|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

February 24, 2001 - Issue 30 |

||

|

|

||

|

A Perfect Fit |

||

|

by Dan Webster Staff Writer The Spokesman Review |

||

Michelle Hall

embraces her Colville Indian roots while doing promotions for Native American filmmakers and musicians. Michelle Hall

embraces her Colville Indian roots while doing promotions for Native American filmmakers and musicians.Michelle Hall jumped at the chance to promote the documentary, "Alcatraz Is Not an Island," at the Sundance Film Festival. The distance between Inchelium, Wash., and Park City, Utah, is a lot farther than the mere miles that separate them. No one knows that better than Michelle Hall. For Hall, who grew up on the Colville Indian Reservation, closing that distance has involved attitude. It has involved perception. In the end, it has involved spirit. As her mentor, film producer Millie Ketcheshawno, told her, "Keep your spirit because you're going to get knocked down, and you need to stay true to what you believe. And always remember what it is you want to achieve."  These days, Hall lives and works in San Francisco, where she runs her own public relations business.

Last month she was in Park City, site of the prestigious Sundance Film Festival. Bumping elbows with the best of

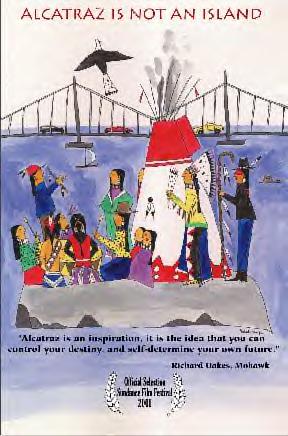

the country's alternative filmmakers, she was helping publicize the documentary "Alcatraz Is Not an Island,"

a 70-minute film about the 1969-71 Indian occupation of the former federal penitentiary. These days, Hall lives and works in San Francisco, where she runs her own public relations business.

Last month she was in Park City, site of the prestigious Sundance Film Festival. Bumping elbows with the best of

the country's alternative filmmakers, she was helping publicize the documentary "Alcatraz Is Not an Island,"

a 70-minute film about the 1969-71 Indian occupation of the former federal penitentiary.But Hall does know what it's like to get knocked down. Born 31 years ago in Hemet, Calif., Hall was just three weeks old when her parents moved back to the Inland Northwest. The next several years were, in Hall's words, a "turbulent" time. Most of that turbulence involved her parents who, she says, "loved each other, but they were just two Indian people who couldn't be together." When they split up, Hall and her younger sister were left primarily in her grandmother's care. "My life was my grandmother," Hall says. "She was it for me. Through her I learned unconditional love." Nevertheless, Hall remembers her adolescence seeming like an ongoing trek between schools in Inchelium, Wash., and Coulee Dam. By her senior year, she was attending Coulee Dam's Lake Roosevelt High School. Living in her own apartment, working and playing three sports, she studied just enough to get by. When she graduated in 1987, she didn't even consider college. "Growing up on the reservation," Hall says, "I didn't really think that college was an option for me." Instead, she moved to Spokane, where she spent two years working as a paralegal with the late Carl Maxey's law firm. Married at 19 and divorced 18 months later, she decided to leave the Northwest. "Seattle wasn't far enough," she says, "and Oregon was too much like Washington. So I decided to move to the Bay Area." She knew no one there. But with her experience as a paralegal, she got a job right away. She still harbored deep feelings of self-doubt, but gradually she began to glean a sense of her abilities. "Never in a million years did I think I could leave home or that I would amount to anything," Hall says. "I had these dreams, but I just didn't think that I would ever do anything that would matter. But that whole experience gave me confidence." As a paralegal, she worked on a number of major cases -- the estate of the late concert promoter Bill Graham, for example, and the winery ownership of filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola. But she eventually soured on the law. So in 1995, she took a job in corporate communications at a Bay Area biotechnology company specializing in gene research. She met regularly with members of the San Francisco media, and ultimately she began working for the advertising agency that handled the corporation's account. Soon she was learning about ecology and pharmaceutical products, about neurology and medicines designed to treat such afflictions as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease and epilepsy. She learned so much, and gained so much confidence in the process, that she ended up going free-lance. "Essentially, I worked out of my house," she says. "Whatever the job entailed, I brought on other free-lancers -- designers, writers, artists -- and we got the job done." Just eight years after leaving Spokane, Hall had succeeded beyond her wildest dreams. The time was ripe for her to grow in a different direction. She had, after all, taken college courses: paralegal courses at Spokane Falls Community College, then general courses at San Mateo Junior College. She eventually attended the University of California-Berkeley in 1994-95. She left without getting a degree but not before realizing something about herself. "I got tired of people trying to get me to join their causes," she says. "I didn't know what my causes were or even if I had any causes." A cause is exactly what she found when, tired of working with medical research companies, she started looking for a new challenge. While working with the American Indian Film Institute, she attended the group's 1999 film festival. "The experience with the festival that year was so enlightening and so empowering," she says. "My heart was feeling so connected, which it hadn't been all those years that I had been in the Bay Area. Emotionally, I began feeling all these repressed emotions." Being around other Indian people was what did it. "They would say, act and do mannerisms that people back home did," Hall says. "These people were geographically nowhere near my people, and yet they were talking about fry bread and macaroni soup and saying `enit." One person that she met was film producer Ketcheshawno. It was through her that Hall got involved with "Alcatraz Is Not an Island." And it is for the sake of Ketcheshawno, who died in December, that she remains working on the film for free. She'll continue to do so as it makes the rounds of film festivals in search of a distributor. "I had to get the word out," Hall says. "Millie worked too hard to get the film to that point, and getting to Sundance was the icing on the cake for her. I just couldn't let it sit." Nor does she intend to sit on her own career. In a few weeks, Hall plans on attending the Grammy Awards with another of her clients, Joanne Shenandoah, a nominee for Best Native American Music Album. She's working with Arizona musician Keith Secola, and she's looking for other native people and issues to promote. Hall still pauses now and then to marvel at her life and the spirit that propels it. "People tend to migrate toward me now," she says, "and I have to believe that it's because I'm true to my heart." |

|

Alcatraz is Not an Island |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

|

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |