|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

June 2, 2001 - Issue 37 |

||

|

|

||

|

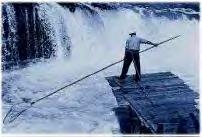

Salmon in our Heritage |

||

|

by Rocky Barker The Idaho Statesman |

Viola Anglin

knew the salmon had returned to the Lemhi River when she saw their tails had swept the moss off the base of the

old Mahaffey Bridge. Viola Anglin

knew the salmon had returned to the Lemhi River when she saw their tails had swept the moss off the base of the

old Mahaffey Bridge. The salmon runs used to attract hundreds of anglers who crowded into Anglin's Tendoy Store, 20 miles east of Salmon, Idaho, where both the city and the river are named for the fish. The fishermen accounted for most of the profit margin of the store that Anglin, 81, has owned since 1948. "We had so many friends from all over the countryside," Anglin said. "It's been gone for a long, long time." Dwindling returns brought the end of salmon fishing on the Lemhi in 1972. This summer, thanks to ideal migrating and ocean conditions, the fish are swimming up Idaho rivers in the highest numbers since the 1950s. Right now, Idahoans have the chance to experience the kind of salmon runs that imprinted on our culture and helped shape our history. Signs of salmon culture are all around us. We call our hockey team the Steelheads (an ocean-going relative of the salmon). Art students make salmon sculptures. Meridian elementary kids paint pictures of the fish. It's what's for dinner in many homes year-round. And this year, salmon will even return to the Boise River, for only the second time since the 1950s, with the help of Idaho Fish and Game's salmon trucking program. "I think we will have a much greater opportunity to experience a historical part of salmon history and culture that was more widespread 100 years ago," said Sharon Kiefer, Idaho Department of Fish and Game salmon and steelhead fisheries manager. How it started The Northwest's cultural connections to fish began at least 12,000 years ago as early American peoples used the fish for physical and spiritual sustenance. The value of the fish was passed into Anglo culture when Shoshone Indians first fed salmon to legendary explorer Merriwether Lewis in 1805, near the site of Anglin's store at the base of Lemhi Pass. During the past century, new hydropower projects were needed to keep pace with industrial growth. Sen. John Sandy, R-Hagerman, comes from a family of sheep ranchers. He spent his summers in the 1950s and 1960s at the headwaters of the Middle Fork of the Salmon River, where his family grazed bands of sheep. As a child, he would try to catch the big spawners by their tails in Marsh and Knapp creeks; or he would try to revive the dying fish after they spawned. Most dramatic was watching the huge fish leap high to climb over Dagger Falls. "I can remember my parents telling me these fish had come all the way from the ocean, and I'd never seen the ocean," Sandy said. But slowly and steadily, man-made obstacles cut off salmon from their spawning grounds. And as the fish slipped away, so did many of Idahoans' cultural ties. No fish, no fishing. The only place in Idaho people regularly fished for salmon after 1978 was below the Rapid River Hatchery on the Little Salmon River. Even that was not very successful. Thrown together in a small area, tribal and other anglers clashed over the few fish that could be caught. The future looked bleak for salmon when, in 1990, the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes petitioned the federal government to list Idaho's sockeye salmon as endangered. Suddenly the fight over salmon was in the newspapers and on TV. Protesters in salmon suits marched up the Capitol steps and outfitters paraded their boats through Idaho's cities in support of the fish.  But as salmon advocates have called for breaching dams and limiting irrigation, logging and mining,

many rural Idahoans see it as an attack on their own heritage. Farmers resent the implication that salmon culture

is of greater importance than their own. But as salmon advocates have called for breaching dams and limiting irrigation, logging and mining,

many rural Idahoans see it as an attack on their own heritage. Farmers resent the implication that salmon culture

is of greater importance than their own. "What's happened is the story of American progress in Idaho has a dam in it," said Todd Shallat, a Boise State University history professor. "The salmon fits into this narrative as a symbol of the counterculture. It's the anti-hero." If urban salmon culture has led the movement to save the fish, rural Idahoans in those struggling agricultural economies are starting to figure out ways to turn sentiments for the salmon into dollars for their communities. In Riggins and Orofino, businesses are cashing in on anglers who have flocked to catch the more than 100,000 hatchery salmon that have returned to Idaho this year. Boise sporting goods stores are running out of salmon fishing tackle. Today, tribal fishermen and sport anglers stand side by side on the river along U.S. Highway 95 cooperatively catching their quotas. At Spring Bar on the Salmon River, 10 miles east of Riggins, a group of outfitters, Riggins residents and Nez Perce tribal members held a ceremony together earlier this month to welcome back the salmon. "These fish are more than just an economic value to us," said Gary Lane, owner of Wapiti Outfitters in Riggins. Salmon have always been more than an economic value to the state's Indian tribes. Horace Axtell, a Nez Perce religious leader, sat around a campfire after leading the ceremony and described the role of salmon in his life and the lives of his ancestors. "Water is the most important element of our way of life," he said. "The next element is salmon."  Passing on a tradition Passing on a tradition A new generation also is learning about salmon. Meridian teacher Deaun Zrno vaguely remembers salmon issues in the 1970s and '80s. But they didn't become a part of her life until she attended a Fish and Game teaching workshop in McCall in the mid-1990s. There, she got to hold spawning fish and see them in the Salmon River. "I remember hearing about the construction of dams but didn't think to question the effects they would have on natural resources and the species -- good or bad," she said. Now she has her gifted and talented students hold a "salmon summit," with each taking the role of a different interest, from farmer, to dam operator, to fisherman, biologist or Indian. She wants to help make salmon the part of their life that they never were for her. "I didn't realize what was happening to the salmon, or that I could do anything about it," she said. "They understand salmon and their place in our lives." More than 250 miles from the hustle and pollution of the Treasure Valley, Anglin's son, Kelly, 47, is still involved in the store that supplies the ranches and growing subdivisions east of Salmon. Today he fishes for hatchery-raised steelhead, which continue to return in good numbers, on the Salmon River in the spring and the fall. But he's lost the wild salmon that were so much a part of his youth. "It was very important to me growing up here," Kelly Anglin said. "It's basically how I spent my summers -- looking for a place to fish." Although this year's salmon runs will be the best in decades, Viola Anglin won't share in the economic benefits. The entire Upper Salmon River is off-limits to salmon fishing this year to protect the endangered wild salmon that spawn in rivers like the Lemhi. Twenty-three wild salmon, embedded with computer chips as young fish, have been detected at Lower Granite Dam in Oregon, heading home toward Mahaffey Bridge. Anglin hopes both ranching and salmon survive and continue to be a part of Idaho culture. She hopes to see the moss under the bridge worn away again by the tails of chinook salmon. "I'm getting pretty old, so I can't fish anymore," she said. "I'd love to see them again, though." |

|

Idaho Rivers United |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |