|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

November 17, 2001 - Issue 49 |

||

|

|

||

|

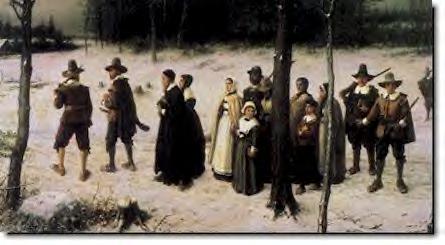

Rethinking Thanksgiving |

||

The Pilgrims

had the "first" thanksgiving feast in the New World in the fall of 1621. Isn't that what you were taught

in school? Guess what? Nothing could be further from the truth! The Pilgrims

had the "first" thanksgiving feast in the New World in the fall of 1621. Isn't that what you were taught

in school? Guess what? Nothing could be further from the truth!For thousands of years, people all over the world have given thanks for good harvests. The ancient Egyptians gave thanks to their gods for the Nile River floods that irrigated their crops. The Chinese give thanks to their gods and honor their ancestors. The Greeks and Romans celebrated with feasts, pageants, and parties. All over Europe, Indian, Africa, North and South America there have been feasts of thanksgiving. The first people of North America were no different. They thanked the Creator for successful hunts and for bountiful harvests. Before the Pilgrims arrived, in 1620, Native Americans, on the eastern shores of North America, had already had contact with English and Spanish explorers. In fact, smallpox was first encountered by the Native Americans in 1617. This epidemic killed nearly half of the Native Americans that came in contact with it. The Wampanoag Indians that had the first contact, with the Pilgrims, were not the "friendly savages" some of us were told about when we were in grade school. The Wampanoag were members of a widespread confederacy of Algonkian-speaking peoples known as the League of the Delaware. For six hundred years they had been defending themselves from the Iroquois, and for the last hundred years they had also had encounters with European fishermen and explorers but especially with European slavers, who had been raiding their coastal villages. They knew something of the power of the white people, and they did not fully trust them. But their religion taught that they were to give charity to the helpless and hospitality to anyone who came to them with empty hands. There were two language groups of Indians in New England at this time. The Iroquois were neighbors to the Algonkian-speaking people. Leaders of the Algonquin and Iroquois people were called "sachems" (SAY chems). Each village had its own sachem and tribal council. Political power flowed upward from the people. Any individual, man or woman, could participate, but among the Algonquins more political power was held by men. Among the Iroquois, however, women held the deciding vote in the final selection of who would represent the group. Both men and women enforced the laws of the village and helped solve problems. The details of their democratic system were so impressive that about 150 years later Benjamin Franklin invited the Iroquois to Albany, New York, to explain their system to a delegation who then developed the "Albany Plan of Union." This document later served as a model for the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution of the United States. These Indians of the Eastern Woodlands called the turtle, the deer and the fish their brothers. They respected the forest and everything in it as equals. Whenever a hunter made a kill, he was careful to leave behind some bones or meat as a spiritual offering, to help other animals survive. Not to do so would be considered greedy. The Wampanoags also treated each other with respect. Any visitor to a Wampanoag home was provided with a share of whatever food the family had, even if the supply was low. This same courtesy was extended to the Pilgrims when they met. Then, there's the Pilgrims. The Puritans were not just simple religious conservatives persecuted by the King and the Church of England for their unorthodox beliefs. They were political revolutionaries who not only intended to overthrow the government of England, but who actually did so in 1649. The Puritan "Pilgrims" who came to New England were not simply refugees who decided to "put their fate in God's hands" in the "empty wilderness" of North America, as a generation of Hollywood movies taught us. In any culture at any time, settlers on a frontier are most often outcasts and fugitives who, in some way or other, do not fit into the mainstream of their society.  One hundred and two Pilgrims left England, on the Mayflower. Of that original group, only fifty

survived the first year. Without the help of the Wampanoag, most of those left would have probably died. One hundred and two Pilgrims left England, on the Mayflower. Of that original group, only fifty

survived the first year. Without the help of the Wampanoag, most of those left would have probably died.So, what really happened? We know that Squanto, who could speak some English, taught the Pilgrims many things. He showed them how to hunt and fish, and how to preserve their catches. He taught them how to cultivate corn and other new vegetables. He pointed out poisonous plants and showed how other plants could be used as medicine. He explained how to dig and cook clams, how to get sap from the maple trees, use fish for fertilizer, and dozens of other skills needed for their survival. The Pilgrims did have a feast, after their first harvest, and it is this feast which people often refer to as "The First Thanksgiving". This feast was never repeated, though, so it can't be called the beginning of a tradition, nor was it termed by the colonists or "Pilgrims" a Thanksgiving Feast. In fact, to these devoutly religious people, a day of thanksgiving was a day of prayer and fasting, and would have been held any time that they felt an extra day of thanks was called for. A letter written by Edward Winslow, in 1622 describes the actual feast. "Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruits of our labors . . . many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain [Myles Standish] and others." This Thanksgiving feast was not repeated the following year. But in 1623, during a severe drought, the pilgrims gathered in a prayer service, praying for rain. When a long, steady rain followed the very next day, Governor Bradford proclaimed another day of Thanksgiving, again inviting their Indian friends. It wasn't until June of 1676 that another day of Thanksgiving was proclaimed. On June 20, 1676, the governing council of Charlestown, Massachusetts, held a meeting to determine how best to express thanks for the good fortune that had seen their community securely established. By an unanimous vote they instructed Edward Rawson, the clerk, to proclaim June 29 as a day of Thanksgiving. October, of 1777, marked the first time that all 13 colonies joined in a Thanksgiving celebration. It also commemorated the patriotic victory over the British at Saratoga. But it was a one-time affair. George Washington proclaimed a National Day of Thanksgiving in 1789, although some were opposed to it. There was discord among the colonies, many feeling the hardships of a few Pilgrims did not warrant a national holiday. And later, President Thomas Jefferson scoffed at the idea of having a day of Thanksgiving. Thanksgiving day continued to be celebrated in the United States on different days in different states until Mrs. Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of Godey's Lady's Book, decided to do something about it. For more than 30 years she wrote letters to the governors and presidents asking them to make Thanksgiving Day a national holiday. Hale's obsession became a reality when, in 1863, President Lincoln, in an effort to heal some of the scars of the Civil War, proclaimed the last Thursday in November as a national day of Thanksgiving. Thanksgiving was proclaimed by every president after Lincoln. In 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt advanced Thanksgiving Day one week. However, since some states used the new date and others the old, it was changed again 2 years later. The reason Franklin D. Roosevelt moved Thanksgiving from the last Thursday of November...was commercialism. He hoped to woo retailers, who complained that they needed more time to "make proper provision for the Christmas Rush." This move of the date outraged a few folks, notable Republicans, who claimed Roosevelt was trampling sacred traditions. For two years, people celebrated Thanksgiving on one of two different days, depending on their political inclinations! And in 1941, Thanksgiving was finally sanctioned by Congress as a legal holiday, as the fourth Thursday in November. And, on a personal note, the events of the past few months have left many of us shaken. No matter if you consider Thanksgiving a day of feasting, or a day of mourning, It is my hope that we use this day to reflect, not only on our individual situations, but on our lives, our families and our friends. |

|

Do you know what foods were here long before the Europeans arrived?

Find out here: |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||