|

Canku Ota |

|

(Many Paths) |

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

|

November 4, 2000 - Issue 22 |

|

|

By Bathsheba Demuth

|

Print and Color your own picture of a Caribou Old Crow Land of the Vuntut Gwitch'in The Tuktu and Nogak Project is a community driven effort to collect

and share Inuit ecological knowledge of caribou and calving areas in the Bathurst Inlet area of the Kitikmeot region,

Nunavut, Canada.

The Gwich'in people are asking us to support them in their efforts to President Clinton faces what is arguably the greatest conservation opportunity of our time in Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The biological, cultural, historic and scientific attributes of the area are so rich and uniquely entwined, and the ecological integrity of the area so vulnerable to proposed oil development, that presidential action is fully warranted. The combination of sweeping landscapes and rich biological diversity found in the Refuge, and especially its sensitive coastal plain, is unmatched anywhere in the circumpolar North. This extraordinary diversity stems in part from the high mountains of the Brooks Range which swing north against the Artic coast in northeast Alaska, compressing a full complement of Artic and subarctic landscapes and ecosystems into one compact unit. It is home to more than 180 species of birds, and numerous mammals including polar bears, musk ox, wolves, wolverine, moose, Arctic and red foxes, black bears, brown bears, and the white Dall sheep. Most compelling, the narrow coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge is the birthplace and nursery grounds of the Porcupine (River) caribou herd. The pregnant cows travel hundreds of miles to this unique place to give birth, then help their calves build strength before moving to wintering grounds in the boreal forest to the south. The great international migrations of the Porcupine caribou herd evoke breathtaking comparisons to Africa's fabled Serengeti, or to the now-lost thunder of buffalo across America's Great Plains more than 100 years ago. The Arctic Refuge was part of eastern Beringia, the ice-free plains of the last Ice Age. Its little known archeological and paleontological resources tell stories of old caribou corrals and coastal hunting camps, and may hold ancient clues to the days of the mammoth, giant beaver, and saber toothed tigers, and to the earliest peopling of the Americas. Above all else, it is the concurrence of so many globally significant expressions of ecological processes, biological and cultural diversity, and wild lands, on such a scale, and in one place, that sets the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge apart from even the greatest of our National Parks. It is the keystone, the "biological heart" of a larger region that includes the Yukon Flats NWR and the adjacent national parks in Canada -- the largest assemblage of protected natural ecosystems in the world. The Artic Refuge, established in 1960 by President Dwight Eisenhower, is still an inhabited wilderness. Two indigenous people, the Neetsa'ii Gwich'in of the mountains and boreal forest; and the Inupiat of the Artic coast still hunt, fish, gather plants, roots and berries, travel and live on these lands. Providing the resource base for the subsistence activities is an important purpose of the Refuge. The Porcupine Caribou Herd, in particular, is central to the culture of the Gwich'in, and to the economic and social fabric of their villages. Every Porcupine Caribou gets its start in life on the narrow coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge. Further West, the oil fields have displaced the Central Artic caribou herd from its traditional birthplace to alternate habitat further South. For the Porcupine caribou herd, there is nowhere else to go. In the face of intense oil industry pressure, Congress delayed a decision on protecting the Artic Refuge coastal plain's 1002 area when they passed the Alaska National Interests Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) in 1980. Even with strong public support for protecting the Artic Refuge, and 200 cosponsors for Wilderness protection this year, Congressional deadlock continues. The Arctic Refuge remains the unfinished business of ANILCA. The natural and cultural values of the artic Refuge are irreplaceable, rare, and far outweigh the temporary benefits, if any, of oil drilling there. With leading oil companies themselves looking "beyond petroleum" to improved auto technology and fossil fuel alternatives, and a growing appreciation of how conservation and technology development can impact energy efficiency, now is certainly the time to safeguard the highest and best of these lands for all future generations. For more information on this and the Gwich'in Peoples see the Gwich'in Steering Committee's

homepage at: http://www.alaska.net/~gwichin/index.html Write letters today to President Clinton who alone has the authority to ensure future

protection of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The President has made a historic gift to the nation in his

legacy of national monuments and conservation initiatives. In the Arctic Wildlife National Monument, he can protect

the most complete and important assemblage of Arctic and subarctic ecosystems in the world. This priceless fragment

of America's North will be a gift not just to America, but to the world; a legacy not just for our time, but for

all time. President William J. Clinton Dear President Clinton, The Gwich'in culture and way of life is intrinsically connected to the Porcupine Caribou Herd to meet all of their essential needs for survival. The Gwich'in are reliant upon the caribou for food, clothing, shelter, medicines, spirituality and tools. Beyond significance culturally, moreover the Gwich'in rely on the herd socially as well. Their ancient traditions are passed from one generation to the next at the time when the caribou is within the traditional homelands of the Gwich'in. The coastal plain is truly the biological heart of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The Gwich'in call this are "The Sacred Place Where Life Begins." Besides being the important birthplace to the caribou it is the denning area for Polar Bears, nesting area for 135 species of migratory birds and year round home to musk oxen. Designation of the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as a National

Monument is a legacy to all our future generations. A gift transcending time for all humankind. The culture, spirituality

and birthright of the Gwich'in will be preserved for their future generations. There are few opportunities such

as this, where human rights are recognized and environmental balance is preserved despite economic interests. Please

take the appropriate action in defense of life. |

|

|

|

|

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. |

|

Canku Ota is a copyright of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America"

web site and its design is the Copyright © 1999 of Paul C. Barry. |

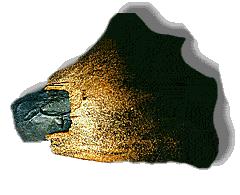

Old Crow,

Canada-What's remarkable is not just the antiquity and ingenuity of this tool, but its material: The scraper was

chipped from the femur of a caribou.

Old Crow,

Canada-What's remarkable is not just the antiquity and ingenuity of this tool, but its material: The scraper was

chipped from the femur of a caribou.