|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

april 7, 2001 - Issue 33 |

||

|

|

||

|

The Ways of Tribal Courts |

||

|

BY ELLEN GEDALIUS, Medill News Service |

||

|

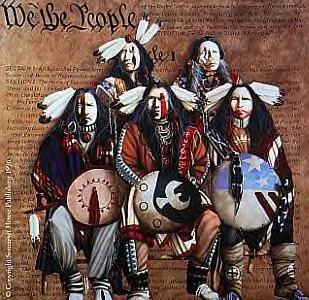

Art We The People by J.D. Challenger |

In the Muscogee

(Creek) Nation tribal court, a medicine man may visit and sprinkle tobacco around the courtroom, purporting to

be able to put hexes on people in an effort to further his cause. In the Muscogee

(Creek) Nation tribal court, a medicine man may visit and sprinkle tobacco around the courtroom, purporting to

be able to put hexes on people in an effort to further his cause.An everyday occurrence? No. But has it happened? Sure, says Muscogee Judge Patrick Moore, who for years has witnessed such tribal traditions seep into his Okmulgee, Okla., courtroom. Yet just because medicine men have made occasional appearances in a Muscogee court doesn't mean they are showing up in tribal courtrooms throughout the country. Tribal lawyers, judges and experts in American Indian law point out that tribal courts are as varied in tradition, appearance and procedure as the tribes themselves. Not even the oath is the same. Some American Indian witnesses take their oaths just as Americans do: raising their hands, sometimes over a Bible. But Kootenai Tribe Chief Judge Fred Gabourie says he has been to courts that have allowed women to spread their ceremonial cornmeal around the witness box and then promise to tell the truth. He also has seen witnesses take their oaths over tobacco leaves. "A lot of them are not Christians and may not swear on the Bible," the Idaho-based judge says. "You may as well swear on the dictionary. Indian people are not going to lie if they put tobacco out." Language usage varies, too, because not all American Indians speak English. In some courts, the various native languages are used to conduct proceedings. In others, such as in the Wisconsin-based Ho-Chunk Nation, English is the dominant language while a few sentences, including the "all rise" and "you may be seated" commands, are said in the traditional tongue. Dress also differs. In some tribal courts, judges wear American-style black robes. Other tribal judges wear long, colorful robes, according to Jill Shibles, executive director for the National Tribal Justice Resource Center in Boulder, Colo. And Ho-Chunk Nation Chief Judge Mark Butterfield wears a black robe adorned with a semblance of the tribe's seal. A beaded medallion drapes Butterfield's neck. Moore, of the Muscogee tribe, says he only wears a black robe when he oversees jury trials. Oftentimes he wears jeans. Rory Flint Knife, his long hair in a ponytail reaching the small of his back, says he feels most comfortable in jeans, too. "It reflects some of your attitudes toward life," the Yakama Nation chief judge says. "(Being a judge) is about whether you can dispense justice in a human sense. So dress like a human." And don't rule out the moccasins. Or the artifacts, which give some courts look of museums. Paintings of key legal figures often line the walls of state and federal courthouses. In many American Indian courts, depictions of important Indians hang. A painting of Oceola, "the chief who never gave up," is on a wall in the Muscogee court. American Indian costumes, ancient maps and wampum fill the courtrooms, adding to the sense of tradition. With tradition comes intimacy. Tribal judges pride themselves on running cozy, friendly courts. "No. 1, you're going to be treated much kinder," Moore says when describing what he considers the key difference between tribal courts and those in the state and federal system. "It's more of a people's court. I don't want the Indians who come to court to be afraid." Few tribal courts have electronic security systems. Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe member and attorney Tom Van Norman says a bailiff may be stationed in the South Dakota courthouse if a big case comes in, but high-tech security just is not necessary. It's not necessary in the Ho-Chunk court either. A lone, unarmed bailiff watches over the courtroom, Butterfield says. Plus, the courthouses themselves are much smaller than federal and state courts. Some only have one courtroom. And the rooms themselves look different. The tribe's flag stands next to the American flag -- if the American flag is present at all. "There are tribes that never asked to be Americans, so why should we put a foreign flag in that courtroom?" Shibles says. Tribal emblem seals often are emblazoned on the walls behind the judges' benches. They are in lieu of United States seals. Courtroom lighting is gentler, Shibles says. No glaring, white fluorescent lights. The color tones are soft and adobe. In the Ho-Chunk courtroom, the judge's dais is not elevated. Butterfield is on the same level as the parties, and Flint Knife wants the judicial podium in his courtroom dropped to eye level to foster a sense of community. Currently, his podium is rasied. Other physical differences are more practical than symbolical. Tribal court systems do not have much money, so some courts are run out of trailers. Others are run out of small rooms in office buildings. And having low funds means that paying jurors is expensive. That's why there's no jury box in Flint Knife's courtroom in Toppenish, Wash. His court handles perhaps one jury trial each year. In some tribal courts, lawyers are replaced by lay advocates because professional lawyers are simply too expensive for many American Indians. Lay counsel are drawn from all sorts of professions. Partly because lay advocates are not lawyers and partly because tribal courts aren't as adversarial as state and federal courts, paperwork for each case is thin. In some big city courts, prosecutors roll carts of case files from courtroom to courtroom. Paper is everywhere, and when attorneys present cases, they come armed with thick books and bulging files. "You will never, ever see a case come in here with a cart," Gabourie says. At most, a three-inch binder and a codebook. Flint Knife says he hasn't seen a motion for summary judgment in a year, and he's not sure whether lay advocates know what such a motion is. That cuts paperwork drastically. In Yakama Nation courts, a lay advocate arguing a case will come in with a file folder "with 10 pieces of paper in it, tops," Flint Knife says. Most tribal courts hear a spectrum of cases: custody battles, criminal offenses, civil rights disputes, contract litigation, tort claims, and internal tribal matters, such as election and membership disagreements. When lay advocates, or even lawyers for that matter, present cases in court, sometimes it's not professional judges presiding over cases but wise men chosen from the tribe. Just as the method for selecting judges varies from state to state in the American system -- some judges are elected and others are appointed -- selection varies among American Indian tribes as well. Some judges are appointed by a council of elders. Some are elected by members of the tribe. And when Flint Knife needs a three-member panel of appellate justices, he puts the names of the eight tribal judges in a hat and then draws three of them. Formality, then, is not the No. 1 characteristic or concern of tribal courts. Instead, tribal judges say, the aim is to maintain community, tradition and consensus. "Everybody knows everybody," Flint Knife says. "Courts are really a symbol of the dominant community." |

|

Self-Help Guide to Tribal Courts |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |