|

|

|

|

Outgrowing Bambi

Institute of American Indian Arts allows students freedom to create It's a native community. Alvin Sandoval, facilities coordinator, started working for IAIA as a mail clerk in

1990 but he began coming to the campus years before. Sandoval said the institute hosts a variety of artistic and cultural events that attracted

natives and non-natives throughout the year. And like many of the native people from the area, he'd offer a helping hand and that

developed into actually taking part in school activities. Sandoval said, "People got to know me. They liked me." And so when a job

opened up in the mail room, he applied and was hired. His wife, Carmen Henan, was also working at IAIA. Henan is the director for the Center

for Student Life. On a reservation, he said, there are different tribes but the people work together

and take part when there's a ceremony. Sandoval said at the institute, the people are always working but they combine their

efforts with traditional ways and thatís probably why the school continues to operate. IAIA opened as a high school with a certificate program beyond high school on the Santa

Fe Indian School campus in 1962. Over the years, the art work of the students caught the attention of U.S. presidents,

international art exhibitors, Hollywood actors and Life magazine .By 1975, the institute was offering an associate of fine arts certificate in two-dimensional

and three-dimensional design, museum studies and associate of arts degree in creative writing. And then in 1980, IAIA became homeless and had to move to the College of Santa Fe. Eight years later, Congress reorganized the institute and chartered it as the nationís

only fine arts college devoted solely to the artistic and cultural traditions of all American Indians. Just when IAIA was facing relocation from the Santa Fe area, in 1993 the Rancho Viejo

Partnership, Ltd., donated 140 acres of land for the school's permanent home. The students, faculty, staff and supporters held a groundbreaking ceremony for their

new campus on April 10, 1999, which they called, "Planting the Seeds for the Future." The groundbreaking and dedication involved a balanced and lively mixture of speeches,

acknowledgments, feasting, traditional dancing and singing, contemporary music and traditional prayers. "I think all Indian people know how to include tribal ways, old ways, because

everybody has that," Sandoval said. He said the institute teaches how each Indian nation has their own beliefs, values

and traditions but also how Indian people are one. Sandoval said in many urban towns and cities, there are usually Indian centers where

Indians can find other Indians. "That's important to us," he said. The institute is like an Indian center and school, Sandoval added. "The title, Institute of American Indian Arts and Alaska Native Culture and Arts

Development, says it all. That name encompasses all tribes," he noted. But Sandoval said the school has opened its arms to students from Canada, Germany,

South America and other international countries. Over the years, he said, he's noticed that a large number of the student population

have been Navajos and then Pueblos. Sandoval, who is from Pueblo Pintado, N.M., said IAIA has expanded its program to include

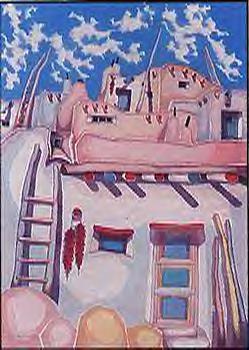

fiber arts, sculpturing, fashion, design and architecture. He said architecture is nothing new to natives who built their own homes and other

structures. The Navajo hogan is an octagon, which is a geometric design based on mathematics, Sandoval

explained. He said Native beadwork and weaving also rely on math. And Sandoval said natives had their designs in their minds, which demanded a huge amount

of thinking and reasoning. Kniffin said, "It's time for us to go further. Raw has more soul in it. It sees everything. "Instead of taking a glance (at life), catch the view. Art should always be done

for yourself. That makes it truly creative," he said. Kniffin, who wore a Kiss concert T-shirt, baggy pants, a pair of Nikes and his dark

black hair tied in the traditional Dine´ way, smiled as he looked over a huge black and white painting of

shadows. The shadows were Indian men with long loose hair who were trying to free Leonard Peltier.

Peltier peered down at them from a high small window with black bars in the middle of a prison wall. Kniffin said the prison window on the right side of Peltier, which had finger prints,

probably signified how Peltier was wrongly accused of killing of two agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The cell window to the left of Peltier had reverse lettering that spelled out Land

O'Lakes butter. There also was a picture of an Indian princess ó the Land O' Lakes decal. Kniffin said that cell window was probably a reflection of the stereotypes that American

Indians face daily. Kniffin said American Indian art should always be about raw inside emotions, about

how modern society affects American Indians, even if it's about paying bills, riff raft, or cultural shock. "What it's like to be a modern Indian and a young artist," he said as he

looked down the hallway at anther painting, which was a group of Kachinas. He said there's nothing wrong with using traditional American Indian images; it's just

time for the younger artists to focus on contemporary issues and distinguish themselves from older artists, like

Dan Namingha and Grey Cohoe. Kniffin admitted that he was a victim of Bambi art because it sold. He said he painted Apache Crown dancers until he ran out of paint because he could

get a hundred dollars for each painting. "That experience taught me what self-exploitation was. I've been trying to move

away from that ever since," Kniffin said. He said IAIA not only gives young native artists like him the opportunity to grow as

artists and to pass through the same school that the American Indian "greats" attended, but also to learn

about themselves, their culture, their people. "I didn't have that," Kniffin said slowly. But he said he wants to use his experience as an urban Indian, his heritage as a Dine´,

San Carlos Apache and Western Shoshone, and his awakening to his traditional side to "totally blow" American

Indian art into another level and then keep experimenting. Kniffin, a sophomore majoring in two-dimensional art, said he plans to continue his

art education either at Cooper University in New York City or at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. "I know where I'm coming from. And I'm not staying in the Bambi art mode, stereotypes.

It's always cool just to create," he said. As Kniffin turned to walk literally into the sunset, he stopped to answer one last

question: Who tied his hair? Kniffin looked down at his clothes, touched his hair, smiled and said, "I'm just

trying to represent my culture to its fullest and not be anything else." Institute of American Indian Arts

by Marley Shebala Navajo

Times Staff

SANTA FE

The Institute of American Indian Arts is more than a premier art college dedicated to indigenous cultures.

SANTA FE

The Institute of American Indian Arts is more than a premier art college dedicated to indigenous cultures.

During the dedication of the new campus on Aug. 26, which was called "Summer Harvest," Henan, several

other students and the new student housing were blessed by Mescalero medicine man Joey Padilla.

As Padilla prayed over Henen and the students, he gently placed brilliant amber markings on their faces.

Later that evening, when Henan explained blessing ceremonies that were conducted for the Cultural Center by Dine´

medicine man Raymond Jim and for the academic buildings by Cochiti spiritual leaders, she seemed oblivious to the

amber markings that were still on her face.

Like being on a reservation

Sandoval said, "Itís (IAIA) like being on a reservation."

Getting out of Bambi mode Garry Kniffin,

a 22-year-old Diné, San Carlos Apache and Western Shoshone, said he thinks it's up to the younger generation

of American Indian artists to push the limits of native art by getting out of the Bambi art mode and evolving their

art into the "raw" level.

Garry Kniffin,

a 22-year-old Diné, San Carlos Apache and Western Shoshone, said he thinks it's up to the younger generation

of American Indian artists to push the limits of native art by getting out of the Bambi art mode and evolving their

art into the "raw" level.

"We're still being oppressed but at the same time we exploit ourselves for pieces of silver. And we rely on

the federal government too much," he said as he continued to stare at the painting.

He said his grandma taught him how to tie his own hair and she also taught him why: "You have to be a respectable

person."

http://www.iaiancad.org/

![]()

|

|

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. |

|

Canku Ota is a copyright of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America"

web site and its design is the Copyright © 1999 of Paul C. Barry. |