|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

August 25, 2001 - Issue 43 |

||

|

|

||

|

American Indians Stranded in 19th Century |

||

|

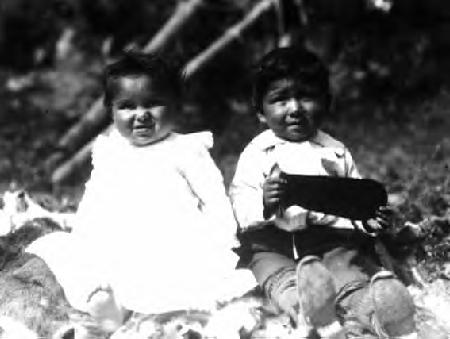

Alfred Kroeber photographed these Yurok children in 1907 |

||

WEITCHPEC,

CA -- The telephone may be coming to the heart of the Yurok reservation, 125 years after it was invented. WEITCHPEC,

CA -- The telephone may be coming to the heart of the Yurok reservation, 125 years after it was invented. Many of the Yurok, who live in a ruggedly beautiful river gorge in far Northern California, are stranded in the 19th century. They're among more than half of American Indians on reservations nationwide who lack phone service. "What that means in real terms is if you have a heart attack, you cannot get to the phone and you die," says Karen Buller, president and chief executive of the Santa Fe, N.M.-based National Indian Telecommunications Institute. The Yurok are working on getting to a phone. When Verizon Communications, formerly GTE, decided to sell telephone assets to Citizens Communications, the Yurok and the neighboring Hoopa Valley Tribe lobbied the California Public Utilities Commission to make more phone connections a condition of the sale, and the PUC agreed. Phones aren't the only technology the Yuroks lack. The waves of prosperity emanating from California's high-tech boom of the '90s didn't cause a ripple among these fir-covered hills, 360 miles north of Silicon Valley. Nearly 70 percent of the reservation lacks not just phones, but power. Some residents have generators and gas-powered refrigerators; others live in bare-board shacks heated by wood stoves and lit by kerosene lamps. "It's the Third World," says tribal member Bertha Peters. "It's hard on the schoolkids -- to do their homework ... all they have is this little light." Most of the 1,500 residents of the 55,000-acre reservation live along its western edge, close to the coastal city of Eureka, and utilities have reached that far. But the power lines stop at the village of Weitchpec, about 60 miles inland, and there's no phone service for about 15 miles on either side of Weitchpec. Cell phones don't work here. The tribe has put up a tower powered by solar panels and hydrogen that provides two lines through microwave signals to tribal offices in Weitchpec, but service is sporadic. Two elementary schools have only radio phones, which isn't effective. There's no 911 for emergencies, no pediatrician on call to talk over a child's sudden fever. A medical emergency, or even a simple change in travel plans means a long trip over one-lane, unpaved roads. "People can't relate to that," says Sue Masten, the Yurok Tribe's chairwoman, who has worked on the issue of the American Indian digital divide as president of the National Congress of Indian Affairs. In 1998, there was a telephone in 79 percent of the nation's poorest households (annual income less than $5,000). For the 48 largest American Indian reservations -- including all income levels -- the rate was 47 percent. Part of the problem is that many reservations are remote, with poor roads and rough terrain where telephone companies are reluctant to venture. Farmers, ranchers and other people living in isolated areas also often wait years for phones. Some companies offer service but require people to pay thousands of dollars to lay their own line. Meanwhile, some reservations may not push for phone service because they've been taken advantage of in the past by fly-by-night companies or because they distrust or don't understand the telecommunications bureaucracy. The digital disconnect shows up sharply in classrooms. "Most of these little Indian schools don't have a very big library. So if the bigger city kids are looking up the Louvre on the Internet and our kids have never even been to a museum, there's a big disadvantage," says Buller. The 1996 Telecommunications Act directed the Federal Communications Commission to ensure that all Americans have affordable phones, and there are two federal programs for poor people that subsidize installation and basic phone service. But even with high-level intervention, progress has been slow. Then-President Clinton went to Arizona to publicize the case of a 14-year-old Navajo girl who won a computer from a now-defunct Silicon Valley dot-com, but didn't have a phone line to make an Internet connection. Myra Jodie finally got connected only this year, when San Jose-based Globalstar, a satellite phone business, installed the equipment and agreed to pay the $1-a-minute charge for at least a year. Some tribes have gone into telecommunications themselves. In the Gila River Indian Community of south-central Arizona, only one out of six homes had phones when the tribe formed its own Gila River Telecommunications Inc. in 1988, says company spokeswoman Jean Harmon. Today, they have more than 3,800 lines and three out of five homes on the reservation have service. A few tribes are crossing the digital divide themselves. In Oklahoma, the Cherokee Nation, many of whose members live in or near urban areas, runs an information-packed Web site, complete with a downloadable Cherokee language font. Last year, the tribe broadcast its chairman's "State of the Nation" speech in streaming audio over the Internet. The tribe is working on interactive language software and plans to establish high-power T1 lines to eight sites to speed up computer connections between tribal members scattered over 14 counties. "The way to keep a language and culture alive is to adapt to the new technology," says Cherokee spokesman Mike Miller. "There's not a lot of Cherokee-owned television." Thanks to the PUC, basic phone service is now tentatively promised within the next two years to 37 more homes on the Yurok reservation, the two schools and a Head Start center, two community centers and a health clinic. Most of the new connections will be on Yurok land, but the Hoopa tribe hopes to eventually tap into a new fiber optic cable that's being laid through their land. The deal's not final yet. In July, Citizens filed a petition before the commission objecting to some financial terms of the sale. The tribes expect to learn the outcome of the petition within the next few months. |

|

|

|

National Congress of Indian Affairs |

|

National Indian Telecommunications Institute |

|

Gila River Telecommunications, Inc. |

|

Government site |

|

Cherokee Nation |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||