|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

August 11, 2001 - Issue 42 |

||

|

|

||

|

Mohegans Rebuilding Language |

||

|

by William Weir The Hartford Courant-July 29, 2001 |

||

|

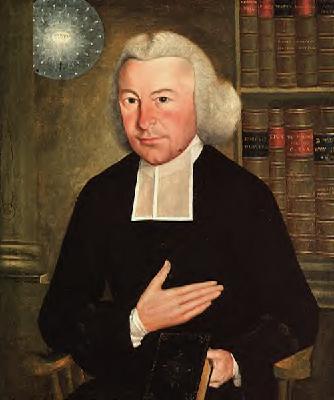

portrait of Ezra Stiles |

UNCASVILLE,

CT - Fidelia Fielding, the last fluent speaker of the Mohegan language, died in 1908. Since then, echoes of the

language have faded into obscurity. UNCASVILLE,

CT - Fidelia Fielding, the last fluent speaker of the Mohegan language, died in 1908. Since then, echoes of the

language have faded into obscurity.But a combination of detective work and what could be called linguistic forensics have helped the tribe and a team of scholars reconstruct the language, word by word. It's a daunting task, but one that tribal elders say is worth the effort because resurrecting the Mohegan dialect is critical to restoring the tribe's sense of identity. The effort began in earnest about three years ago, but had stalled until a key discovery earlier this year at Yale University's Beinecke Library. There, linguistics researcher David Costa found a cache of documents about Mohegan life and language compiled by, among others, Ezra Stiles, an 18th-century theologian and scientist who was Yale's second president. Everything then fell into place. "We were going crazy, doing this Sherlock Holmes thing, trying to find the Ezra Stiles documents," said Beth Lee MacDonald of Big Head Interactive, a California production company that is helping the tribe put together lesson plans for teaching the language. Tribal elders say the ultimate goal is to bring the language back into Mohegan homes and everyday conversation. At the very least, it will be used in ceremonial settings. "I think that the relationship between language and culture is so interconnected," said Gay Story Hamilton, chairman of the tribe's council of elders in Uncasville. "We want to get back some of what we had." In the past few years, the Mohegans have built up both the financial resources and the sense of community needed to make such an ambitious goal realistic, if not a guaranteed success. Close to a year ago, the tribe members believed the bulk of their language work was done and had begun developing formal lesson plans. But they soon discovered serious inconsistencies in the material, and the project came to an abrupt halt. Most of the original research was based on the diaries of Fidelia Fielding, which were long believed to be the only Mohegan writings left. Fielding, who served as tribal culture-keeper, was born in 1827 and lived in both pre-reservation and post-reservation eras of Mohegan society. Because no one else could converse with her in the language for the last 50 years of her life, her skills were increasingly influenced by English-speaking peers, corrupting the sentence structure and vocabulary of her later writings, Hamilton said. Costa, formerly of the University of California at Berkeley, was hired by Big Head Interactive in January this year. He remembered another researcher mentioning the Stiles documents at Beinecke and saw references to them in his materials. Costa and Beinecke's librarians spent hours searching before they were able to finally produced a file that included Stiles' accounts of Mohegan life and translations of about 150 Mohegan words, accompanied by a somewhat spotty pronunciation key. Further searching produced an even more valuable document: notes jotted on the blank pages of a book called "Almanac of Celestiall Motions of 1669." The notes, written by James Noyes, a 17th-century minister from Stonington, provided a vocabulary key and more accurate pronunciations for about 300 Mohegan words. Costa is also working from writings of other Algonquian tribes, such as the Narragansett and Wampanoag, to help him identify patterns and make the appropriate changes to fill in gaps in the Mohegan language. For instance, a word in the Natick dialect of the Wampanoag Indians of Massachusetts that contains a "Y" would likely be the same in Mohegan, but with an "N" instead of the "Y." Languages of the Unquachog or Nipmuck Indians would use an "L" or "R" in the same place. "They're very close to Mohegan," he said. "Just a small handful of changes are needed to get from one dialect to another." Costa has headed up language restoration projects with a few tribes throughout North America, most recently the Miami tribe of Oklahoma. Interest in reviving the languages began to surge about five years ago, he said, when it became apparent how quickly they were dying. By some counts, about 100 American Indian languages remain, many of which are spoken by just a handful of people. When Columbus arrived on the continent, there were more than 300 Indian languages. More than just a relic of a past era, language serves as a window to its speakers' world view. The Mohegan language, Costa said, categorizes all nouns as either animate or inanimate. For instance, all the limbs of a body are considered animate, but the body itself is inanimate. Many of the languages died as a result of policies of both the U.S. government and of certain tribes that either prohibited the teaching of American Indian languages or strongly discouraged it. Languages became even more endangered after World War I, when tribes became less isolated. Despite her wish to speak in Mohegan with others, Fidelia Fielding never passed on her knowledge for fear that any proteges would suffer reprisals for speaking the language. Tribal officials at the time believed assimilating into English-speaking culture was the best thing for American Indians. Hamilton, who serves on the board of directors of Yale's Endangered Language Fund, believes television to be among the biggest obstacles to restoring the language. Most homes, including those of tribe members, have at least one television. Reviving the Mohegan language doesn't mean shutting out English-speaking culture altogether, Hamilton said, but vigilantly staying in touch with their own. The tribe expects the restoration research to be complete by fall. A formal curriculum for teaching it will then be developed. Tribe members will act out skits to be filmed for audiovisual CD-ROMs, which will be used in language classes. Lessons will also be taught at day-care facilities on the Mohegan reservation. Because of the long dormant state of Mohegan language, there will be some gaps. New words for anything that has come along since Fidelia Fielding's time will be based on descriptions of the thing or idea in question. For instance, a word for "computer" might translate literally to "thought keeper." The language has already made its way into the tribe's administrative offices. Employees routinely greet each other with "tôn kutaya?" ("how are you?") and voice mail messages begin with "aquy" ("hello"). But the key to restoration, tribal officials say, is getting children interested. Shane Long, the tribe's cultural outreach director, is encouraged by his daughter's apparent aptitude for Mohegan and hopes other children will be equally eager to learn the language. Jessica Long is, as she'll cheerfully tell you, "pásukokun," which means that she's 9 years old. Though she's hardly fluent in the tribe's language, Jessica is learning quickly and is already pretty good with numbers and a few phrases. Long is going to keep at it, but admits his own attempts to learn Mohegan have been tentative. "It's tough for me," he said. "The language is so completely different from what I know." |

|

|

|

Endangered Language Fund |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||