|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

March 10, 2001 - Issue 31 |

||

|

|

||

|

A Return of the Natives |

||

|

by Michelle Nijhuis for High Country News |

||

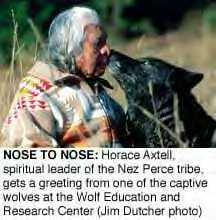

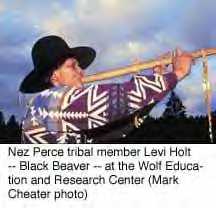

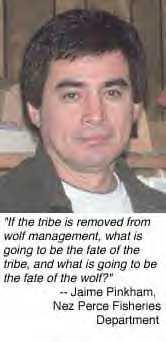

The Nez Perce tribe brings wolves back to the Idaho wilderness -- and reinvents its political

future LEWISTON, Idaho - When Horace Axtell was a boy in the 1920s and '30s, his grandmother would take him on fishing and berry-gathering trips in the Idaho mountains. Like most Nez Perce, they would often work in the forest for two or three weeks at a time. It was on one of those long trips that he heard a wolf howl. "My grandmother was hard of hearing, but she heard it, too," he says. "She explained to me what kind of animal that was, how much it meant to our people in the past and the importance of its being alive." Years later, he took a hunting trip with a friend to the Selway River in central Idaho. "My friend said, 'Hey, look at that big dog!' " he remembers with a chuckle. "I said, 'No, I'm sure that's a wolf.' And it was. I got to see one, with my own eyes." He didn't see another wolf for decades, as ranchers and federal hunters nearly exterminated the gray wolf in the West. In 1974, the wolf landed on the federal endangered species list. Axtell, 76, lives with his wife in a small house on the edge of this placid timber town, 15 miles from the Nez Perce Reservation where he grew up. He's been a soldier, a convict, and an edgerman at the local Potlatch mill. He's now an elder of his tribe, a leader of the traditional Seven Drum religion, a teacher, and an author. He's also an expert swing dancer. And he has lived to see his tribe bring wolves back to Idaho. In 1995, after the state Legislature barred the Idaho Fish and Game Department from cooperating with the federal wolf recovery program, the Nez Perce went to the federal government and volunteered to take the place of the state. The program has since become one of the most successful wildlife recovery efforts ever. The wolves are multiplying with gusto - almost 200 are roaming free in the state - and the population may soon reach the goals set by the feds. Thanks to the state legislators' stubbornness, the Nez Perce are the first and only tribe to oversee the statewide recovery of an endangered species. The tribal wildlife department works side-by-side with the federal government, tracking wolves in the vast wilderness lands that once belonged to the tribe. It's a deliciously ironic opportunity, and the tribe is making the most of it. The wolf program is now just one of many Nez Perce projects on and off the reservation, all aimed at strengthening tribal sovereignty and recovering the lands, livelihood and culture stolen during U.S. expansion. Like wolves released from their cages, the Nez Perce are energetically turning the tables on their own bitter history.  The Nez Perce and the gray wolf have a lot in common. Both were chased from their homes and pushed to the edge of annihilation by Westward expansion. Both still suffer the prejudice of the dominant culture. And both have managed to survive. "When this new way of life came across the frontier, (settlers) wanted to tame the so-called wilderness," says Jaime Pinkham, a longtime tribal council member who now heads the tribal fisheries department. "The way of doing that was to get rid of all the obstacles and the threats to their way of life, and two of those obstacles happened to be wolves and Indian people." For the first white explorers, the Nez Perce were lifesavers, not obstacles. The tribe fed and sheltered Lewis and Clark in the fall of 1805 and the spring of 1806, and the captains recorded glowing descriptions of the Nez Perce. Fifty years later, the land-hungry U.S. government confined the tribe to 7 million acres, squeezing the territory down to just 760,000 acres in central Idaho after gold was discovered in the region. The charismatic Nez Perce leader Chief Joseph resisted the injustice, holding out with several hundred followers in the Wallowa Mountains of Oregon. The U.S. Army soon drove them out of the tribal homeland, and in 1877, Joseph led his group of several hundred men, women and children on a 1,200-mile running fight toward the Canadian border. The Nez Perce almost bested their pursuers, beating them in several battles during the dramatic chase through northwestern Wyoming and Montana. But in Bear Paw, Mont., just south of safety, Joseph and his surviving followers were defeated, captured and eventually exiled to reservations. Despite years of trying, Joseph was never permitted to return to live in the Wallowas. Joseph's legendary heroism is a talisman of sorts for many Nez Perce. His face is on the tribal seal, his picture hangs prominently in tribal council chambers in Lapwai, and the story of his defiance has helped to sustain the tribe through later losses. About two-thirds of the 3,400 members of the Nez Perce tribe now live on their reservation in central Idaho or in nearby Lewiston. The rolling, open reservation land straddles the eastern edge of the fertile Palouse farm country, and it cradles the last stretch of the Clearwater River. It takes hours to navigate the crooked two-lane highway that links Lapwai and Culdesac, Winchester and Craigmont, and the dead-end roads in between. This far-reaching reservation is an illusion. Though the Nez Perce have managed to keep some hunting and fishing rights on 13 million acres in Idaho, Oregon and Washington, the tribe and individual Indians own only about 75,000 acres. The rest drained out when the already-diminished 760,000-acre reservation was opened to homesteading (HCN, 8/3/98: Tribes reclaim stolen lands). Even the tribe's legal jurisdiction on the reservation is challenged by non-Indians living within its boundaries, and that challenge is often infected with a resistant strain of racism. The decline of wildlife, including wolves, has been a further loss for the tribe, since treaty hunting rights are meaningless if there's nothing to hunt. The tribal wildlife program has always tried to offset that political loss. Keith Lawrence, who has headed the program since its start in 1982, remembers asking the tribal council for direction during his first few months on the job. "They just said, 'We don't want to be on the sidelines. If it's happening within treaty territory, we want to be involved.' " The tribe has also suffered from a spiritual loss, says Levi Holt, a former tribal council member and current staffer for the Wolf Education and Research Center on the reservation. Though the wolf isn't as central to Nez Perce culture as the salmon, wolves symbolize wisdom, strength and family loyalty in tribal legend. "Gray wolf, salmon, deer, eagle, whatever the species may be, they have a place and a purpose," adds Holt. "When humans remove or destroy that link, that connection, we lose. And everyone loses, of course, in the world and in this region, but the Nez Perce lose a bit more of their culture, of their spirituality, and most certainly of their treaty rights."  So the Nez Perce were paying close attention in 1991, when Congress directed the Fish and Wildlife Service to develop a recovery strategy for wolves in the Northern Rockies. Two years later, after receiving more than 160,000 comments from across the United States and abroad, the agency published a final environmental impact statement (HCN, 7/26/93: Wolf plan brings praise and howls). The document named three recovery areas: northwest Montana, where wolves would be allowed to naturally recolonize; greater Yellowstone, where wolves would be held in pens and then released; and central Idaho, where wolves would be released directly into the wilderness. Opposition in Idaho was fierce. Potlatch Timber Corp., the economic linchpin for the working-class city of Lewiston, opposed the program because it feared it would be shut out of public forests. Idaho ranchers, facing low meat prices, thought wolf predation would mean the end of their businesses. Hunters hated the idea of sharing their prey with wolves, and state officials, from Democratic Gov. Cecil Andrus on down, spoke vehemently against wolf recovery. But when the Legislature appointed a seven-member Wolf Oversight Committee to recommend a state strategy, the committee voted 5-2 to cooperate with the federal government. "I compared it to a football game," says Don Clower, a hunter and retired U.S. Postal Service employee who was a member of the committee at the time. "If we weren't on the field, we had no chance of scoring." The Legislature disregarded the recommendation, and in 1995 it overwhelmingly voted to prohibit Idaho Fish and Game from having anything to do with wolf recovery. "Nobody wanted to capitulate to the federal government," says Clower. After the state resolution, Jaime Pinkham says wryly, "some people thought that this nonsense about bringing wolves back to Idaho was just going to go away." It didn't. The federal plan had to go forward, with or without the state, so Fish and Wildlife Service staffers started looking for someone else to take on the state's local management role. Charles Hayes, then the chairman of the Nez Perce, thought the tribe was ready for the job. Hayes, who died in 1996, had helped to develop the federal wolf recovery plan, and he thought the program was a rare chance to work as an equal partner with the federal government. He was very convincing, remembers Pinkham. "The tribes have always been trying to elevate their status when it comes to natural resource management, so when the Fish and Wildlife Service was looking for a new partner, we were right there. "We brought forward the idea: Let the tribe do it." Levi Holt, who was on the tribal council at the time, says it was a scary decision for the Nez Perce. Wolf recovery was controversial and high-profile, federal funding was tight, and there was no guarantee of success. Some feared the tribe risked a backlash from the state government, and many worried that failure could have repercussions for wildlife restoration projects throughout Indian Country. "Everyone felt it was a beautiful dream," says Holt. "Whether or not there was a reality at the end of the dream was something we were a bit concerned with. But it was something that we could not walk away from, we could not turn our backs on, because that's been the spirit of Nez Perce from the beginning."  The Nez Perce are now five years into the recovery program, and they've discovered that wolf work always includes a dose of uncertainty. From the cramped back seat of one of the monitoring planes used by the wolf program, the Idaho wilderness is a crumpled landscape of snow-covered peaks and ravines, and only the occasional ranch or road is visible from the air. Curt Mack, the head of the wolf recovery program for the tribe, gestures at the deep gorge of the Selway River and describes a mystery. "We've released wolves in this area, but they've never stayed," he says, his voice crackling through his microphone. He speculates that a natural pack of wolves has claimed the territory, but staff biologists have never seen it. Mack has been doing these surveys since early 1995, when the Nez Perce wildlife department became responsible for managing wolves in every corner of this panoramic landscape. The Fish and Wildlife Service had just released 15 wolves from Canada into central Idaho, and a release of 20 wolves was planned for the following year. So tribal wildlife program staffers jumped into the game: They wrote a management plan for the wolves. They opened an office in McCall, Idaho, a couple of hours south of the reservation, so that staff could be closer to the main recovery area. They relocated the nonprofit Wolf Education and Research Center from Sun Valley to reservation land in Winchester, so central Idaho residents could get a close-up look at a pack of captive wolves. In 1996, they helped oversee the second wolf release. The early days were tricky. "The relationship between the tribe and the Service didn't happen overnight," says Mack. "It took a lot of nurturing over several years, and for understandable reasons. To take something that is so politically and emotionally charged and hand it over to an unknown entity - it was a big step for the Service." The federal agency gradually gained confidence in the tribe. Now, with a $300,000 annual budget from the Fish and Wildlife Service, two full-time biologists and their four- to six-person seasonal staff monitor all of the radio-collared wolves, keep tabs on pack behavior and reproduction, and relocate wolves that attack cattle or sheep. As local ambassadors for the wolves, they also meet with ranchers and others in the area to calm fears and build support. "They've been a godsend," says Ed Bangs, who runs the gray wolf recovery program for the Fish and Wildlife Service. Since tribal wildlife department staffers live in the recovery area, he explains, they can respond quickly to problems and win the trust of locals. "I don't think the program would have been as successful without them," he says. The Fish and Wildlife Service found it easier to relax when wolf numbers boomed beyond all expectations. Though the agency had planned for as many as five releases in Idaho, two were enough. Surveys in 2000 estimate 191 wolves, with 18 packs producing 16 litters of pups this past season. "Idaho has such a large geographic area of basically undeveloped country," says Mack. "That's been the key. It's nothing to do with us, it's all the wolves." The recovery area is so gigantic - 15 million acres - that biologists cover hundreds of miles by foot every summer, hoping to spot new pups or pairings. Throughout the year, staffers use small airplanes to search for the 49 wolves which are wearing radiotransmitter collars. And guesswork is always required. In country this big, no one can know where all the wolves are all the time. Wolf recovery is chancy in other ways. The pilot of the monitoring plane, Mike Dorris, has worked with the wolf program for years, and has a gallows sense of humor that must come with a flight license. "When do we have to worry about ice on the wings?" Mack asks casually, as the clouds start to thicken. "Now," deadpans Dorris.  The wolves may be unknowable, but they're much easier to please than their human neighbors, some

of whom are still furious about the wolf program. "Wolves are going to do fine, all on their own," says

Mack. "Ultimately, this is not a biological problem. It's a social problem." The wolves may be unknowable, but they're much easier to please than their human neighbors, some

of whom are still furious about the wolf program. "Wolves are going to do fine, all on their own," says

Mack. "Ultimately, this is not a biological problem. It's a social problem."Mack is not a tribal member, but he has become the most visible representative of the wolf program in Idaho, and he often drives down the winding road from McCall to Boise to meet with state officials. Over the years, he's taken a lot of political heat, but he says there are a few signs of change. A case in point is Margaret Soulen-Hinson, who comes from a long line of Idaho sheep ranchers. She runs about 16,000 ewes and lambs on public and private land each summer, and typically loses over 1,000 lambs to coyotes and other predators every year. Over the last five years, she's also lost close to 100 to wolves, more animals than any other Idaho rancher. "I'm not wild about the wolves eating my sheep, but the program has worked fairly," she says. "The first year was probably the most frightening, when we lost 30 head and didn't know how things were going to work." The tribal wildlife department has a bag of tricks to help ranchers drive off wolves. They organize volunteers to try to chase off the wolves, and set out speakers that blast frightening noises. If these methods don't work, and if relocation fails, the federal Wildlife Services agency can be called in to kill wolves, or ranchers can get "take" permits from the Fish and Wildlife Service. Only one reintroduced wolf has been legally killed in Idaho, and 12 have been killed illegally. The attention from tribal biologists calmed Soulen-Hinson's fears. "We're working together on this," she says. The tribe has formed good relationships with many ranchers, she adds. "When the tribe took on the wolf program, I really felt it was better than if it had been (Idaho) Fish and Game. Fish and Game has traditionally been focused on sportsmen, and they have not always worked that well with landowners. The tribe was able to deal with a lot cleaner slate." The national environmental group Defenders of Wildlife has also provided some help for ranchers: The group has bought extra sheepdogs for ranchers, and pays for sheep and cows that are lost to documented wolf kills. Though Soulen-Hinson says evidence of kills is often hard to find ("They leave a pretty clean plate,") the money has been welcome, and she thinks her extra dogs may have kept the wolves away last year. Jack Ellis, a rancher in Salmon, Idaho, says the compensation has softened his attitude toward the recovery program. "When we sell a lamb or a calf across the scales, we get such-and-such per pound for them," he says. "Now we know we're going to sell some of these calves through wolves. If we can sell them that way, fine." Time may be the best antidote for the anger about wolves, says Suzanne Laverty, the northwest representative for Defenders of Wildlife. "We're starting to see people who are more towards the middle," she says. "We've lived with wolves for a while now, and you can't replace that personal experience." Changing attitudes were on display last Halloween night, when Laverty went to a federal wolf hearing in Boise. She dressed in a red cape and boots, as Little Red Riding Hood, and even the ranchers in the audience allowed themselves a few laughs.  This sounds like the beginning of a happy ending. The Nez Perce have won admiration, however grudging, from their adversaries. The wolves are thriving, kids in tribal Head Start are learning the Nez Perce word for wolf, and wolves are even finding their way back into traditional tribal ceremonies. But this period of peace may be over all too soon. Wolf numbers are continuing to rise, and some animals are wandering widely in search of new territory. Three wolves have traveled into eastern Oregon, and there were unconfirmed sightings on the outskirts of Boise last fall. "My ancestors would be shocked," says Brad Little, a sheep rancher in Emmett, Idaho, and an HCN board member, whose guard dogs have been attacked by wolves. "We have way more cougar, way more bear, way more coyotes than we used to. If the wolves kill our guard dogs, we're wide open to all these other predators." "The consensus among cattle ranchers is that we can live with wolves if we can control the number of wolves there are," says Jack Ellis. "If there are between 150 and 200 wolves in central Idaho, we can probably live with it." Soulen-Hinson says much the same thing, arguing for a "threshold" on the wolf population. There's no federal threshold, but there's one major benchmark for the growing population: Wolves will be officially recovered in Idaho when there are 10 breeding pairs in the state. Because of the narrow federal definition of a breeding pair, the Idaho population hasn't quite hit that magic number. When it does, the Fish and Wildlife Service will start the long process of taking the gray wolf off the endangered species list. Since federal law gives states the responsibility for all non-endangered wildlife, Idaho will then take charge of its wolf population. The federal agency has already proposed to downlist some populations of wolves from endangered to threatened. Though the proposal wouldn't affect the reintroduced populations in Idaho and Yellowstone, and full delisting of all gray wolves isn't expected to happen for three to five years, the state is planning ahead. The Wolf Oversight Committee completed a draft plan for state wolf management last summer. The committee went through about 15 revisions before it could even agree on a draft, says committee member Jim Peek, and the plan remains internally controversial. As it stands, the plan would give primary control of the wolves to the state, keeping wolf numbers at the bare-minimum 10 breeding pairs required by the federal government. Limited hunting would be used to control wolf numbers and earn money for the program. The tribe would be responsible for monitoring the wolves, but it would have little or no say in hunting regulations or other aspects of wolf management. "There wasn't a whole lot of support for making the tribe an equal partner," says Peek, a retired wildlife biology professor from the University of Idaho. Though he'd like to see the committee strengthen the tribe's role, he emphasizes that the state needs to take charge of the program. "I can live with what we came up with," he says of the draft plan. "We need to recognize the experience of tribal biologists, but we need the wolf to be considered an integral part of the state's wildlife resource." If the state agency is responsible for the wolves, he says, it will be forced to "sharpen up" its management of deer, elk and other prey species. Rancher Brad Little has a harsher take on the tribe's role. "The state ought to have a dialogue with the tribe, but the Fish and Wildlife Service is not going to get out of the picture, and Wildlife Services is not going to get out of the picture," he says. "The tribe is kind of like a third wheel." "If the tribe is removed from wolf management, what is going to be the fate of the tribe, and what is going to be the fate of the wolf?" asks Jaime Pinkham. "This (state) plan is not for the wolf, and it's not for the community that assured its return." The wolf program hasn't been a moneymaker for the tribe. It hasn't created a lot of jobs for tribal members, since most of the program staffers are non-Indians. It has, though, forged a successful partnership between the tribe and the federal government, and the tribe isn't going to let that be forgotten. Like most tribes, the Nez Perce sees itself as a sovereign nation, and tribal sovereignty has been backed up by most recent federal court decisions and legislation. Sovereignty is also supported by the nation-to-nation treaties most tribes signed with the federal government, even though those treaties have been repeatedly violated over the last century and a half. But sovereignty is a notoriously difficult concept. Tribes aren't exactly like foreign countries, since tribal members are U.S. citizens and vote in federal elections. Many tribes say they're more like separate states, with self-governing powers and a government-to-government relationship with Washington, D.C. The states themselves often challenge this comparison, and they've fought for jurisdiction over tribal casinos and other development projects. When the state of Idaho gave up its role in wolf management, it unwittingly strengthened the sovereignty of the Nez Perce, altering the complicated relationships between state, tribal and federal governments. It's given the tribe political confidence - and a precedent to build on. Some state officials would like the tribe to retreat back within reservation boundaries when the wolves are recovered, but it may not be that simple. Though Nez Perce officials know that the political geometry will change with delisting, they want to maintain a long-term role in the program, at least on the 13 million acres where the tribe has treaty hunting rights. And some argue that the program could use continued help from the tribe. Carter Niemeyer of the Fish and Wildlife Service has worked on wolves for the last 15 years, and he points out that there's plenty of work to go around. "It's seven days a week, 24 hours a day," he says. Even a few state legislators say the Nez Perce should be a permanent part of the program. Republican state Sen. Laird Noh, a sheep rancher in southern Idaho, says the state should contract with the Nez Perce to continue managing the wolves after delisting. "The tribe has done an exemplary job," he says. "There's a great deal of accumulated knowledge that shouldn't be lost in the transition." Nez Perce officials have asked Republican Gov. Dirk Kempthorne for a voice in the state planning process, but the tribe isn't waiting around to see how the controversy plays out. Even if the Nez Perce have to step out of wolf management altogether, the state of Idaho won't have seen the last of them. They're hard at work writing their own happy ending. The tribe has continued to work on salmon recovery, employing as many as 200 people each year to work at tribal hatcheries and on restoring habitat. It strongly backs breaching the dams on the Snake River, and has joined with three other tribes to form the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. Grizzly bears are likely to be reintroduced to the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness on the Montana-Idaho border within the next five years, and the tribe wants a seat on the planning team. Four years ago, the Nez Perce also worked with the Trust for Public Land to buy back 10,300 acres of the Wallowa homeland, which is now managed as a wildlife preserve. Since then, another 5,100 acres have been added to the preserve. It adds up to a significant chunk of territory, one with huge symbolic weight. The wolf and the Nez Perce are still following parallel paths, says Pinkham. "Now it's a more optimistic journey," he says. "You see the tribal status elevated as a natural resource manager, and you see the return of the wolves to Idaho. Both of us are regaining our rightful place on the landscape." Tribal elder Horace Axtell agrees. In 1996, he and other tribal elders welcomed the second batch of wolves back to Idaho with a blessing. "I sang some of my spiritual songs for them, and I looked in at one or two of them and told them in my language, 'I'm glad you're coming back,' " he says, settling into an armchair in his Lewiston home. "And they just looked at me like they understood me. That was a good feeling. "There's a good coming along," he says. "It makes me feel a little more comfortable. We've got our foot in the door." Michelle Nijhuis is an HCN associate editor. This article was supported by The San Diego Foundation/The Engle Fund at the recommendation of David Engle. You can contact ... Nez Perce Wolf Recovery Program, 208/634-1061; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wolf Recovery Program, 406/449-5225 ext. 204; Idaho Fish and Game, 208/334-2920; Suzanne Laverty, Northwest representative, Defenders of Wildlife, 208/424-9385; Idaho Cattle Association, 208/343-1615. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

|

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |