|

|

The Art of Learning Tim Rollins and K.O.S. Art: Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (After Harriet Jacobs) I See the Promised Land...

by Randy Gragg Newhouse News Service Seattle Times

PENDLETON,

Ore. - Decked out in black, from his short-brimmed felt hat to his Italian shoes, Tim Rollins has sauntered into

Pendleton looking as if he's starring as "the stranger" in a spaghetti Western.

PENDLETON,

Ore. - Decked out in black, from his short-brimmed felt hat to his Italian shoes, Tim Rollins has sauntered into

Pendleton looking as if he's starring as "the stranger" in a spaghetti Western.

He could be a card shark or maybe a traveling salesman, but what he calls himself is even more suspect: "a

conceptual artist whose medium is education." He's come to the United Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla

to make a painting. The subject is Shakespeare. And the materials he's using are watercolors, fine paper and about

a dozen kids.

"We're gonna make some art," he raps in hip-hop rhythm. "But we're also going to make history -

and maybe a little hysteria."

During the past 20 years, Rollins has made a lot of art, some fascinating history and stirred up his share of hysteria

with a program he called Kids of Survival, better known simply as "Tim Rollins + K.O.S."

Rollins, who lived for 15 years with the beehive-haired B-52s singer Kate Pierson, has, in the cutthroat New York

art world, been regarded as both hero and scourge.

In the early '80s, unable to make a living as an artist, he took a job teaching in the South Bronx but quickly

became frustrated by the system's treatment of learning-disabled kids. So he wrote a grant to the National Endowment

for the Arts to start K.O.S., then conceived to be an after-school program. Soon after, he discovered gold in an

act of vandalism: One of the kids drew a picture in one of Rollins' favorite novels.

Working with a group of mostly Latino teenagers from the South Bronx, Rollins made collaborative paintings based

on great literary works by, among others, Franz Kafka, Herman Melville, Stephen Crane and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

In the booming '80s art market, they fetched as much as $100,000 each.

Now, as an art-world fashion, K.O.S. is long passe. But as Rollins' personal mission, it's expanding

into its third decade. He still works with a core group of kids in a warehouse in Manhattan's Chelsea district,

meets regularly with similar groups in San Francisco and Memphis, Tenn., and teaches workshops in such far-flung

locations as Bristol, England, and Des Moines, Iowa.

Now, as an art-world fashion, K.O.S. is long passe. But as Rollins' personal mission, it's expanding

into its third decade. He still works with a core group of kids in a warehouse in Manhattan's Chelsea district,

meets regularly with similar groups in San Francisco and Memphis, Tenn., and teaches workshops in such far-flung

locations as Bristol, England, and Des Moines, Iowa.

In late June, he brought his program to the Crow's Shadow Institute in Pendleton, a studio school founded by Oregon

painter James Lavadour for the artists and kids of the Confederated Tribes.

Based in an old mission school a couple hundred yards from the still-visible wagon ruts of the Oregon Trail, Crow's

Shadow is the most rural place city-slicker Rollins has ever worked. To assist in this five-day workshop, he's

brought Nelson "Rick" Savinon, who joined K.O.S. at age 13, more than 15 years ago. This is the first

time they've attempted to stitch Native Americans into the ethnic fabric of K.O.S. But Rollins' patois remains

high-speed, urban and 100 percent about ambition.

"Nobody fails in my class," he says, raising his head with a punctuating blink of the eyes. "It's

not allowed."

The trick to avoiding failure is in the structure. Rollins covers a canvas in pages of the inspirational text.

Then he has the students paint small motifs, something they can infuse with a sense of themselves.

On the pages of "Red Badge of Courage," for instance, Rollins had his "at-risk" kids "paint

your wounds." On "The Scarlet Letter," they made their own letters of martyrdom. For "Animal

Farm," the kids, many of whom often couldn't name the vice president, learned enough about the world's leaders

to caricaturize them as farm animals.

Painted on thin, semi-translucent, banana-fiber paper, these individual pieces can be seamlessly pasted onto the

canvas like decals. The result becomes a constellation of individual creative ferment exploding across the pages

of literature.

At Crow's Shadow, 15 kids will make a painting based on Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night's Dream." The

motif is "love-in-idleness," the magical flower Puck uses for his mischief.

"It's about how complete faith in an illusion can become reality," Rollins says. "That's what art

is all about."

In a weeklong workshop, time is short. So Rollins offers a multimedia Cliffs Notes version of "A Midsummer

Night's Dream" - lecturing, reading key passages, playing Felix Mendelssohn's incidental musical score for

the play and watching in daily segments Peter Hall's 1968 movie version, starring Ian Holm as Puck, Ian Richardson

as Oberon and Judi Dench as Titania, among others.

He teaches the play as an allegory of creativity with the charm of a drill sergeant.

Rollins: "Who wrote the incidental music?"

Class: "Mendelssohn?"

Rollins: "Don't say it like a question. Say it like you know it."

Class: "Mendelssohn!"

Rollins: "Who is Puck?"

Class: "A servant."

Rollins: "But what's his power?"

Class: "He's a trickster."

Rollins: "Yes, he can transform things. Like an artist."

He ends each of these Q & A sessions testing the kids' memorization of a passage that he believes goes to the

heart of art making.

Rollins: "As imagination bodies forth . . . "

Class: (mumbles)

Rollins: "Come on. You know whole songs by Britney Spears. You can learn one passage from Shakespeare."

Rollins and the class: " . . . The forms of things unknown / The poet's pen turns them into shape / And gives

to airy nothing / A local habitat and a name."

James Lavadour shaped a new local habitat and name in the Crow's Shadow Institute. A blend of Cayuse, Walla Walla,

Umatilla and French blood, Lavadour, a self-taught artist, has lived his whole life here. But inspired by the surrounding

landscape that fills his sublime canvases, Lavadour has become one of Oregon's most nationally recognized artists.

Art, Lavadour says, has been his door to a life beyond the reservation, one he wants to open to more Native Americans.

And, so in 1992, with a grant from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and several thousand dollars of his own money,

Lavadour started the institute.

The original idea was to become "a portal" for first-rate artists to come and make their

own work, teaching by example. "I want people to have significant experiences here," Lavadour says.

The original idea was to become "a portal" for first-rate artists to come and make their

own work, teaching by example. "I want people to have significant experiences here," Lavadour says.

But Lavadour and his staff discovered that another of the tribes' yawning needs is to provide bored teens with

"significant experiences." And, so, in an effort to push beyond kids' art classes, he invited Tim Rollins,

to see "what we can learn from how he teaches."

Concurrent with the Shakespeare crash course, Rollins re-teaches the kids how to draw. His first rule is to forget

the rules. What's more important is intensity.

"Art is not fun," Rollins cautions. "It's really hard fun."

He has the students pore through art books making lists of their 10 favorite paintings of flowers. Then, with thick

crayons, he has them draw flowers on huge sheets of butcher paper, over and over and over again. At first, the

drawings actually look like flowers. But Rollins' constant cajoling "to find the power" gradually causes

them to blossom with ever-more-exuberant patterns and abstraction.

The budding artists then receive bottles of the highest-quality watercolors and sheets of the banana-fiber paper.

The arm-size gestures of colored lines are rechanneled into implosive, tiny blurs of spectacular color. The kids

make hundreds, experimenting and perfecting their technique. Rollins and Savinon select the best and begin gluing

them to the canvas.

"Drawing isn't just drawing in this class," says Portlander Shayleen Macy, 14, a member of the Warm Springs

tribe. "I'm learning why I'm doing it. It's like the play says, beauty isn't just in the eyes, it's in the

mind."

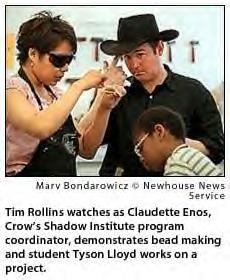

Tyson Lloyd, 12, a member of the Confederated Tribes, seems to have one of Rollins' six senses all to himself.

The first day of the workshop, Lloyd was all but mute. But by day three, thanks to Rollins' constant visual and

verbal taunts, he is working feverishly shoulder-to-shoulder with much older students. By day four, Lloyd gives

a radio interview.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is Raven Feather Price, 15, from Seattle. She is clearly both

talented and confident, so Rollins enlists her in the obviously more serious work of assembling the collage. Sensing

that her ability always has won praise, Rollins matter-of-factly corrects her positioning of the flowers. Angered,

she drifts away, but by day's end, she's back working side-by-side with Rollins and Savinon.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is Raven Feather Price, 15, from Seattle. She is clearly both

talented and confident, so Rollins enlists her in the obviously more serious work of assembling the collage. Sensing

that her ability always has won praise, Rollins matter-of-factly corrects her positioning of the flowers. Angered,

she drifts away, but by day's end, she's back working side-by-side with Rollins and Savinon.

"Tim taps right into you," says Savinon, the K.O.S. veteran, whose grinning, easygoing manner frequently

provides the kids a buoy in Rollins' storm. "I see it with these kids' faces: Who is this guy? But you find

yourself constantly trying to impress him. He pushes you to the edge and then lets you decide whether to fall off."

Like the paintings he orchestrates, Rollins wears plenty of his own wounds, letters of martyrdom and flowers.

Rollins' career began as a studio assistant for the famously curmudgeonly language artist Joseph Kosuth. Rollins

co-founded the noted political art collective Group Material.

Blending Kosuth's theories on using text as a material and the working methods of Group Material, Rollins evolved

accident into method. The resulting paintings quickly found buyers in the junk-bond-fueled late-'80s New York art

market, and K.O.S. became a for-profit company, paying the kids' salaries. But as stylish dealers sold Tim Rollins

+ K.O.S. paintings to collectors and the Museum of Modern Art, leftist academics blasted Rollins for everything

from his exclusive use of the Western canon to featuring his own name on the K.O.S. marquee.

Then in 1991, as the art market was crashing, K.O.S. took a machine-gun blast of ill fortune: Its youngest member

was randomly murdered; the group's most loyal collector died of AIDS; Rollins and Pierson broke up; and New York

magazine published a devastating article in which several ex-K.O.S. members charged Rollins with exploitation and

mental instability.

Rollins claims his accusers were vengeful after being kicked out of K.O.S., a contention echoed by Savinon, who

says, "If you knew them, you wouldn't believe them." But K.O.S.'s art-world stock plummeted.

"I could barely get out of bed for months," Rollins recalls. "But when you've started out with nothing,

you remember how to live with nothing. We pressed on."

At the end of the week, the painting stands as a testament to the week's work. It is a radiant object, collaged

with "love's wounds" and twinkling with the beads in a nod to traditional Native American arts. And whether

Rollins is a salesman, actor, preacher or another trickster like Puck, it's clear he has conjured not just an artwork

but several far more serious artists.

"Now I understand what art really is," Shayleen Macy says. "Anybody can draw a flower. But art is

about imagining what you want to see.

"I've changed a lot in these last five days," she adds, "in ways that aren't going to go away."

http://www.diacenter.org/kos/home.html

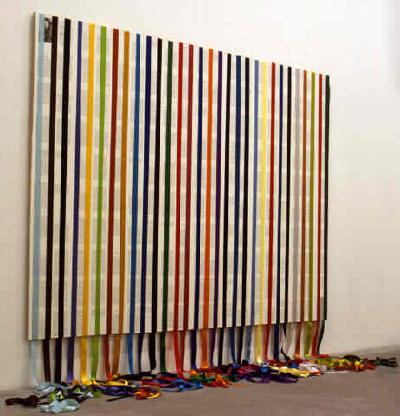

Work Date 1998

Category Mixed Media

Medium Book pages & satin ribbon on linen

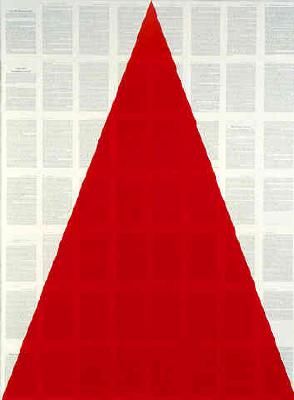

Work Date 2000

Category Painting

Medium Pencil and acrylic on bookpages on canvas

![]()

|

|

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. |

|

Canku Ota is a copyright of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

|