|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

August 25, 2001 - Issue 43 |

||

|

|

||

|

Reading Dr. Seuss in Mutsun |

||

|

by Robin Shulman LA Times Staff Writer-August 13, 2001 |

MADERA,

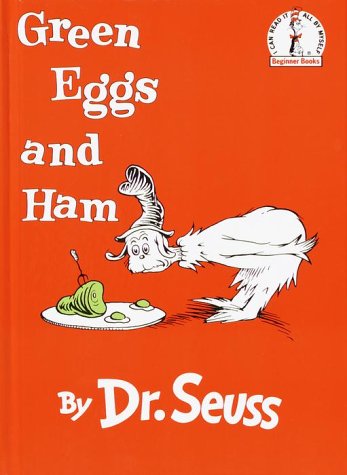

Calif. -- Quirina Luna-Costillas is reading Dr. Seuss to her three children at the dining-room table. She turns

the pages of "Green Eggs and Ham," holding up the familiar pictures of Sam I Am and his odd-color breakfast. MADERA,

Calif. -- Quirina Luna-Costillas is reading Dr. Seuss to her three children at the dining-room table. She turns

the pages of "Green Eggs and Ham," holding up the familiar pictures of Sam I Am and his odd-color breakfast.

But she does not speak the familiar staccato rhyme. She has blocked out the English words, and reads instead from text she has Scotch-taped on top. "Samka Am. Kan Am Sam," she says in Mutsun, a language last spoken fluently by a San Juan Bautista-area Indian in 1930. The children, ages 10, 6 and 2, jostle one another as Luna-Costillas points to green eggs. "What color is that?" she asks. "Tcutsu!" 2-year-old Jonathan answers in the language of his great-great-great-grandparents. Luna-Costillas is a 30-year-old Mutsun Ohlone Indian who grew up in California's Central Valley. She has spent five years piecing together her people's lost language from century-old grammar texts, various transcripts and wax recordings--in her spare time, while working as a cashier. She has been teaching Mutsun to her children in hopes that they will pass it on. Jonathan may have been the first child in 100 years to say his first word--tatay, or "touch"--in Mutsun. "We thought the language was dead," said Luna-Costillas, who recalls her fourth-grade textbook declaring local Indian languages and people extinct. But five years ago, she began attending regional tribal gatherings and learned the Mutsun people were alive and well, their language merely dormant. It slept in the notes of missionaries, and of anthropologists and linguists who transcribed the stories and rituals, games and songs of Mutsun speakers. And in wax cylinder recordings, early audio discs that disintegrate each time they are played and are useless after half a dozen hearings. Luna-Costillas has awakened the language in everyday phrases at home. Amaniti. Come and eat. Ani hotoh. Where are your shoes? She is working with linguist Natasha Warner to create an English-Mutsun dictionary, a textbook for children and translations of stories and songs. And she teaches Mutsun at tribal gatherings. Mutsun is not the only Native American language being revived. From Arizona to Alaska to Hawaii, tribes are videotaping elders speaking languages that they are the last to know. Speakers are giving classes by long-distance telephone. In school immersion programs, children are learning languages that their grandparents were the last generation to speak. Congress in 1990 passed the Native American Languages Act, which translated into money for language renewal projects all over the country. That year, the National Parks Service gave nearly $15 million to Native American cultural preservation efforts, which include language study. The Administration for Native Americans awarded $2.5 million to language projects last year, and this year expects to double that sum. But despite the new attention to saving these languages, chances are dismal that many will survive, experts say. Throughout the country, about 175 are spoken, according to 1999 Senate testimony by Alaska linguist Michael Krauss. But only a very few are spoken by enough young people to give them a chance at survival. In 60 years, Krauss predicted, only 20 Native American languages will be left. In California, where about 30 Indian languages have fallen out of use, more than 15 besides Mutsun are being resurrected, linguists say. In Woodland, near Sacramento, a woman learned Rumsien songs from recordings of her great-great-grandmother's voice. Another woman is developing a CD-ROM to teach Ajachemem, once spoken in Orange County. A statewide program run by Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival has paired 65 elders with "apprentices" studying 20 languages. Some tribes with gambling operations donate part of their casino proceeds to language instruction. And a summer workshop at UC Berkeley gives California Indians a crash course in linguistic notation and research. Lost Language, Lost Knowledge "Posterity loses when you lose a language," said UC Berkeley linguist Leanne Hinton, who runs the workshop. "You lose the diversity of human thought and human knowledge and human experience. You're not just losing a bunch of words." Luna-Costillas knows that well. She grew up in Madera, traveling to Hollister and Gilroy to pick apricots and grapes with a clan that included her parents and five brothers and sisters. She knew she was Indian, not Mexican like the other children. The others had Spanish to affirm their identity; she had nothing more tangible than her grandmother's herbal remedies. In 1996, searching for a better sense of her history, she attended a few Native American gatherings in the Bay Area and met people who were learning dormant languages. They told her Mutsun had been preserved in written texts. She found a book on the Mutsun people of the San Juan Bautista Mission by missionary Felipe Arroyo de la Cuesta, who kept notes including 2,884 Mutsun phrases. She spent hours committing the words to memory and perusing other records. The Mutsun, scholars say, come from land that stretches from the San Joaquin River west to the coast, and north from Morgan Hill to Soledad. About 200 Mutsun people live in Madera, Luna-Costillas says; 400 or so remain in the San Juan Bautista area, near the mission built in the late 1790s. While Native Americans labored in the missions, they were forced to learn Spanish and abandon their languages. A woman named Ascencion Solorsano was apparently the last fluent Mutsun speaker; the language was thought to have died with her in 1930. Luna-Costillas took vacation time to enroll in the Berkeley workshop. She and Warner worked from a 1977 dissertation on Mutsun grammar by Berkeley linguist Marc Okrand, who used his work as the basis for the Klingon language he made up for the "Star Trek" series. Luna-Costillas had trouble deciphering Okrand's jargon, so the next year, she enrolled in a linguistics class at Fresno City College. She began to write words on index cards and stick them in her apron at work so she could practice in spare moments at the checkout stand. She learned enough to sing Mutsun songs at a cousin's funeral. And she taught the words to her two oldest children. When Jonathan was born, she spoke to him in Mutsun. Translating "Green Eggs and Ham," Luna-Costillas filled in the blanks as best she could. Could you, would you on a train? "We didn't know what to use for train. So my cousins said, 'Let's do "snake-like," because it's long.' So we used lisana--snake--and putka--like." Would you? Could you? In a car? "When cars came, the Mutsun people used the Mexican word for car, maquina. So we went ahead and used it: Maquinateka. In a car." Last year, Luna-Costillas quit her job and got one as a monitor ensuring that Indian remains and artifacts are not disturbed at construction sites. On rainy nights, she huddled in her Toyota truck with the light on, poring over Mutsun texts. Luna-Costillas knows her children are the best bet for preserving the Mutsun language. But she says she won't pressure them, and it has been hard to keep her two oldest, who live part time with her former husband, interested. Luna-Costillas' parents can't really speak Mutsun, but they try, especially when they baby-sit for their grandchildren. "To see your grandchildren tell each other something in the language that was never spoken--could never be spoken--" Lillian Luna says over the phone with obvious emotion, "--the baby being asleep and waking up and saying something in Mutsun without being told to say it." "It's something they took away," says her husband, Ruben Luna, who is holding back tears. "They couldn't use it in the missions," he said. "It's very important. Quirina is bringing it back." |

|

|

|

|

|

Costanoan-Ohlone Indian Canyon Resources |

|

Mutsun Foundation |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||