|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

January 13, 2001 - Issue 27 |

||

|

|

||

|

Keeping in Touch |

||

|

Radio play-by-play helps Navajos stay in the game |

||

|

By Scott Howard-Cooper Bee Staff Writer |

||

|

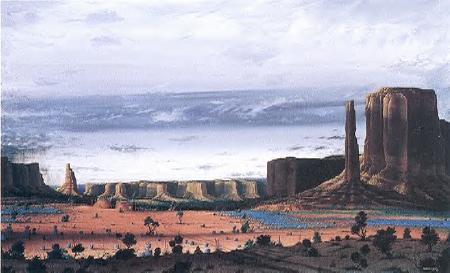

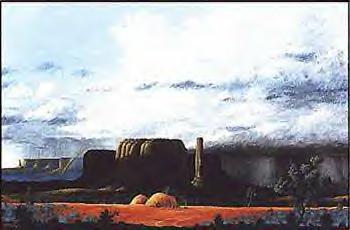

artwork by Clifford Brycelea |

||

WINDOW

ROCK, Ariz. -- The drive is 70 miles through the Navajo Nation, as dogs and men on horseback herd sheep across

the road and the sun strains its final light of the clear, crisp day on the red mesas and the journey goes from

state highway to the slivers of the Indian Route. It's two lanes most of the way, with as many animals spotted

as cars and even fewer signs of human settlement. WINDOW

ROCK, Ariz. -- The drive is 70 miles through the Navajo Nation, as dogs and men on horseback herd sheep across

the road and the sun strains its final light of the clear, crisp day on the red mesas and the journey goes from

state highway to the slivers of the Indian Route. It's two lanes most of the way, with as many animals spotted

as cars and even fewer signs of human settlement.A dead end, one final turn, three more miles, and the little house without a phone is on the left, on the outskirts of White Cone. There is no address, only a hand-drawn map that must be trusted, an easy-enough concession: There is no other life on the left. Up a slight incline, through the gate, along the 50-foot driveway of gravel and dirt and ruts to the front door. Outside, the temperature is in the low 30s, and the forever sky of nighttime has all but taken over, interrupted by a spotting of stars and a few lights from two homes 100 yards to the north. Inside, Henry and Rosebelle Dickson have finished dinner. Their friend, L.A. (for Laura Ann) Williams, is ready in Phoenix, after the four-hour drive to the southwest from Window Rock. They will listen to her on the radio on the end table in the front room, just as some will sit in their cars in the darkness to hear and others will tune into KTNN on the old hand-held transistors. Rosebelle used to have to do that, before the Dicksons got electricity eight years ago and bought the boombox that plugs into the wall. "Battery after battery," she says, recalling how it used to be. Year after year. KTNN has been doing this since 1993, broadcasting about three Phoenix Suns homes games a month in Navajo and beaming 50,000 watts to the most unique audience in the National Basketball Association, transmitting throughout the 17 million acres of the reservation that covers parts of New Mexico, Arizona and Utah, and even reaching beyond. They have heard from listeners in western Canada on nights when the weather cooperates and consistently from as far north as Oregon and Idaho, all while some professional teams target only an English-speaking audience and the Sacramento Kings this season ended an affiliation with a Spanish-language station. Even on the reservation, it is impossible to gauge exactly how many people are tuning in. This land of 175,000 people, spread over an area the size of West Virginia, is not exactly conducive to listener surveys -- "Not me," said Ernie Manuelito, who used to broadcast the games and is now chief of operations at the station. "I'd get lost, too." And he grew up on the reservation. So vast is the Navajo Nation that the literacy rate goes untracked by its officials. What is known is that, according to the Navajos' Division of Economic Development, the unemployment rate is 45.8 percent, the per capita income is $5,599, and the median monthly cost of a two-bedroom apartment is $300. Small homes don't need to pass a safety inspection before being inhabited, and some barely look able to withstand a strong wind. Rosebelle Dickson's sister, seven miles away, doesn't have electricity, and to get water must load barrels onto the bed of the truck and drive to the store to fill them. Rosebelle's two grandsons go 40 miles each way to the nearest school. Their life would be a surreal existence to almost everyone else in the United States. But the Dicksons, Rosebelle, in her late 60s, and Henry, in his early 70s, have it good in comparison to others on the reservation. They got their first television three months ago, and their small house is a sound structure, unlike most others along the drive that appeared more the papier-mâché variety. This is another cold night in December, but at least there is no snow coming, unlike the dusting 48 hours earlier. The black, wood-burning heater in the Dickson living room, with a coffee can full of water placed on top to keep the air moist and the pipe climbing to the ceiling and beyond to dispatch the smoke, makes it comfortable as the matriarch eases onto the floor. She has wool, taken from the 18 sheep penned about 30 yards from the back door, a heavy brush and a 2-foot-high spinning wheel. Rosebelle is making a saddle blanket. It's a few minutes before 6 p.m., and this is how she likes to listen to the games. The couch is against her back, the boombox at arm's length to her left and already turned on. Elvis is singing "Blue Christmas." The television, a modern set, is 10 feet away, but no one has yet noted that the game is going to be on TNT, so it remains dark. KTNN has an eclectic lineup -- some country music, some traditional Indian music, and some talk in Navajo and English -- so the sudden switch to pro basketball does not seem out of place. This is the second broadcast of the month on The Voice of the Navajo Nation, as AM 660 bills itself, and one of 19 Suns games scheduled for broadcast during the season. The Suns approached the station after seeing the fan support when a local high school team made the state championship 340 miles away in Phoenix. The team likes the pipeline into a market that would otherwise go untapped, and the Navajos love the tunnel to life outside the reservation. "That's the only ties you have to the outside world," Manuelito said. "I think that would make me happy. You have that connection to KTNN and the Phoenix Suns and all the NBA. You don't feel like you're a forgotten Indian in the middle of nowhere." Williams begins in the language of her ancestors. "Good evening, listeners across the Navajo Nation. Thanks for listening on this third day of the week." It's a Wednesday. "A lot of you are coming back from a productive day. It is cold up north, but it is a bit warm here in Phoenix." With that, she is off. As on past nights, there are challenges. Originally, it was convincing many men in the listening audience that a woman was capable of broadcasting sports. More recently, it has been finding the balance between delivering the action in Navajo and English. The station's general manager, Chester Francis, is encouraging her to go more with English and every few minutes summarize in Navajo. Williams, aware of estimates that 30 percent of her listeners rely entirely on the Indian language, doesn't like the idea. She goes heavy on the Navajo and smoothly transitions to English on occasion, and then back again. Her popularity on the reservation has soared through the years because of the broadcasts of basketball, rodeo and football, from the popular high school competitions to the Suns and, at one time, the Arizona Cardinals of the National Football League, but the NBA is problematic. It can move so fast, and Navajo is a language of detailed description, so Williams expends most of her energy staying on top of the action. It's not easy when traveling is explained as, "The player ran when he needed to dribble," and a breakaway is, "He's running really, really fast with the ball, and they're chasing him."  Rosebelle Dickson listens as she works the wool for the saddle blanket, her face stoic throughout.

Only after a visitor points out that the game is also on TNT does one of the grandchildren bound toward the television

and turn it on, but the volume stays down. Marv Albert and Mike Fratello don't stand a chance against L.A. Williams

here. Rosebelle Dickson listens as she works the wool for the saddle blanket, her face stoic throughout.

Only after a visitor points out that the game is also on TNT does one of the grandchildren bound toward the television

and turn it on, but the volume stays down. Marv Albert and Mike Fratello don't stand a chance against L.A. Williams

here."The television signal does not reach most parts of the reservation, especially the northeastern Arizona side," said Deenise Becenti, the KTNN news director. "Being able to pick up a color television signal is a luxury, so most people only have the radio as their companion at night. "A lot of the homes don't have electricity here. They pick the games up with battery-operated radios. Your closest neighbor might be five or 10 miles away. And the roads are primarily dirt roads, so when people get home, they stay home. It's not like they can just go down the street to get a gallon of milk. It's not that simple. So radio for a lot of people is the only source of news, information and entertainment." Batteries and a transistor can be everything. There's a good chance they're listening on the overnight shift at the coal mine on the fringe of Window Rock -- the home of KTNN and the capital of the Navajo Nation -- and at other jobs. Because kids learn the native language in addition to English, families can listen together late into the night. Henry Dickson sits quietly off to the side, but the three grandchildren are nearby from tipoff as Rosebelle brushes and spins the wool. "They're listening and learning Navajo," she will say later. A proud heritage gets passed down, the generation gap shrinks. Behind-the-back dribbles are a conduit. "It's nice to talk English and Navajo -- both of them," Rosebelle adds. "So they won't forget our language. Our old, old grandmother, she would say: 'You should talk Navajo. Don't forget the language.' Just like what I was doing with carding the wool. 'Don't stop the carding.' "That's what we tell our grandchildren now. 'Chop the wood. Build the fires. Herd the sheep.' Everything that our grandmothers used to tell us." A few feet away, the chopped wood inside the heater is a cushion from the biting air outside. Williams stops her play-by-play midway through the second quarter, with the game still going on, and announces in English they are cutting to a live remote to promote the Christmas sales at the Window Rock Shopping Center. No one in the house takes notice of the game's interruption. The Suns win the game. The next morning, Williams drives the four hours back to Window Rock, just inside the Arizona-New Mexico border, a journey to the northeast that stops about 75 miles south of the Four Corners intersection of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona. After so many years, sometimes with partners for the broadcasts, the trip has become common. By early afternoon, she is back in the office. "With all the feedback I get, from the young to the elders, about how much they enjoy it, you don't want to turn them down," she said. "When we're not here, there's something missing in people's lives. That's how I look at it." Williams is behind her desk, but standing. There's already been enough sitting for the day. "A lot of the people don't read newspapers because they're uneducated," she said. "Mainly the elders. They get all their information from the radio. Those are the people I feel like I'm talking to -- 'Those of you who have penned up the sheep and had dinner, get ready for some NBA basketball.' "I feel that it's something that I'm giving back. My grandfather was a medicine man. He helped so many people across the reservation. He gave back a lot. I probably picked that up from him." Outside, it is another bright, crisp day. Down the street from the KTNN studios, five horses wander free, crossing roads with no apparent regard for cars and then stopping to graze in front of a building. People pay about as much attention as the animals paid to them. This is not like most other places. |

|

KTNN |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

|

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |