|

On a Friday in May, Helen Rush Robinson of the Nuu-chah-nulth people of Canada, joined

relatives and other members of the tribe for a long trip to Vancouver.

It was the first step on their journey from Port Alberni, on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, to New York

to retrieve an artifact important to the Nuu-chah-nulth and even more dear to Robinson: a painted curtain that

her father, a chief of the Uchucklesaht band, had commissioned for her coming-of-age ceremony nearly 60 years ago.

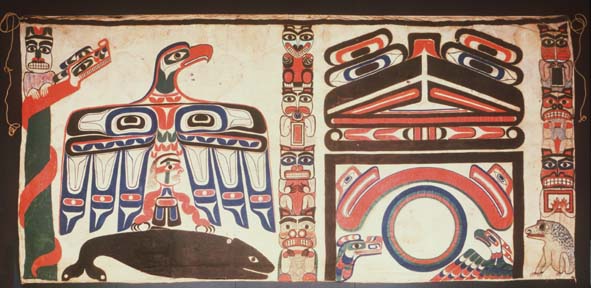

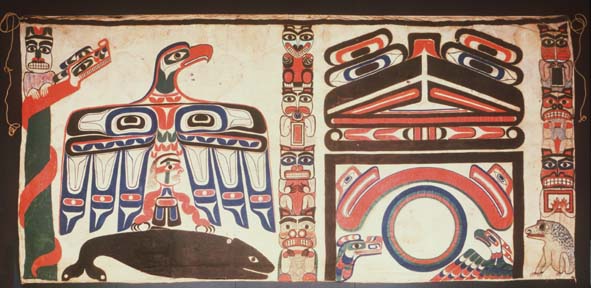

She had never forgotten the huge painted curtain attributed to the artist Tomiish. It showed a thunderbird filling

the sky, serpents flanking it breathing lightning and a whale roaring thunder. It had disappeared from a closet

in her attic shortly after her father's death in 1963.

"For the Nuu-chah-nulth people, painted curtains are the most important artworks," said Alan Hoover,

manager of the anthropology department at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria before retiring last month.

He helped organize "Treasures of the Nuu-chah-nulth Chiefs," a two-year traveling exhibition of painted

curtains and other artifacts that ended last month in Los Angeles.

That exhibition brought about the discovery of Robinson's curtain. George Terasaki, a retired New York dealer of

Indian art, had lent three curtains to the exhibition and told Hoover about three others that he owned. Hoover

passed the information along to the Nuu-chah-nulth tribal council, and one of the curtains was identified as Robinson's.

Terasaki said that when he bought the curtain 30 years ago it came without any historical documentation.

"That curtain is like a book of family history," Robinson said. "It holds the proof of who I am.

There are songs that go with the curtain that tell all the family stories."

Robinson appeared in April with other members of the Uchucklesaht band at a meeting of the Nuu-chah-nulth tribal

council, a body that represents 7,500 people in 14 nations, to ask for help in acquiring the curtain at the price

Terasaki asked: $17,000.

Several young women rose immediately to pledge support from different bands among the 14 nations. George Watts,

the chairman, asked that each nation contribute $2,000 in Canadian currency to pay for the curtain, and all agreed.

NEW YORK On a Friday in May, Helen Rush Robinson of the Nuu-chah-nulth people of Canada, joined relatives and other

members of the tribe for a long trip to Vancouver.

It was the first step on their journey from Port Alberni, on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, to New York

to retrieve an artifact important to the Nuu-chah-nulth and even more dear to Robinson: a painted curtain that

her father, a chief of the Uchucklesaht band, had commissioned for her coming-of-age ceremony nearly 60 years ago.

She had never forgotten the huge painted curtain attributed to the artist Tomiish. It showed a thunderbird filling

the sky, serpents flanking it breathing lightning and a whale roaring thunder. It had disappeared from a closet

in her attic shortly after her father's death in 1963.

"For the Nuu-chah-nulth people, painted curtains are the most important artworks," said Alan Hoover,

manager of the anthropology department at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria before retiring last month.

He helped organize "Treasures of the Nuu-chah-nulth Chiefs," a two-year traveling exhibition of painted

curtains and other artifacts that ended last month in Los Angeles.

That exhibition brought about the discovery of Robinson's curtain. George Terasaki, a retired New York dealer of

Indian art, had lent three curtains to the exhibition and told Hoover about three others that he owned. Hoover

passed the information along to the Nuu-chah-nulth tribal council, and one of the curtains was identified as Robinson's.

Terasaki said that when he bought the curtain 30 years ago it came without any historical documentation.

"That curtain is like a book of family history," Robinson said. "It holds the proof of who I am.

There are songs that go with the curtain that tell all the family stories."

Robinson appeared in April with other members of the Uchucklesaht band at a meeting of the Nuu-chah-nulth tribal

council, a body that represents 7,500 people in 14 nations, to ask for help in acquiring the curtain at the price

Terasaki asked: $17,000.

Several young women rose immediately to pledge support from different bands among the 14 nations. George Watts,

the chairman, asked that each nation contribute $2,000 in Canadian currency to pay for the curtain, and all agreed.

NEW YORK On a Friday in May, Helen Rush Robinson of the Nuu-chah-nulth people of Canada, joined relatives and other

members of the tribe for a long trip to Vancouver.

It was the first step on their journey from Port Alberni, on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, to New York

to retrieve an artifact important to the Nuu-chah-nulth and even more dear to Robinson: a painted curtain that

her father, a chief of the Uchucklesaht band, had commissioned for her coming-of-age ceremony nearly 60 years ago.

She had never forgotten the huge painted curtain attributed to the artist Tomiish. It showed a thunderbird filling

the sky, serpents flanking it breathing lightning and a whale roaring thunder. It had disappeared from a closet

in her attic shortly after her father's death in 1963.

"For the Nuu-chah-nulth people, painted curtains are the most important artworks," said Alan Hoover,

manager of the anthropology department at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria before retiring last month.

He helped organize "Treasures of the Nuu-chah-nulth Chiefs," a two-year traveling exhibition of painted

curtains and other artifacts that ended last month in Los Angeles.

That exhibition brought about the discovery of Robinson's curtain. George Terasaki, a retired New York dealer of

Indian art, had lent three curtains to the exhibition and told Hoover about three others that he owned. Hoover

passed the information along to the Nuu-chah-nulth tribal council, and one of the curtains was identified as Robinson's.

Terasaki said that when he bought the curtain 30 years ago it came without any historical documentation.

"That curtain is like a book of family history," Robinson said. "It holds the proof of who I am.

There are songs that go with the curtain that tell all the family stories."

Robinson appeared in April with other members of the Uchucklesaht band at a meeting of the Nuu-chah-nulth tribal

council, a body that represents 7,500 people in 14 nations, to ask for help in acquiring the curtain at the price

Terasaki asked: $17,000.

Several young women rose immediately to pledge support from different bands among the 14 nations. George Watts,

the chairman, asked that each nation contribute $2,000 in Canadian currency to pay for the curtain, and all agreed.

|