|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

August 25, 2001 - Issue 43 |

||

|

|

||

|

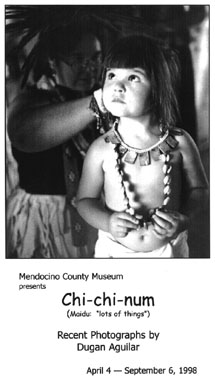

Reflections of a People: Keeper of the Flame -- For Dugan Aguilar, photographing the lives of California Indians is in his blood |

||

|

by Victoria Dalkey Sacramento Bee Correspondent-August 19, 2001 |

Dugan Aguilar

sat on a bench in the Crocker Art Museum, where a show of his photographs is on view, and told me how he captured

an unusual image of a coyote spirit. The photograph is of an inverted landscape that looks, when turned sideways,

like the mythic trickster god in a headdress, with his hands on his hips, just as he appears in American Indian

dance ceremonies. Dugan Aguilar

sat on a bench in the Crocker Art Museum, where a show of his photographs is on view, and told me how he captured

an unusual image of a coyote spirit. The photograph is of an inverted landscape that looks, when turned sideways,

like the mythic trickster god in a headdress, with his hands on his hips, just as he appears in American Indian

dance ceremonies. "There had been a death in the family," Aguilar recalled, "and I went up to Mount Lassen, which is sacred to our people, for a week. The coyote is a sign of impending death for us, and the first night at dusk, while I was burning angelica root, some coyotes came to scavenge in the garbage cans in the parking lot. "It was summer and there was snow. The lake was clear and calm. I had my headlights on and I took one exposure as a coyote streaked across my lens. When I developed it, the coyote didn't register. It was too dark and the exposure was too long. So I lost him. "The next day I went back to the same place just as the sun was setting, lighting up Mount Lassen. The lake was real still, like glass, and I took another exposure. It was a horizontal shot of the mountain and lake, but when I was developing it, I had it placed vertically in my small sink. And there was my coyote." (The photograph is mounted vertically in the exhibit.) Just as Aguilar finished the story, a museum guard approached us and said, "There's been an earthquake, and you will have to leave the building." "Coyote," Aguilar said, shaking his head and flashing his deep dimples. A shy, self-effacing man, Aguilar has built a quiet reputation as one of the foremost photographers of California Indians. His poignant, introspective photographs of family members, basket weavers and ceremonial dancers have been shown at the British Museum, Princeton University and the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City, as well as in numerous museums and galleries in California. Aguilar's images, noted Crocker curator Scott Shields, "are understood not only as portraits of Native Americans but as portraits of humanity." One has only to look at his powerful photograph of Adam Enos, a 3-year-old Maidu Indian in costume, to see the truth of that. The child, with chubby bracelets of baby fat around his arms, holding the clapper sticks that make music for the dance, might be an image of the first child, a primeval being that embodies the hope of a people for an unbroken tradition that reaches back to their beginnings. Born in Susanville, Aguilar, 54, is of Paiute, Pit River, Maidu and Irish descent. The name "Dugan" is Gaelic for "one of dark complexion." He comes from a close-knit family proud of its tribal heritage. He grew up participating each year in the Bear Dance Ceremony, held in June to give thanks for making it through the hard winters in the Sierra, where Susanville is situated. Though he isn't a true traditionalist, he reveres the singers, dancers and basket weavers who preserve the language and customs of his people, and he has made ceremonial regalia for his son. "I know the feel and smell of splitting the willow and the buckskin," he said. "In another lifetime, I would wish to be a singer, someone who works to retain the language, or a weaver. "In a sense," said Aguilar, who works as a graphic artist in The Bee's advertising department, "I live in two worlds -- the Indian world and today's society -- and I'm pretty much in harmony with both." The first college graduate in his family, Aguilar received a degree in industrial technology and design from California State University, Fresno, in 1973 and subsequently took photography classes at the University of Nevada, Reno. A visit to an Ansel Adams exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco in 1973 confirmed his desire to be a photographer. "I walked in and saw Adams' photograph of aspens, printed 30 by 40 inches. It was gorgeous from 50 feet away, and as you approached, you felt like you were walking into the photograph. Up close, the whites and the shadows were so impressive. I decided to strive for being that kind of printer. That was the goal I set for myself and I finally feel I'm a decent printer." Adams' influence is apparent in Aguilar's beautifully printed shots of a canyon in Death Valley, ocean rocks in Monterey and a richly textured, silvery-toned image of a rock formation called Stone Mother at Pyramid Lake in Nevada. Like Adams, Aguilar previsualized his stunning shots of teepee poles against a dark sky, created by using a red filter, and a kiva ladder at the Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico. In the latter, the protruding points of the ladder, printed so precisely that you see each detail of the wood grain, have been cropped and isolated against the sky, emphasizing the spiritual role of the ladder in keeping evil spirits away from the kiva. Similarly spiritual in nature is an almost abstract shot of the roundhouse at Chaw'se in Indian Grinding Rock State Historic Park, taken from the floor of the fire pit, so that the poles of the roundhouse against the white sky form an image that might be the sun and its rays. Strong as his photographs of the landscape and Indian structures are, Aguilar has a special knack for photographing people. His portraits began as a way of documenting his own family and then grew into a document of a whole Indian community, centered around basket weaving and ceremonial rituals. From the innocent charm of young basket weaver Amanda Carroll to the strength and wisdom of Lena Servillican, an Indian musician he met at the Stewart Indian School in Carson City, Nev., his portraits of native people are images of joy and dignity. A shot of three Maidu dancers, one with beads covering her eyes, serves as a precious document of Maidu ceremonies. Part of Aguilar's family history is encompassed in a shot of his uncle, Leonard Lowry, who was the most decorated American Indian World War II veteran, riding in a Thunderbird convertible. The candid shot captures the pride his uncle took in being the grand marshal of the Lassen County Fair. The historic mural behind the car contains images of Chief Winnemucca and Susie Evans, Lowry's grandmother, who was an Indian doctor, tying him to the past of the region. Basket weavers hold a special place in Aguilar's heart. Several of his family members are weavers, and the show includes his photographs of them along with baskets they have made. These are part of a larger exhibition of California Indian baskets mounted in conjunction with Aguilar's photographs and the narrative paintings by his cousin Judith Lowry, which are also on view at the Crocker. Many of his images of weavers are included in the book "Weaving a California Tradition," published in 1996. From a shot of two ebullient weavers in basket hats sharing a humorous moment at a meeting of the California Indian Basket Weavers Association, to a radiant profile of weaver Jene McCovey, some of his strongest images focus on those who carry on an ancient tradition, gathering natural materials and turning them into baskets with geometric patterns that speak to Aguilar's soul. "Those patterns are in my blood," he said. "I have learned a lot from the weavers. They don't work on baskets unless everything is right and feels good. They introduced me to white sage, which I burn now before going into the darkroom. "The real art of photography lies in the printing. Everything affects me when I am doing it, from the quality of the paper to the music I am listening to." Aguilar's intuitive approach to photography becomes clear when he describes his method of taking a portrait. Rather than "taking" a picture, he waits for his subjects to "give" him a picture. "When you look through the lens," he said, "sometimes you find people have built a wall around themselves. To break that you have to be ready for them to give you their image. You wait for the decisive moment." The photograph of Amanda Carrol came about because Amanda's grandmother, a celebrated weaver, was too shy to break that wall. Instead, she let Aguilar photograph her granddaughter, who opened herself to the camera and gave him an unforgettable image. "I'm honored to have gained the trust of the Indian community," said Aguilar. "Every day I learn something new about my culture and my people. It's a gift." |

|

Crocker Art Museum |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||