|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

June 30, 2001 - Issue 39 |

||

|

|

||

|

Inuktitut: The Future of the Language |

||

|

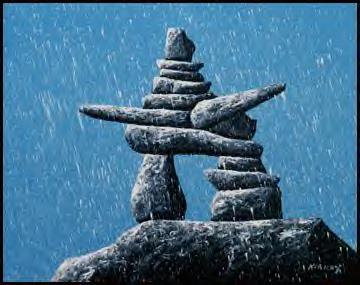

art: Still Standing by Ken Kirkby |

The students at Joamie Elementary School in Iqaluit start every day in the

same way. As the sun rises over Frobisher Bay, they step in from the frigid weather, take their coats and boots

off, and head to the gymnasium to sing Oh Canada. The students at Joamie Elementary School in Iqaluit start every day in the

same way. As the sun rises over Frobisher Bay, they step in from the frigid weather, take their coats and boots

off, and head to the gymnasium to sing Oh Canada.But here, the national anthem begins like a traditional Inuit song, and it's sung in Inuktitut. Many of these children are taught exclusively in Inuktitut until grade four. Some learn it for even longer. But by the time these students are old enough to head across town and attend Inuksuk High School, they won't be learning Inuktitut at all. Students who currently go to Inuksuk High think the education system is letting them down. They want to learn Inuktitut, just like in elementary school and some of the smaller communities. But the courses are not offered. Recently on CBC Radio, a panel of teenagers from Iqaluit spoke about this, as part of Nunavut's Language Week. "In Arctic Bay, in junior high, from elementary to junior high they did Inuktitut. And then in high school they taught English. I liked it in Arctic Bay because we did more Inuktitut work than here. Here we do nothing. "They don't teach us Inuktitut. The language in five or ten years, I don't think we're going to have it anymore, because the way we're going right now, having no teachers or having teachers that can't teach, we're not going to have it. "I see the language fading away but in the smaller communities, where it's really strong, they can keep it. But here it's not spoken or taught, and we're just going to lose it." Glancing around the town of Iqaluit, it wouldn't appear that the language is fading away. Stop signs are written in Inuktitut. Same thing for storefronts, like the banks and the post office. And turn on CBC Radio - much of the programming day is in Inuktitut. Not only that, but people who move here from southern Canada to work for the Nunavut government are now required to learn Inuktitut. The commitment to the language has been a part of government policy since Nunavut was created almost two years ago. Carmen Levi is the government's chief bureaucrat in charge of language. "We're hoping that everyone who works for the Nunavut government will be fluent in Inuktitut. People who are coming from the south and start working for the government are already taking Inuktitut as a second language, so that they're able to converse a little bit in Inuktitut." Levi knows this will take time. The government has given itself twenty years to make everyone bilingual. But many others say the government is not acting fast enough. Nunavut's Languages Commissioner, Eva Arreak, hears the complaints of high school students, and thinks Inuktitut is already in trouble. "It's when you enter the high school stage that you see the departure of your language and culture. This is especially evident in larger centres. Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet, Cambridge Bay. Although there has been a lot of talk lately of enriching and enhancing Inuktitut in the schools, it's not happening fast enough." Arreak thinks that if the government doesn't make Inuktitut a priority in high schools now, then the language will slowly slip away. But others see an even more telling sign that Inuktitut is in trouble. Mick Mallon moved to Canada's Eastern Arctic from Northern Ireland about forty years ago, and has been teaching Inuktitut for decades. In his opinion, the true test of a language's strength is what happens in Iqaluit's homes. "The language on the surface would appear to be quite strong. But I just got a book on how languages die. It starts like a cancer and spreads. And it normally starts in the capital cities. There are signs here in Nunavut that we don't need to be complacent about the language. Some kids speak it and many adults speak it, and that's a base. But it's the home. If the parents don't insist that Inuktitut be the language of the home, then the prospects of the language continuing are very dim." This is the sort of talk that frightens many people here. Inuit watched their language almost disappear once before. In the 1950s and 1960s, when young Inuit were forced into Residential Schools, they had to speak English. Many forgot Inuktitut entirely. Eva Arreak, the languages commissioner, was one of the many people forced to speak English at school. "What I missed was my own language and culture in the place where I was all day. From being outside, you go into the classroom and, especially in the wintertime, you take your hat off, your coat off, your boots off. It's like taking your culture off at the door. Because you're going to be in th is room learning an entirely different culture and language. And at the end of the day you put your hat on and your coat on and your boots on, and you are back to where you feel comfortable." Arreak managed to retain her first language, Inuktitut. But the very idea that it could disappear entirely is a scary one for her, because she knows what would disappear with it. "Who are you if you don't have your culture? How do you feel? How do you see yourself? If you know who you are, if you know your language, your culture, if you know where you came from, then you are that much more confident in yourself, and you are ready to take on the challenges of life." For the students, even singing Oh Canada in Inuktitut every morning at school is a dream come true. It wasn't that long ago when Inuit almost lost their language entirely. But the creation of Nunavut two years ago has inspired them to expand the dream. Nunavut has given Inuit control over their own affairs. They plan to use this new authority to preserve and enhance Inuktitut, because they know that if the language dies, the dream will too. |

| Locate the Territory of Nunavut on the map! |

|

|

|

Joamie School |

|

Inuksuk High School |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |