|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

april 21, 2001 - Issue 34 |

||

|

|

||

|

Rice Lake is Priceless to the Chippewa |

||

|

By Melinda Naparalla Special the The Green Bay News-Chronicle |

| Thousands of years ago the Sokaogon Chippewa settled in the Mole Lake area, following

their elders prophecy that their final home would be where food grows on the water. On Rice Lake, the Sokaogon found their food - wild rice. Wild rice has become the lifeblood of the Mole Lake tribe both as food and as a source of income for much of the tribe. Women collect the rice, which grows so thick it looks like wheat, by hand, and it's shucked with birch bark baskets and the wind. But the proposed Crandon mine lies two miles east of the reservation, and the tribe sees its delicate, valuable resource in danger. "Our biggest concern is the possibility of contamination of the wild rice beds," said Roger McGeshick, chairman of the Sokaogon. The small community lacks jobs and many residents live in small houses or trailers. Even a slight amount of acid could destroy the beds, said David Anderson, executive director of a non-profit environmental consulting firm Flintsteel Restoration Association, which does consulting for poor and minority organizations. The firm is doing consulting for the tribe. As far back as 1914, the rice beds were protected, Anderson said. In 1914, the federal Indian agent shut down a logging dam on the Wolf River because it might affect the rice beds. "We lost lives for it before the state existed," Anderson said. "The tribe fought the Sioux to keep the land." The rice beds are respected and revered as an active part of the tribe's oral tradition, Anderson said. "There's a lot of concern over some of what Nicolet Minerals Company is planning to do," McGeshick said. "They say there will be no contamination, but it's hard to say that. What happens if it leaks 40 years down the road?" The tribe has tradition in the area, and tribal members want to see the traditions passed on. "I'd like to see my children have everything I had, and I believe the beds will be contaminated if the mine goes through," McGeshick said. In the '70s, Exxon wanted to mine, and then again in the '80s. Now it's Nicolet Minerals, Anderson said. All of them want to mine the same ore body, which lies upstream of the tribe's waters. "Local landowners can lease their land to the company and move to a different area," McGeshick said. "We can't. We were given the land by the federal government. We aren't going to sell. We can't move our families. We see (Nicolet Minerals Co.) coming in as a government trying to force us out of our homeland. We fought to stay here, and we will." The tribe doesn't know what the future holds for its water and land if the mine is allowed to proceed. If the ground or surface waters were contaminated, the tribe wouldn't be able to use this resource, McGeshick said. The tribe wouldn't be able to eat the fish or drink the water. "I'm an outdoorsman and I fish the lakes near the site. They're crystal clear. I can't imagine pollutants soaking into it," McGeshick said. "I utilize Rice Lake as my dad used it and my uncles and grandfathers used it." According to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the proposed mine site doesn't lie within any of the tribes' reservations, but does lie within ceded territory in which the tribes, by treaty, have guaranteed various fishing, hunting and gathering rights on public land. "We've always been opposed to it," McGeshick said. "Especially as Native American people you just have to look at the history of the tribes, not just in Wisconsin, but across the country. Tribes are pretty much the protectors of the environment and its natural resources." The Crandon issue has shaken the tribe's faith in the Department of Natural Resources. "My job is to protect the reservation, and I don't see the DNR protecting it. If we allow a company like this to come in, I don't see the protection for the citizens of Wisconsin," McGeshick said. "I used to be a conservation warden, and I don't understand the DNR. The DNR is supposed to protect." McGeshick has traveled to various mines in the United States and Canada, many of which had contaminated the environment and hadn't been cleaned up. "I saw the degradation first hand," he said. "I see it as a money issue. They have dollar signs in their eyes. "A big corporation has all the money, but money doesn't mean anything to people here. What's important is their way of life. Water quality is part of their way of life and of ensuring our way of life." He added: "Even though we're small, I'm confident we'll be able to put a stop to the mining issue." The company said it would do everything it could to ensure the protection of the wild rice beds, including regulating the air and water near the reservation closely, said Dale Alberts, spokesman for Nicolet Minerals. The company also will remove pyrite, a metal which becomes acidic when mixed with oxygen and water, from the waste mine ore. The waste water will be treated through a filtration system and then deposited in absorption beds to allow the water to flow through the soil and to re-enter the water table. |

|

|

|

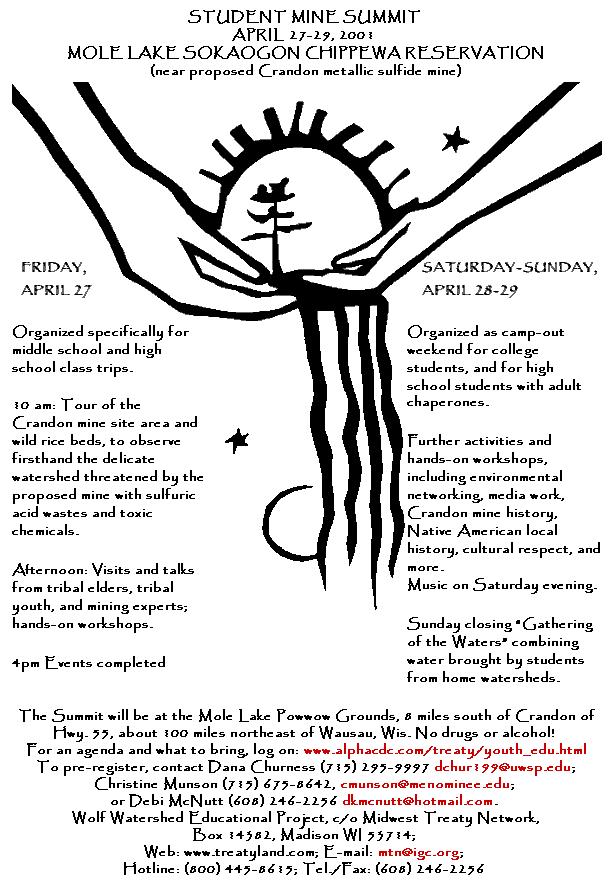

Midwest Treaty

Network |

|

No Mining |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |