|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

February 24, 2001 - Issue 30 |

||

|

|

||

|

A Ray of Hope Cheers Indian School |

||

|

by Henry J. Cordes Omaha World Staff Writer |

||

|

"Those going against the wind" |

Macy, Neb.

- Classes have been out for almost two hours at Omaha Nation Public School on the Omaha Indian reservation, but

the halls are still alive with learning. Macy, Neb.

- Classes have been out for almost two hours at Omaha Nation Public School on the Omaha Indian reservation, but

the halls are still alive with learning.In one room, two fourth-graders work on cursive writing, carefully crafting "S" after "S." Down the hall, a half-dozen students read stories and then rewrite them, coming up with creative endings of their own. Next door, students engage in a fast-paced math game, racing to be first to shout out the correct answer. The students are part of a unique after-school program of tutoring, enrichment and cultural activities aimed at boosting achievement in the school. It's called Project Wash-kon, a name, in the Omaha tribe's traditional language, that represents a powerful statement of encouragement. "It's like your mother saying to you, in an impassioned way, 'I want you to succeed in life,'" said tribal member Ed Webster. Wash-kon, school officials say, is what they want for all children on the Omaha reservation. Wash-kon is also something that, for generations, not nearly enough Omaha Indian children have achieved. It has been a year since The World-Herald visited Omaha Nation in "Broken Promise," a series that detailed the tragedy of American Indian education in Nebraska and the nation. In Omaha Nation, on the Omaha tribe's reservation 60 miles north of Omaha, truancy is epidemic. Students on average miss one day of school a week. Standardized test scores are among the lowest of any school in the nation. At least three out of every four students drop out. Things are not a lot better in the three other Nebraska public school districts on Indian reservations - or in most reservation schools nationally. Indian students in urban schools often fare even worse. But even though the dismal figures behind the problems in Indian education have not changed much in a year - and in some cases have even gotten worse - there is more reason for hope in Nebraska's reservation schools. The State of Nebraska is recognizing the problem. The Legislature on Tuesday will begin considering a bill pushed by the state commissioner of education that would provide an additional $6 million in state aid to the schools. And people on the reservations and in the schools have not been sitting back and waiting for help. They are seeking to get parents more involved, trying to find new ways to get children to come to school and stay, focusing on improving reading skills and setting high standards for students. "We're not waiting around," said Cheryl Kinnaman, a teacher in Walthill, an Omaha reservation school that is a year into a schoolwide improvement plan. "We're real hopeful for the future." The new after-school program, funded by a U.S. Education Department grant that will also make summer school available beginning this year, is just one way that Omaha Nation is working to move ahead. The school has significantly boosted its pay scale for teachers - its starting salary of about $25,000 now exceeds the state average - in an effort to stop high turnover that in some past years has cost the school half its staff. And after years of seeing nearly all of their teachers drive to homes off the reservation after school each day, students may also soon see members of their own tribe in the classroom. Omaha Nation and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln last year established a teacher training program to help tribal members get college degrees and teaching certificates. There are 17 enrolled, including three who are expected to receive degrees in May. For someone who grew up on the reservation without seeing an Indian teacher, Libby Webster said the thought of becoming one seemed unattainable. To her, it would be like suggesting she become a doctor. But she's now student-teaching in the school, with ultimate hopes for a classroom of her own. "When I see that lightbulb moment in their faces, it's real gratifying to me," she said. The tribal teachers make a difference just walking down the hall, school officials say, serving as role models and giving kids and their parents a stronger connection to the school. "If the kids see me at the store or around town, they're real excited," said Delberta Lyons, who also expects to graduate in May. Omaha Nation also is seeing encouraging results from a reading program that breaks all elementary students, based on ability, into small groups without regard to grade level. At the start of school two years ago, only 9 percent of elementary students were reading at their own grade level. Today it's 43 percent. Second-grader Khiry Webster is among those turned on to reading. "You learn a lot," he said, "and it's fun." Despite those gains, Omaha Nation officials have no illusions about how far they still have to go. Truancy continues to be a daily headache and challenge. The absentee rate increased from 17 percent to 20 percent last year, even as the school increased its staff of truant officers from one to three. Truant officers, administrators and teachers constantly work the halls, the grounds and the reservation urging students to get to class. And after graduating 11 students last year, only five are expected to walk away with diplomas this spring. When this year's seniors were in the sixth grade six years ago, 26 were in the class. Parish Sheridan, one of this year's seniors, said drugs and alcohol took a big toll on his class. "Me and my friends have stayed away from that," he said. "But there's a lot of it around here." Teachers and administrators at Omaha Nation say there's no doubt their students face personal challenges beyond those of any school in the state. Nearly two-thirds of the families on the reservation live below the poverty line. Schools officials tell stories of the dysfunction they see daily: youths who wander the streets at all hours of the night, students who flee beatings from binge-drinking parents, kids with no role models who see no value in education, and community drug abuse so pervasive that some students don't even know it's illegal. To help students face those challenges, the school for years has sought to establish a support services center, putting a mental health therapist, a drug and alcohol counselor, a nurse, a social worker and a juvenile probation officer right in the school. The school hoped to land a state lottery grant to fund the proposal last year, said Dave Friedli, Omaha Nation's high school principal, but it was rejected as being not closely enough related to education. "Those people," he said, "don't understand us at all. If you do not deal with those issues, kids are not ready to learn." But state education officials are awakening to the plight of children in reservation schools. State Education Commissioner Doug Christensen said he is encouraged by the renewed sense of commitment to education in reservation communities. But he is also convinced the state will need to partner with the schools - and put more state money into them - if the bleak statistics are ever to be reversed. Christensen said the state has a moral and legal obligation to act. Though situated on reservations, the schools are legally no different from public schools in other Nebraska communities. The state has an obligation under state law to make sure all public school districts provide an adequate educational opportunity. Clearly, he said, the reservation schools are not. For more than 25 years, he said, the state was aware of the problems but did little to help. There was an attitude that it wasn't the state's problem. "We would never have let something like this happen in Minden," he said during a visit to Omaha Nation last week, referring to a public school district near Kearney. "But we let it happen here." Christensen is proposing direct aid to reservation schools with a bill that would provide more state dollars to schools with at least 35 percent of their students living in poverty. Legislative Bill 478 would tweak the current state aid formula to redirect to the "extreme poverty" districts about $15 million of the $650 million in school aid dollars the state distributes annually. About $6 million of those dollars would go to the four reservation districts. Christensen said current state aid should already be providing for most of the basic academic needs in the reservation schools. The intent of the new dollars is to help provide students the support to succeed, with programs such as drug education and counseling, tutoring, or parent education. Schools would have to report to the state on their plans for the funds, be accountable for how they're spent and report their results. Along with the support center, Friedli said, Omaha Nation has a long list of needs it would seek to meet with more funds. The school has explored the cost of getting basic telephone service into the home of every student. It's estimated that only one-third of families in Macy have phones, cutting a vital link that could help get parents involved and aid in tracking truants. Friedli said more money also could help the school reduce class sizes, establish an alternative education program for dropouts and other at-risk students and improve its well-worn, badly overcrowded building. Unlike other schools, Omaha Nation cannot pass a bond issue to raise money for building improvements. Most land on Indian reservations is held in trust by the federal government and exempt from taxes. For years, the reservation schools have struggled to cobble together enough money to repair and improve facilities. Friedli said he's convinced that with the right encouragement and support, most kids on the reservation can rise above their circumstances and make it. He and Christensen agree that it will take the state, the schools, the tribes and the reservation communities all working together to break the cycle. "It will take a generation of effort to solve this problem," Christensen said. "If we don't do something, we'll lose another generation." |

|

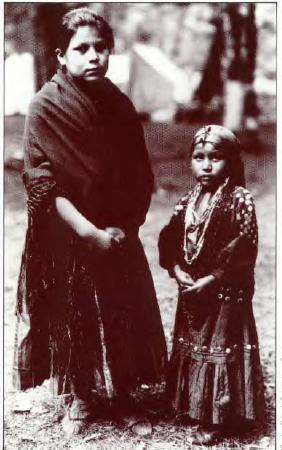

Omaha Tribe Buffalo Hunt |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

|

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |