|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

December 15, 2001 - Issue 51 |

||

|

|

||

|

Brainstorming |

||

|

by Michael Jamison

of the Missoulian-December 9, 2001

|

||

|

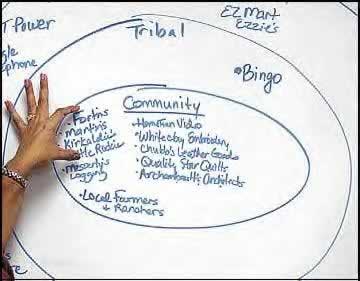

Photo

by Kurt Wilson of the Missoulian

|

|

Indian women often bring a different style of leadership to the reservations, one that focuses on community building rather than elections and titles. On Montana's reservations, Indian women are leading the effort to create social change among their people through education.

It is nothing new to say that America's Indian reservations are awash in poverty, propped up by welfare, and that along with generations of welfare have come generations of other social ills: drugs and alcohol, physical and emotional abuse, divorce, despair and the demise of the family. But systemic poverty cannot stand long in the face of education, or such is the hope, and Indians - particularly Indian women - are leading an intellectual renaissance from tribal colleges to economic independence. "I see a big breakthrough here," said Margaret Campbell. "Indian people are valuing education like never before." Campbell spent 14 years as president of the tribal college on Montana's Fort Belknap Reservation, and now is vice president at the Fort Peck tribal college. The Assiniboine woman also is president of the national American Indian Higher Education Consortium, where she lobbies on behalf of tribal colleges. "Education is the answer to a lot of our problems," Campbell said. "It opens minds and it opens opportunities. Before we're able to make any kind of serious social change, we'll need an educated community." In today's Indian Country, much of the serious social change is coming from women, and many of those women are emerging as community leaders only after first having nailed down an educational foundation. In fact, the single common thread that runs through Indian Country's new breed of women leaders is education. Education, Campbell said, has allowed the women to take over the sophisticated tribal programs that demand some schooling know-how, and so provides the springboard for women to step up from leaders at the program level to leaders at the elected level. "It's simple," said Caroline Brown, a Gros Ventre woman who directs an economic development office on the Fort Belknap Reservation. "Women get the education in Indian Country, and so women get the important jobs." According to the Albuquerque-based Center for Native Peoples, 76 percent of Indians pursuing a higher degree are women. And statistics from Montana's tribal colleges show about 72 percent of students are female, half of whom are single mothers and 85 percent of whom live below the federal poverty line. In addition to making up the bulk of tribal college students, women also are running the tribal colleges, teaching at the tribal colleges, working in research arms of the tribal colleges. "It was women, for the most part, who were behind the very creation of the tribal colleges," said Carol Juneau, a lifelong educator and a state representative from the Blackfeet Reservation. To say that many more Indian women than men are pursuing a higher education, however, is not to say that very many Indian women are in college. According to Juneau, about 50 percent of Indian students drop out of high school. Of the half that make it, perhaps 5 percent go on to receive a four-year college degree, the lowest rate of any minority in the country. That compares to about 25 percent of white adults who receive a university education. An ongoing research project aimed at determining why some Indian students succeed while others drop out has as its focus four tribal colleges here in Montana. Called the "Family Education Model," the 4-year-old project is a collaborative effort between the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the University of Montana and tribal colleges on the Blackfeet, Fort Peck, Flathead and Rocky Boy's reservations. Obstacles to staying in school, according to the study, include rural isolation, the demands of single parenting, housing shortages, lack of day care and transportation, severe poverty and a lack of jobs that keeps reservation unemployment hovering between 50 and 85 percent. But Campbell believes many of those obstacles to education can be eliminated, ironically, through education. More than 90 percent of tribal college graduates in the study, for instance, found work straight out of school. And because so many more Indian women than men are pursuing education, that means women are claiming the best reservation jobs. "More or less, you can't come up from the school of hard knocks anymore," said Janine Pease-Pretty On Top, former president of the Crow tribal college and owner of a consulting firm that secures millions of dollars for education in Indian Country. "It used to be you could learn what you needed to know on the way up through the ranks. Those days are gone. You must have an education if you are to keep up." Women had a head start on education, Pease-Pretty On Top said, because fledgling tribal colleges often start with "women's classes." "In part, it reflects the fields of study the colleges have chosen to offer in their early years," she said. "They offer health, education, social services, child welfare. Those are programs that are very easy, from a cultural point of view, for women to enter into." The "men's classes," such as heavy equipment operation, construction, natural resource management, are very expensive to set up, she said, which means they come into the curriculum later, if at all. "Colleges choose affordable programs based on community needs," she said, "and that has resulted in programs aimed at women." And the more women who attend college, the more women who attend college. "It runs in families," said Majel Russell, an attorney and member of the Crow tribe. "If your mother went to college, you're more likely to go to college." Like nearly all the women leaders in today's Indian Country, Russell comes from a long line of college-educated Indians. Her grandma's brothers went to a Baptist college back in the 1920s. Grandma herself earned a teaching certificate. Then came more teachers, a school principal, an attorney, another attorney, a brother with a Ph.D. in geophysics. "I have a fairly unusual family," Russell said. "Our family had a real expectation that everybody would go to college." It has been a boon for her and her siblings, she said, but, in Indian Country, it also can be a burden. "There's still a real cultural issue with trusting people who are educated," she said of reservation life. "It's always an uphill battle to be accepted as just a tribal member and a member of the community." She bridges the gap by speaking fluent Crow and serving as tribal attorney, while at the same time keeping a private practice just off the reservation boundary. Other educated women have found more acceptance, and have reconciled a modern education with traditional beliefs. Take, for instance, Naida Lefthand, a traditional Kootenai woman from the Flathead Reservation who waited until her husband had died and her children had grown before returning to school. At an age when most are retiring, Lefthand was earning a two-year degree in business management. Now, she is enrolled in a four-year program in marketing with plans for a master's degree. She is going to school to make the traditional extended family work in the modern world, "to school to help my children with their children," Lefthand said. In her culture, grandmothers always helped raise the kids. Now, her education has allowed her to take a job as financial officer for the tribe's economic development office, where she makes a decent wage. "As a grandmother, I want to help raise my grandchildren," she said. "And these days, a pair of Nikes costs $100." Education, then, can be seen as a new twist on an old tradition rather than an assault on tradition. That fact is understood well by the modern-day grandmother of the Indian woman's leadership movement, Wilma Mankiller, former principal chief of the Oklahoma Cherokee Nation. "I always tell college recruiters," Mankiller said, "if you're going to go out in the more traditional communities and recruit college students, don't go out and tell them that if they get a college education, that the college education will help them accumulate great personal wealth, or great personal acclaim, or help them get a BMW or whatever. Tell them that they can use their skills to help rebuild their community, and help their family, and help their tribe, and you might get their attention." Combining modern education with ancient tradition and culture is the only way to bring college within reach of most Indians, Mankiller said. "Nothing's really changed," said Pease-Pretty On Top. "Women's job is to raise the kids. Well, if you're going to raise your kids as a single mom, you need an income, and the one sure way to get an income is to get an education." Most of that education, she said, begins at the tribal college level, where Indian students keep one foot in both worlds, bridging white and Indian cultures. "Our colleges are the intellectual base of the reservations," said Gail Small, a Cheyenne and director of the nonprofit Native Action group. "Our colleges are where we go for the broad picture, for our strategy and our plans for the future." If that is true, and if it is true that far more Indian women than men are attending those intellectual bases, then it is no wonder that education is the common thread of today's woman leaders in Indian Country. "Women have a very long-term vision of their tribe," Small said, "and any long-term thinking must include a strong emphasis on education. Women don't govern in the short-term. They are in it for the long-haul, for their children's children's children, and so they're working for lasting change. Education is the root of that kind of change, the kind of change that will alter Indian Country forever."

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

BROWNING

- If you think education is expensive, try supporting a welfare state

the size of Indian Country.

BROWNING

- If you think education is expensive, try supporting a welfare state

the size of Indian Country.