have heard the language until they entered this classroom. McKinley's quiet Ute greetings belie a ferocious sense of urgency on Western reservations. Once you lose your language, it's often said, you lose your culture. You lose your private jokes, your custom-designed, place-precise vocabulary. You lose one of the few remaining things that binds your tribe and distinguishes it from the rest of the world. And once these unique words are gone, they're really gone. Despite the superhuman efforts of linguists and frail tribal elders, there's no way to fully preserve a language on paper. "There are two intersecting lines," says Darrell Kipp, the director of the Piegan language institute on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana. "One is the number of years our fluent speakers have left, and the other is the amount of time it takes to produce new speakers. When those lines no longer intersect, we'll have lost our language - forever."

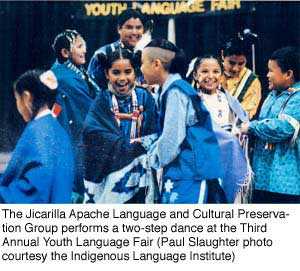

A fatal spiral Eastern languages were the first to go, followed by many languages from the Great Plains and California. Tribes in the Northwest and Southwest, which hung on to their isolation the longest, also hung on to their vocabularies longer than most. Today, the Southwestern tribes and their larger land bases are some of the best refuges for indigenous languages. Mission schools and government schools, especially government boarding schools, hurried the decline along. After the end of the Civil War, cultural cohesion was high on the national agenda, and language differences were blamed for the continuing strife on the Western frontier. "In the difference of language to-day lies two-thirds of our trouble," a group of peace commissioners appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant wrote in 1868. "Schools should be established, which (Indian) children should be required to attend; their barbarous dialect should be blotted out and the English language substituted." Such rhetoric infected the Bureau of Indian Affairs. From the late 1800s into the 1970s, the agency pursued a nearly uninterrupted policy of severe assimilation for young tribal members. The agency forced thousands of students to attend government boarding schools far from reservations, and did its best to rub out tribal traditions and replace them with Anglo ways. Boarding-school officials lopped off boys' long hair and stripped all students of their cultural identity. "They gave us government lace-up shoes, and they gave us maybe a couple pair of black stockings, and long underwear ... (and) slips and dress," Lilly Quoetone Nahwoosky, a Comanche tribal member, recalled in 1981. "Then they gave us a number. My number was always 23." Students who spoke their tribal languages were beaten or had their mouths washed out with soap. When they returned home after years away from the reservation, many had only a vague memory of their language and culture, and were ashamed to admit to the little knowledge they had. The assimilationist arguments they heard so often in boarding school filtered back to their families, their children, and their fellow tribal members. The result was a death spiral for tribal languages, one still circling over most reservations. While many languages still have active speakers, most of the languages themselves are zombies, missing the new generation of speakers needed to keep them going. "Even in healthy language communities, we're seeing that younger children are drifting away," says Inee Yang Slaughter of the Indigenous Language Institute in Santa Fe, N.M. "That's scary, because a language, when not used, is not vibrant." In many cases, there aren't enough speakers to add new words, so telephones, helicopters, computers and other gadgets must be described with unwieldy compound words. And because most new speakers learn their language in a classroom instead of in the home, slang is fading from conversation. Dick Littlebear, the president of Chief Dull Knife College on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in Montana, says his language is losing what he calls the "spice" words, the colorful, untranslatable words that are all but impossible to teach. "Most of these words, I use them all the time when I'm talking Cheyenne," he says, "but when I try to dredge them up in English, I can't do it." The loss of these unique words is especially serious, because most tribal languages are entirely oral. Though grammars and dictionaries have been developed by tribal elders and linguists (and, in some cases, by frontier-era priests) there are even fewer writers than speakers. It's very difficult to protect vocabulary that's infrequently used; Littlebear says entire topics have already disappeared from the Cheyenne language. "I remember my grandfather saying, 'This is what you call a horse, this is what you call a cart, this is what you call feed,' " he says. "Of course, when you're young, you don't pay attention. Now I wish I had." Some tribes have been able to resist this fatal spiral, either through persistence or the force of numbers. The Crow tribe in southeastern Montana, which has a reputation for insularity, has about 9,800 enrolled members and, according to the 1990 Census, about 4,200 native speakers - including as many as 20 monolingual Crow speakers. The language is so common on the reservation that the tribe holds its business meetings in Crow. Dine or Navajo, the language of the nation's largest tribe, counts nearly 150,000 speakers out of about 220,000 members. But a list of the West's native languages tells the rest of the story. The numbers of speakers drop quickly into the hundreds, the tens, the single digits. The list ends with a string of ones, the most human-looking numbers you can imagine: Each of these stands for the single remaining speaker of Mandan in North Dakota, Eyak in Alaska or any one of a steadily lengthening roster. These people, in their 80s or 90s or beyond, must get up each morning in a heavy fog of loneliness. They have, literally, no one left to talk to. "The house is afire" During the Great Depression, reform-minded Bureau of Indian Affairs Commissioner John Collier tried to make these whispers louder, relaxing the official policy toward tribal languages. But the conservative reaction to Roosevelt's New Deal choked off these reforms, says Jon Reyhner, a professor at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff and the author of several books on Indian education. In the 1950s, says Reyhner, the federal government returned to its harsh language policies, and even began to "terminate" tribes by stripping them of their official recognition. Only a few people off the reservation recognized that tribal languages were hemorrhaging words. One was the eccentric California linguist J.P. Harrington. From the early 1900s until his retirement in 1954, Leanne Hinton writes in her book Flutes of Fire, Harrington studied more than 90 tribal languages throughout the Americas, taking more than a million pages of notes in his nearly illegible handwriting. Today, his notes and recordings are the only clues to several extinct languages. "The time will come and soon when there won't be an Indian language left in California," he wrote to a young assistant in 1941. "All the languages developed for thousands of years will be ashes, the house is afire, it is burning." During World War II, 29 Navajo soldiers known as the Code Talkers helped sound the alarm. They developed a code based on their unique native language, introducing it to a top-secret group of soldiers from the Navajo, Hopi, Comanche and other tribes. Despite the best efforts of enemy cryptographers, the code was never broken. The Code Talkers provided more than one valuable service, says Joyce Silverthorne, the education coordinator for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of northwestern Montana. After their work was declassified in 1968, she says, "There was finally a recognition that the loss of heritage and loss of language were of sincere concern to this country." Thanks in part to the Code Talkers and the civil rights movement, the Bureau of Indian Affairs policy against tribal languages in schools began to soften in the late 1960s. The Bilingual Education Act of 1968 provided some money for bilingual instruction at federally funded tribal schools; the Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975 granted tribes control of the majority of these schools. Tribal languages received their biggest official boost in 1990. The Native Languages Act vowed to "preserve, protect and promote" the right of tribal members to speak and teach tribal languages, and a later amendment provided some funding for language-education programs through the federal Administration for Native Americans. These policy changes mirrored an expanding language-rescue operation on reservations. "There's an enormous amount of energy around this issue," says Ruth Yellow Hawk of the Indigenous Issues Forums in Rapid City, S.D. At the National Indian Education Association annual conference in Montana this fall, she says, "Every other workshop was about language. People were saying, 'We're racing against time. We have to find willing elders to teach us.' " It's not easy to resuscitate a language. Textbooks are all but nonexistent, and there are no study-abroad programs. Tribal members raised to disparage their language often refuse to support or outright oppose education efforts. Perhaps the most serious problem is that elders, the last reserves of tribal language, often have a hard time passing on their knowledge. "We're asking an enormous amount of our elders," says Joyce Silverthorne. Since many elders were separated from their families at a young age, their knowledge of the tribal language isn't perfect, and they often have terrible memories of their own time in classrooms. "Now, we're asking them to go into a classroom and explain the language to an English-speaking child," she says. It's especially difficult for some elders to hear new speakers try out the tribal language, she says: "When elders hear learners in a 'baby talk' phase, with inappropriate pronunciation and grammar, they fear the language is always going to be used inappropriately." Despite these troubles, elders have been enormously active in language revitalization projects. In Montana, the state can certify tribal elders as language specialists, allowing them to teach in public schools without a four-year degree. The Oregon Legislature approved a similar law in June, and elders of the Confederated Tribes of Umatilla in eastern Oregon are working with linguists to preserve some disappearing dialects. In Lewiston, Idaho, Nez Perce elder Horace Axtell is one of several teachers of the Nez Perce language at Lewis-Clark State College. Elders of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai and the Northern Cheyenne tribes teach at summer language camps. Many of these programs are exposing a new generation to these vulnerable languages, but they're not creating the real life preserver: young, fluent speakers. Georgia McKinley, the Southern Ute language instructor, says her brief classes alone won't protect her language from extinction. She gets quiet and hesitant when she talks about the future. "I just ... I just hope that they somehow use it as they grow older," she says. "As far as them speaking it fluently ... I hate to say it, but that's not going to become a reality."

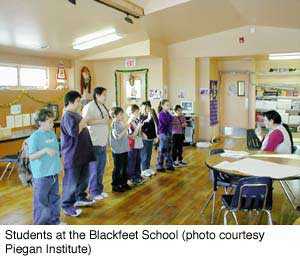

Education without

permission Kipp grew up speaking Blackfeet at home with his parents and grandparents. After graduating from high school, he left the reservation in the 1960s to attend the state university in Bozeman, serve a tour of duty in Vietnam, and earn master's degrees from Goddard College and Harvard University. By the early 1980s, he says, "I was homesick." He and a small group of Blackfeet friends decided it was time to return to the reservation. They hoped to relearn their language, and some wanted to raise Blackfeet-speaking children. They were shocked to find that, while they'd been away, the number of fluent speakers had dropped dramatically, and all of the remaining speakers were more than 60 years old. But few of their peers shared the group's concern. "We met people who could not only not speak the language, but also had a negative view of the language," he says. "It was a very hostile environment." Kipp and his friends persisted, founding the Piegan Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to restoring, protecting and preserving Native American languages, in 1987. They discovered that the only programs producing new speakers were privately funded language-immersion schools, where students spoke the language all day, every day. The Blackfeet activists found that the Akwesasne Freedom School, in upstate New York, founded by Mohawk parents in 1979, had been immersing Mohawk children in the tribal language since 1985. The Maori of New Zealand had founded a system of early childhood immersion centers, known as Kohanga Reo or "language nests," in 1982. Native Hawaiians had also established a similar immersion-school system in 1983, and have since extended the program through the 12th grade. "What we're trying to do is take our traditional language and culture and put it back into today's modern world," says William Wilson, one of the founders of the privately funded ÔAha Punana Leo schools and the father of two of their first high school graduates. "That's a difficult thing. Most people don't understand how strong English is in this country." About 50 Hawaiian-speaking students have graduated from the immersion high schools since they opened in 1999. The Piegan Institute was impressed by these successes, but the group faced a major problem. Though there were still several hundred speakers of the Blackfeet language, there were no trained teachers. With the help of two elders, the institute immersed six young teachers in the Blackfeet language. To almost everyone's surprise, the experiment worked. "One of the fallacies is that people cannot learn a second language as adults," says Kipp. "In the typical beginning language class in a college or high school, only five out of every 100 students ever master the language. So you've got 95 other people walking around saying, 'Well, I took French, but I'd starve to death in a French restaurant.' " With Blackfeet-speaking teachers on hand, the Piegan Institute opened the Nizi Puh Wah Sin, or Real Speak School, in 1994. "One of our rules was, 'Do not ask permission to save your language,' " says Kipp. "If you go to the school board and say, 'Can we teach the language for a few hours? Can we have a building?' you're asking permission." The institute applied the same rule to the tribal council, refusing to ask it for permission - or for money - so the school's $170,000 annual budget depends entirely on foundation funding, private donors, and what Kipp calls a "symbolic" tuition of $100 per month. To overcome resistance on the reservation, the Piegan Institute interviewed tribal elders about their experiences with the language. The institute wrote and directed a video of these interviews, made 2,000 copies and distributed them around the reservation. The video helped. "People realized that we did not quit using the language out of choice," says Kipp. "Our parents and grandparents were forced to. They didn't pass the language down, because they loved us, and didn't want us to suffer the same abuse." Today, the Real Speak School has 36 students, from kindergartners to eighth-graders, and many more applicants for its kindergarten class than it can accept. Its first graduate, who is fluent in English and Blackfeet, now attends a public high school on the reservation. Yet the teachers and the students at the Real Speak School are the only new Blackfeet speakers. When Kipp first returned to the reservation, there were about 1,000 fluent speakers. Today, there are fewer than 500. "It took 500 years, and enormous expense, to almost get rid of these languages," says Kipp. "They aren't going to recover in one year, or two years, or with a $50,000 grant or a bilingual program. What we need is a full-fledged, multi-year process to reinvigorate the language."

"Real

validation" "It's a very deep rejuvenation of the community," he says. "When our children go into the community and speak the language, or when they remind people that it's time to say a prayer, people are overwhelmed. They say, 'That's too much! I want one of those kids!' " Children who are comfortable with their own language and culture, he says, are comfortable with themselves. That means fewer dropouts, fewer attendance and discipline problems, and many more successful students. In Indian Country, where the youth suicide rate is nearly three times the national average, such programs can be literal lifesavers. It's a complete turnabout of the boarding school era philosophy, which maintained that tribal languages would only isolate tribes from the dominant culture. This argument still echoes on the reservation, but it is losing strength. "Now, there's a recognition that people are better off being multilingual," says Mark Trahant, a journalist and member of the Shoshone-Bannock tribe. "These languages contain a way of looking at the world that has a 10,000-year history ... Those of us who don't speak our language are viewed as less prepared for the world." About 30 tribes have visited the Blackfeet school, and the Washoe have already started a similar program in the Lake Tahoe area. Laurie Betlach of the Santa Fe, N.M.-based Lannan Foundation estimates that 50 tribes in the United States are considering language-immersion programs of their own. In California, where many languages are balancing on the very edge of extinction, tribes are pairing fluent speakers with younger students in a sort of mini-immersion program called a master apprenticeship. Though attitudes are changing, tribal-language education still faces hostility off the reservation, and public school programs are particularly vulnerable. Joyce Silverthorne, who oversees the Salish and Kootenai language-instruction programs in seven public high schools in Montana, was horrified when the Montana Legislature passed a bill in 1995 making English the "official and primary" language of the state. Though the law hasn't directly affected her programs, she fears it opens the door to future restrictions. Silverthorne is now looking nervously south to Colorado, where anti-bilingual education activist and California software entrepreneur Ron Unz has succeeded in getting his "English for the Children" initiative on the 2002 ballot. Unz has already backed similar winning measures in California and Arizona, and Silverthorne fears her state isn't far down the list. Unz says his measure, which prohibits mandatory bilingual programs in public schools, isn't aimed at either public or private tribal language programs. Silverthorne isn't reassured. "We've always recognized the advantage that the rich child has in learning another language," she says. "We've never valued the richness that other children bring with them, the native knowledge of another language. That's a hypocritical stance that needs to be addressed." Language activists point to other, more hopeful signs. Ofelia Zepeda, a Tohono O'odham poet and linguistics professor at the University of Arizona, was awarded a MacArthur "genius grant" in 1999 for her work with native languages. In July 2001, the 29 original World War II Code Talkers were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation's highest military distinction. The year before, Hasbro Toys had released a Navajo Code Talker G.I. Joe doll, complete with seven recorded Navajo phrases. "When we see a Navajo G.I. Joe, that's something that's common to all children," Silverthorne says with a laugh. "That's real validation." Language-rescue operations have become a lot more sophisticated since the days when little girls whispered to each other in boarding school dormitories. But individual acts still help keep these languages alive. Silverthorne, who is working on her doctorate in educational leadership, is writing her dissertation on adult students of tribal languages. After surveying tribes in the Northwest, she found 21 people who had become fluent in their tribal language as adults. Most of these were solo learners, motivated not by an immersion school or public school program but by a desire to learn their own language before it was too late. "There's a passionate recognition that language is being lost," says Silverthorne. "Young people acknowledge and understand that loss of language is going to change the people we are." Southern Ute teacher Georgia McKinley might not be creating fluent speakers yet, but she hasn't given up on her language. When her young students started using Ute words at home, so many parents requested lessons that McKinley started an evening language class for adults. After a long day of teaching at the academy, she's rushing off to meet with another teacher, a young woman who's learned enough Ute to help her with the adult class. McKinley also has at least one special project: She wants academy principal Carol Oguin to talk Ute, too. Oguin stopped speaking the language when she entered public school at age five. "I can understand Georgia, and she is bound and determined to make me a Ute speaker again," says Oguin with a big laugh. "She talks to me in Ute all the time, and I'm getting to the point where I can answer her more and more. So she might get her wish." Until Dec. 31, 2001, Michelle Nijhuis was

HCN's senior editor. Carol Oguin, Southern Ute Academy, 970/563-0100,

ext. 2711; |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

IGNACIO,

Colo. - "Yuga', yuga'," says Georgia McKinley, as a line of

four-year-olds snakes through the door of her classroom. "Nuuwaigeavaro,"

she adds rhythmically, gently shaking each child's hand.

IGNACIO,

Colo. - "Yuga', yuga'," says Georgia McKinley, as a line of

four-year-olds snakes through the door of her classroom. "Nuuwaigeavaro,"

she adds rhythmically, gently shaking each child's hand. Keeping

track of languages is a slippery business, as they constantly morph,

merge and split apart. But linguists estimate there were 300 languages

in North America before European settlement. That number shrank faster

than you can say Manifest Destiny, and at the beginning of the 21st

century, there are just 150 of those languages left. Most of those are

in steep decline.

Keeping

track of languages is a slippery business, as they constantly morph,

merge and split apart. But linguists estimate there were 300 languages

in North America before European settlement. That number shrank faster

than you can say Manifest Destiny, and at the beginning of the 21st

century, there are just 150 of those languages left. Most of those are

in steep decline. Rescue

operations for tribal languages began long ago, when children started

to whisper the familiar but forbidden words in their boarding-school

dorms. Frances Jack, a member of the Hopland Band of Pomo Indians in

California, was strapped for speaking her language at a government school

in California in the 1920s, but she continued to break the rules. "I

just couldn't help it; I talked my language," she told linguist

Leanne Hinton in the early 1990s. "Others did, too, but so that

nobody heard them."

Rescue

operations for tribal languages began long ago, when children started

to whisper the familiar but forbidden words in their boarding-school

dorms. Frances Jack, a member of the Hopland Band of Pomo Indians in

California, was strapped for speaking her language at a government school

in California in the 1920s, but she continued to break the rules. "I

just couldn't help it; I talked my language," she told linguist

Leanne Hinton in the early 1990s. "Others did, too, but so that

nobody heard them." On

the Blackfeet reservation in northwestern Montana, next door to Glacier

National Park, Darrell Kipp is determined to make young, fluent Blackfeet

speakers a reality. He's been working at it for 15 years.

On

the Blackfeet reservation in northwestern Montana, next door to Glacier

National Park, Darrell Kipp is determined to make young, fluent Blackfeet

speakers a reality. He's been working at it for 15 years. The

Blackfeet program and its counterparts are reinvigorating a very particular

kind of biodiversity: the rainforest of rare words, complex sentence

structures, obscure roots and hidden meanings contained in each of the

world's languages. Kipp says the program is also on a much larger mission,

one of social and cultural restoration.

The

Blackfeet program and its counterparts are reinvigorating a very particular

kind of biodiversity: the rainforest of rare words, complex sentence

structures, obscure roots and hidden meanings contained in each of the

world's languages. Kipp says the program is also on a much larger mission,

one of social and cultural restoration.