|

|

Teaching to Reach Out

Educators Learn to Identify, Work Against American Indian Prejudices

by Steve Kuchera Duluth News Tribune Staff Writer

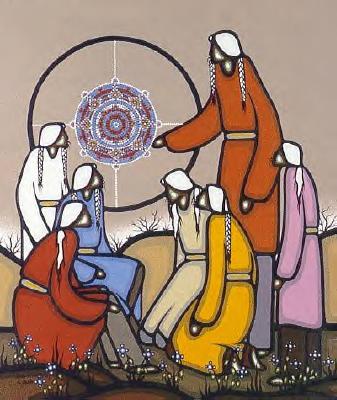

artwork by Leland Bell

When Gary

Johnson recently asked his college students to visualize an American Indian, their collective image was a dark-skinned

man in buckskin and feathers. When Gary

Johnson recently asked his college students to visualize an American Indian, their collective image was a dark-skinned

man in buckskin and feathers.Not a woman, not a doctor, not a person dressed as you would expect to meet in everyday life, student Ryan Schmidt recalls. The exercise helped make the eight students in Johnson's Native American Cultural Awareness for Educators class at the University of Wisconsin-Superior aware of their preconceptions of American Indians. "It's interesting; there's so much I didn't know,'' said Schmidt, a Carlton resident studying to be a social studies teacher. "The biggest things were stereotypes I didn't even know I had.'' Schmidt said the class will make him a better teacher -- more sensitive to cultural differences and able to promote understanding between cultures. That was Johnson's goal when he created the three-week summer class five years ago. "I'm not trying to turn these people into Indians,'' said Johnson, the director of the UWS Center for American Indian Studies. "I'm trying to make them more aware of Indian issues.'' Johnson, a member of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, knows what it's like to attend schools that, when they addressed American Indians at all, did so from a white perspective. "It used to be if you wanted to do good in school, you had to stop being Indian,'' he said. "I wanted to change that.'' Changing that could reduce a drop-out rate among American Indians that is higher than all other racial and ethnic groups in the United States. According to a 1994 study by the National Center for Education Statistics, 25.4 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native students who should have graduated from high school in 1992 had dropped out of school. Researchers say one reason for the high drop-out rate is that schools promote the values and views of the dominant culture, alienating minority students. "They are usually long gone before you realize there's a problem,'' Johnson said. "You have to reach these kids or they turn away.'' Reaching minorities is just one reason to teach about their cultures; increasing understanding and reducing conflicts are others. In 1983, the escalating battles over treaty rights -- including the springtime spearing of walleye -- prompted the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe to form the Ad Hoc Commission on Racism. The commission's work led the Wisconsin Legislature to pass laws requiring K-12 schools to teach about Wisconsin's 11 American Indian tribes and bands. The laws, enacted in the 1989-1991 budget years, are collectively known as Act 31. Johnson, who is doing his doctoral dissertation on Act 31's effectiveness, said the act was a good idea that hasn't fulfilled its promise because many teachers cover Indian issues separately from other topics. That sends the message that Indian history, government, literature and treaty rights are not as important as other topics, Johnson said. He says teachers should integrate Indian issues into existing classes. "You take what you are already doing and change it a little bit to make it more inclusive,'' he said. "It's so easy to do, to make education more accessible.'' Johnson's students learned about federal Indian policy, tribal government, treaty rights, literature, spiritual beliefs and stereotypes. "It's probably one of the best classes I've ever taken,'' said Mellen resident Pat Gretzlock. "I can stand here and tell you I don't have a racist bone in my body. But I would be lying -- we all do.'' The class improved Gretzlock's awareness of Indian issues and values. Gretzlock teaches middle school social studies in Drummond and has American Indian relatives and students. "It's kind of hard to relate to them if you don't have a clue,'' he said. In addition to attending classroom lectures, the students visited Madeline Island, which has a long Ojibwe history, and the Lac Courte Oreilles Indian Reservation. Standing in an ancient pipestone quarry near a small stream flowing through a maple forest, the students listened as Ojibwe storyteller Jerry Smith prayed and offered tobacco to the spirits, asking for permission to tell the Ojibwe creation tale out of season (the tale is traditionally told only during the winter) and to take a small amount of pipestone. The red stone, used to make pipe bowls, represents blood and life. "This is a holy place, a sacred place,'' Smith said. As he prayed, the sun broke through the clouds. Smith took the sign as a blessing and told the students several stories providing insight into Ojibwe beliefs and values. "I thought Jerry was amazing,'' Duluthian Jason Brandt said later. ``He had a great way about him. It was hard not to learn from him.'' Brandt is studying to become a social worker. He took the class to get a better sense of American Indian history and how it affects Indian culture. "It's been thought-provoking,'' he said. "I learned a lot you don't in school.'' |

|

|

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. |

|

Canku Ota is a copyright of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

|