|

Canku Ota |

|

(Many Paths) |

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

|

December 30, 2000 - Issue 26 |

|

|

|

Dances with Buffaloes |

|

by Suzanne Ruta |

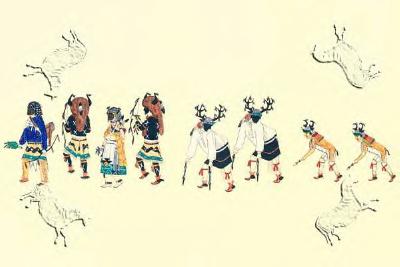

On Christmas

Eve at Nambe, a small (population 650) American Indian village and sovereign Indian nation, 20 miles north of Santa

Fe, the buffalo come out to dance by the light of a great bonfire. They come after evening Mass at the ancient

St. Francis of Assisi church, and dance for just a little while before returning to the kiva, the underground ceremonial

chamber, center of the pueblo's traditional religious life. With the buffalo come the deer, their horns circled

with sprigs of fir, like candles in Advent wreaths, the antelope and a couple of Pueblo Indians dressed up as their

old enemies, the Comanches, for comic relief. On Christmas

Eve at Nambe, a small (population 650) American Indian village and sovereign Indian nation, 20 miles north of Santa

Fe, the buffalo come out to dance by the light of a great bonfire. They come after evening Mass at the ancient

St. Francis of Assisi church, and dance for just a little while before returning to the kiva, the underground ceremonial

chamber, center of the pueblo's traditional religious life. With the buffalo come the deer, their horns circled

with sprigs of fir, like candles in Advent wreaths, the antelope and a couple of Pueblo Indians dressed up as their

old enemies, the Comanches, for comic relief. "Pueblo" is the Spanish word for village, and it is also used to describe the inhabitants. There are 19 of these villages — actually self-governing tribes or nations — encompassing 60,000 Pueblo Indians in New Mexico. The northern Rio Grande Pueblos arrived in the 14th century, after drought forced migration from the Four Corners area where their ancestors, known by their Navajo name, Anasazi, or Ancient Ones, built the great cities at Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. The New Mexico Pueblos speak three languages plus four dialects, as well as English. They work as farmers, government employees, Head Start teachers, and technicians at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. There are Pueblo doctors, lawyers, architects and of course artists. Pueblo jewelers and ceramicists sell their work over the Internet. Others work at the nine Pueblo gambling casinos. The casinos bring much needed income and (so far mostly low paying) jobs. But they are controversial. Joe Sando, a Pueblo historian, wonders who will teach the children to speak Keres, the southern Pueblos' language, if grandparents spend their afternoons at the casinos. In northern New Mexico, such worries may be premature. The old ceremonial life continues as in the past. On Christmas Day at sunrise, at Jemez and several other pueblos, the animals come down from the hills at sunrise. The buffaloes in great horned headdresses are accompanied by dainty buffalo ladies with their crowns of turkey or eagle or parrot feathers. The deer wear their bits of evergreen, as if bringing their mountain habitat right down into town. The animals dance again publicly on Jan. 6, Epiphany, or Three Kings Day, as it's called in New Mexico, following the Spanish custom, and throughout the winter months.  Dance is central to life in the pueblos, and goes on year round. Summer in the high desert of northern

New Mexico brings choral rain dances or corn dances, soothing and exhilarating. Winter, with a few exceptions,

is the time for powerful, dramatic re-enactments of life and death among the animals, the birth of tragedy from

the spirit of the hunt. When the Yale architectural historian Vincent Scully, in his passionate appreciation "Pueblo:

Mountain, Village, Dance," called the pueblo dances "the most profound works of art yet produced on the

American continent," it was primarily the winter dances he had in mind. Dance is central to life in the pueblos, and goes on year round. Summer in the high desert of northern

New Mexico brings choral rain dances or corn dances, soothing and exhilarating. Winter, with a few exceptions,

is the time for powerful, dramatic re-enactments of life and death among the animals, the birth of tragedy from

the spirit of the hunt. When the Yale architectural historian Vincent Scully, in his passionate appreciation "Pueblo:

Mountain, Village, Dance," called the pueblo dances "the most profound works of art yet produced on the

American continent," it was primarily the winter dances he had in mind.If only one could get the dates straight. The rich mix of Roman Catholic and native traditions the Pueblos observe means that some dances fall on fixed dates in the liturgical year. Dances that correspond to saints' days or to the Christmas cycle are generally open to the public. After that, things get murky. Ask about winter dances at Santo Domingo Pueblo, in the dusty plain south of Santa Fe, and you run into the famous Pueblo reticence, in its most charming, offhand form: "We don't put out a schedule. We don't specify in advance. But if someone calls and no one answers the phone, they can be pretty sure something is happening. We won't be in the office." Or try to pin down the date, in late February, of the beautiful deer dance at San Juan Pueblo, up in Rio Arriba County, and you run into a studied vagueness. The trick is to remember that although they are great theater — mysterious, powerful, moving and often humorous — Pueblo dances are not performances. They are communal prayers, religious ceremonies, linked in ways that outsiders will never understand to seasonal ceremonies, initiations, rites of passage, fasts, and retreats that the Rio Grande Pueblos — with their 460 years of experience dodging Spanish and American coercion and curiosity — do not perform in public, but out of sight, in the kivas, or in villages closed to outsiders for the day. Still, you can probably see a Pueblo dance almost any week this winter. But leave cameras, tape recorders, video equipment, even sketchbooks at home. A handout from Jemez Pueblo's Walatowa Cultural Center actually forbids "unauthorized publication of information." Failure to comply can bring trouble. When Santa Fe's daily paper, The New Mexican (now under a different owner), ran aerial photographs of the corn dance at Santo Domingo Pueblo years ago, the pueblo sued the paper for violation of its privacy laws. The paper printed an apology, in terms dictated by the pueblo. Like few events in our media- ridden world, then, Pueblo dances will not be televised, much less Webcast in real time. They must be seen live. But for anyone who has the patience, the gumption and the winter underwear to spend several hours of a January day outdoors in quiet watchfulness, the existential rewards are great.  For a city visitor, it's a spiritual exercise in itself to scale back to the right frame of mind.

On my first trip to New Mexico some years ago during a pause in the dancing at Santo Domingo Pueblo, I waved excitedly

to a new acquaintance across the plaza. When that venerable gentleman, who left Boston for the great Southwest

in 1942, glowered and turned away, I began to get the point. On the dancing ground, the "middle heart place"

between earth and sky, as it's called in the Tewa dialect, dancers and observers share a relaxed attentiveness

and quiet absorption in the matter at hand. For a city visitor, it's a spiritual exercise in itself to scale back to the right frame of mind.

On my first trip to New Mexico some years ago during a pause in the dancing at Santo Domingo Pueblo, I waved excitedly

to a new acquaintance across the plaza. When that venerable gentleman, who left Boston for the great Southwest

in 1942, glowered and turned away, I began to get the point. On the dancing ground, the "middle heart place"

between earth and sky, as it's called in the Tewa dialect, dancers and observers share a relaxed attentiveness

and quiet absorption in the matter at hand. Taos pueblo, the northernmost of the Rio Grande pueblos, is five miles north of the town of Taos. Architecturally it is the most traditional, with its two old squared-off hives five stories tall (and now mostly uninhabited), and it can feel like a wild place in winter, backed up against its sacred mountains with the Great Plains just beyond. This may be the best place in the world to see the deer dance (on Christmas or Three Kings Day). "In a snowy downtrodden clearing between the adobe cliffs, on the backbone of a continent" as Frank Waters memorably sets the scene in his classic 1950 study, "Masked Gods," the large chorus of deer file in, accompanied by the beat of drums and old traditional chants in Tiwa, the native dialect of Taos and Picuris Pueblos. Exactly how old are the chants? They go back farther than anyone can remember, according to Rina Swentzell, a Santa Clara Pueblo writer who frequently interprets Pueblo culture for the outside world. The Taos deer dancers wear whole deerskins with the head attached, just like old-time deer hunters, who, historians report, dressed as living decoys, in order to lure deer into ambush. Once caught, the deer were wrestled to the ground and suffocated. Imagine killing deer in hand-to- hand combat! The Taos deer dance is remote human memory made visible, history on the hoof. This celebration of winter, the season that winnows the herds, is full of tragic pathos. Farther south, in the gentle folds of the Rio Grande Valley, in late February, with the sacred mountains at a more comfortable distance, the San Juan Pueblo deer boys are a dashing lot. In their blue bandannas and white store-bought shirts worn open at the neck, they look like the chorus from the ballet "Rodeo." Their openwork white mesh leggings, furred moccasins, profusion of belts, garters, fringes, pompoms, tassels, jangling bells make a stylized and witty statement of what it means to be a deer. The bits of white fluff (cotton, eagle down?) and greenery about their persons suggest that this dance has to do with the weather. Like Groundhog Day, it roots for a quick spring thaw. The kiva is one pole of Pueblo ceremonial life. The other is definitely the kitchen, as visitors often discover on dance days, when impromptu invitations to lunch are common. Two years ago at Jemez, a hospitable family invited a friend and me to lunch in their small house near the plaza. From the street we walked right into a small living room with a table set for 20. A bunch of Navajo school kids were quietly mopping up a late breakfast or an early lunch. They had driven clear across the state to see the Jemez corn dance and late fall market. When they had finished eating it was our turn to heap our plates from the many bowls and platters on the table, with red and green chili, beans, pozole, turkey, ham, cole slaw, syrupy-sweet bread pudding, pumpkin pie and Cool Whip. As we ate, members of the extended family arrived from Albuquerque and points east and joined us at the table. In the adjoining kitchen, the matriarchs, stalwart grandmothers and aunts, worked and joked nonstop. They held things together in the pueblo, one felt, the way the crust contains the filling of a pie.  Most pueblos in northern New Mexico are open to visitors on ordinary days (when no dances or rituals

are being held). They may charge admission; they may also permit photography in some parts of the village, for

a fee. San Ildefonso, on Route 4, north of Santa Fe, is a great place to visit at any time. After the jumble of

shops in downtown Santa Fe and the clutter of billboards on Route 285 North, it's a relief to reach spacious, scattered,

undemanding San Ildefonso. Most pueblos in northern New Mexico are open to visitors on ordinary days (when no dances or rituals

are being held). They may charge admission; they may also permit photography in some parts of the village, for

a fee. San Ildefonso, on Route 4, north of Santa Fe, is a great place to visit at any time. After the jumble of

shops in downtown Santa Fe and the clutter of billboards on Route 285 North, it's a relief to reach spacious, scattered,

undemanding San Ildefonso.Here is a city-state of fewer than a thousand people living on 26,000 acres right down the hill from Los Alamos National Laboratory. How does it keep its balance, living between two worlds? Does it have to do with the messy old cottonwood tree to one side of the plaza or with the clear, familiar profile due north of the Black Mesa, the beloved humpbacked volcanic mountain? Of course it has to do with memory. San Ildefonso knows where it came from. And you can go there, too. Head on up Route 4, across the Rio Grande at Otowi, toward Los Alamos. Watch for the cheerful wooden "Welcome to Los Alamos, the Atomic City" sign on your right. A few yards past that early cold war relic, park on the left side of the road, and you're at the foot of Tsankawi mesa, home to a perfect pueblo in the sky, where no one lives. Tsankawi was built in the 15th century by San Ildefonso ancestors driven out of the Four Corners area by severe drought. But the lure of the river proved irresistible. By the late 16th century they had moved down to a less arduous life, on the banks of the Rio Grande. Now Tsankawi is part of Bandelier National Monument, run by the National Park Service. (No trace here of the fire that savaged Bandelier last spring. The burned-out area lies eight miles to the east.) In their jokey big brotherly way, the rangers have studded the steep narrow trail to the mesa top with stern but friendly warning signs. But even in midwinter, with the odd patch of ice on the trail, the half-hour climb is manageable. You can put your feet right into the niches worn into the soft white volcanic rock by generations of soft-shoed Pueblos. I've been here with arthritic elderly aunts and world-class mountain climbers.  Fifteen minutes up the trail you can stop at the first plateau and kneel beside the slight hollows

in the stone where women knelt to grind corn way back when, or you can trek on another 15 minutes to the top of

the long narrow butte, where the old multistory stonework complex has collapsed and gone to ground. But it's easy

to tell where the dance floor would have been. Just look for the place where the mountains are at eye level all

around. In one direction, the young, volcanic Jemez range; in the opposite direction, beyond a tender line of haze

above the Rio Grande gorge, the jagged snowy profile of the Sangre de Cristo range; to another side, a sequence

of pale pink mesas of volcanic tuff like this one, honeycombed with cozy, formerly inhabited caves. The difficult

thing at Tsankawi is not climbing to the top of the mesa; it's finding a reason to come down again. Fifteen minutes up the trail you can stop at the first plateau and kneel beside the slight hollows

in the stone where women knelt to grind corn way back when, or you can trek on another 15 minutes to the top of

the long narrow butte, where the old multistory stonework complex has collapsed and gone to ground. But it's easy

to tell where the dance floor would have been. Just look for the place where the mountains are at eye level all

around. In one direction, the young, volcanic Jemez range; in the opposite direction, beyond a tender line of haze

above the Rio Grande gorge, the jagged snowy profile of the Sangre de Cristo range; to another side, a sequence

of pale pink mesas of volcanic tuff like this one, honeycombed with cozy, formerly inhabited caves. The difficult

thing at Tsankawi is not climbing to the top of the mesa; it's finding a reason to come down again. |

|

|

|

|

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. |

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000 of Paul C. Barry. |

|

All Rights Reserved. |