|

|

Native American Music Finally Getting Recognized

by Richard Chang-Orange County Register

For years,

Native American music has been relegated to the folk, world and new age bins at record stores across the country.

For years,

Native American music has been relegated to the folk, world and new age bins at record stores across the country.

Or it would be tossed into the international or world-beat files -- a regrettable irony, since the music is about

as American as you can get.

But a revival of American Indian music has been taking shape over the past few years, and record stores -- and

the industry -- are finally paying attention.

The recent announcement of a "best Native American music album" category at the 2001 Grammy Awards officially

marks the genre's arrival.

That didn't happen overnight: The New York-based Native American Music Association has been lobbying the Recording

Academy for the category since the mid-1990s.

The number of albums released by American Indian artists each year has almost tripled since 1994, said Ellen Bello,

CEO and president of the Native American Music Association.

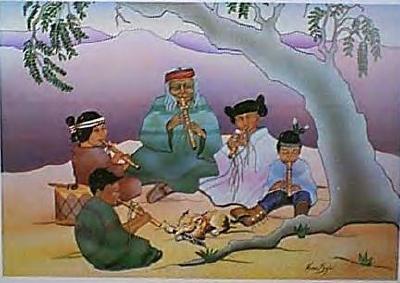

Of course, tribes have been performing powwow, peyote and ceremonial songs for hundreds of years. But recorded

music by Indians for Indians (and a broader audience) isn't much older than rock 'n' roll itself.

In 1951, Ed Lee Natay recorded "Navajo Singer" on Canyon Records, a collection of Navajo, Hopi, Kiowa,

Tewa, Zuni and Pueblo songs.

Navajo and Ute flutist R. Carlos Nakai recorded his first of many albums on Canyon in 1982. His 1989 album "Canyon

Trilogy" is the first American Indian gold record, with more than 500,000 copies sold.

Activist John Trudell (Santee Sioux) and singer-songwriter Bill Miller (Mohican) are often cited as the first artists

to bring the music -- mixed with rock, folk and country -- to a wider, non-Indian audience. Trudell has long collaborated

with Jackson Browne, and Miller has toured with Pearl Jam and Tori Amos.

But it was Robbie Robertson (Mohawk), legendary guitarist for The Band, who really broke down mainstream doors

with his remarkable 1994 album "Music for the Native Americans," a soundtrack for a documentary series

on the Turner TV network.

Robertson brought together a host of Indian artists, including Ulali, Coolidge, Kashtin, the Silvercloud Singers

and Jim Wilson. The album combines traditional chants and instruments with rock and electronic effects.

"No one knew about his Indian heritage until that recording," Bello said. "He was pivotal in launching

the movement. While a lot of artists were doing the same kind of work at the same time, Robertson had more mainstream

success."

Robertson pushed the genre even further with 1998's "Contact from the Underworld of Redboy," a fantastic

mix of rock, Indian sounds, hip hop and electronics.

While underappreciated in terms of sales, "Contact" did earn Robertson a Grammy nomination -- in the

world music category.

The mixing of genres has left some traditionalists shaking their heads. Some Indian music is considered sacred,

and sampling a chant, combining it with electronic sounds or even playing it on the radio is forbidden.

"It's like playing with dynamite," one artist told Bello. "You have to be real careful."

Most Indian musicians have been. "There is a cause for concern from the traditional perspective," Bello

said, "but (artists) know that if traditional elements need to remain private, they will be."![]()

|

|

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. |

|

Canku Ota is a copyright of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

|