|

|

Humboldt State Program a Model for Training Humboldt State program a model for training Native American teachers For details about the book or ITEPP, call (707)-826-3672 or visit Humboldt-ITEPP NCIDC

Native American Teachers

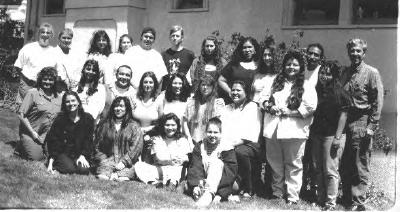

Photos: Group One ITEPP class of 1969; Group Two ITEPP class of today

![]() ARCATA,

Calif. — Seeking to stem the staggeringly high school-dropout rate among American Indian students, in the late

1960s tribal leaders and educators agreed that Native students would respond better to Native teachers.

ARCATA,

Calif. — Seeking to stem the staggeringly high school-dropout rate among American Indian students, in the late

1960s tribal leaders and educators agreed that Native students would respond better to Native teachers.

To create that pool of educators, they started the nation's first Indian teacher-training program on the campus

of Humboldt State University. There amid the California redwoods, in the state with the second-largest Indian

population, they selected 18 students - seven men and eleven women, representing the Hopi, Cherokee, Pomo, Mission,

Washoe, Pit River, Hupa and Yurok tribes -- who began rigorous, year-round training.

The short-term result? Although given no assurances when they started, most of the 18 got jobs.

The long-term result? The trail-blazing Indian Teacher and Educational Personnel Program (ITEPP) at Humboldt has

since trained hundreds of students for careers serving Native communities and continues to foster innovation.

The short-term result? Although given no assurances when they started, most of the 18 got jobs.

The long-term result? The trail-blazing Indian Teacher and Educational Personnel Program (ITEPP) at Humboldt has

since trained hundreds of students for careers serving Native communities and continues to foster innovation.

The program, which was initiated to create classroom role models, has itself become a role model for similar Native

teacher-training programs throughout the U.S., Canada and Australia. Recently, in conjunction with Humboldt's commencement

ceremonies, ITEPP celebrated its 30th anniversary, a reunion that brought together generations of ITEPP participants.

"When we started, many of the schools in tribal locales were racist and perpetuated colonial oppression,"

says ITEPP Director Laura Lee George, a Karuk who is herself a graduate of the program. "In contrast, we knew

what worked and what didn't work with Indians."

"These first students were so important to prove that Indian students, first of all, could graduate from college,

because at that time there were only five Indian graduates from Humboldt State."

The program drew would-be teachers from all over California -- and they would have come from further afield if

not for prohibitive out-of-state tuition costs. Many represented tribes along California's "Redwood Coast,"

such as the Yurok, Karuk, Wiyot, Pomo, Tolowa, Tsnungwe and Hupa. Others -- Navajo, Hopi, Tlingit, Shoshone, Abenaki

-- were drawn from as far away as Maine; "the result of government relocation programs," George explains.

Despite enrollment restrictions and other impediments, the program has chalked up an astonishing record of success.

More than 90 percent of the students finish the program and graduate, a higher completion rate than most schools,

including Humboldt. In comparison, the national Indian dropout rate has been as high as 60 percent at some institutions.

"If we can get them here, we can get them through," says George. Among the hundreds to go through are

Andy Andreoli, who now directs Indian programs for the California Department of Education; Loren Bommelyn, noted

linguist and author of the Tolowa dictionary; and Pamela Malloy, the first ITEPP graduate to get a teaching job,

who continues to teach at a Eureka elementary school.

Praised by the U.S. Department of Education as one of the nation's foremost forces in producing American Indian

and Alaskan Native educators, ITEPP seeks to prepare qualified professionals who can teach the basic academic public

school curriculum "without compromising the tribal and cultural identities of Indian students," George

adds.

The focus of the program expanded in the mid-1980s to embrace educational personnel -- social workers, administrators,

guidance counselors and tribal service professionals -- as well as teachers. Enrollment was increased, with as

many as 60 students in recent years, although the average is about 35 to 40. Many applicants still have to be turned

away.

Expectations of the students are high. In the early years, they took regular degree programs during the academic

year, credential courses during the summer and special cultural classes throughout the year. On spring breaks,

they made field trips to reservations, tribal education programs and Bureau of Indian Affairs schools.

Nowadays, each student also signs a "participation agreement" that includes such stipulations

as weekly seminars, fieldwork offering direct experience with Indian students and proficiency in computer technology.

In this era of teacher shortages because of smaller class sizes, the hard work pays off: ITEPP has a 100 percent

graduate employment rate, according to ITEPP coordinator Phil Zastrow.

Nowadays, each student also signs a "participation agreement" that includes such stipulations

as weekly seminars, fieldwork offering direct experience with Indian students and proficiency in computer technology.

In this era of teacher shortages because of smaller class sizes, the hard work pays off: ITEPP has a 100 percent

graduate employment rate, according to ITEPP coordinator Phil Zastrow.

Still the only program of its kind on the West Coast, ITEPP also operates a curriculum resource center with books,

videos, periodicals and other archives for research on Indian-related subjects, including health, history, children's

literature and legislation. Buffy McQuillen, another ITEPP graduate, coordinates the center, which is open from

8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. weekdays. She emphasizes that its materials are available to anyone.

(For details, call McQuillen at (707) 826-5199.)

This year the program added a new minor in American Indian education, which ranges over the history of Indian education,

and covers counseling, grant-writing, social and cultural considerations; and a graduate student at Vermont's Bennington

College is taking one of the courses long-distance via the Internet.

Closer to Humboldt, ITEPP's influence also extends beyond the campus. George and others on a task force of educators

and tribal leaders are creating a trail-blazing "magnet school" for Indian education in Crescent City.

It is a collaboration among Del Norte County Schools, four local sovereignties -- the Yurok tribe and the Smith

River, Elk Valley and Resighini rancherias -- and programs such as ITEPP and the Northern California Indian Development

Corporation.

According to George, the new school, which starts in September, will give high school students a chance to take

"a curriculum that revolves around American Indian issues rather than on a colonization model which focuses

on the westward movement of Europeans."

Such a curriculum is at the heart of a proposal now working its way through the California Senate. The measure,

SB 1439, would require the state's Department of Education to craft a model curriculum on Native American history

and culture.

The proposal acknowledges that, despite recent efforts to recognize diversity, education about Native Americans

remains limited and out-of-date. In the view of State Senator Dede Alpert of San Diego, "There are more than

100 California Indian tribal governments. It is time that the state develop a curriculum for its students that

acknowledges Native American history, culture and tribal sovereignty in a comprehensive way."

Del Norte County Schools, working with ITEPP, has spent the past four years developing such curricula, George says.

Passage of the measure, she adds, would help "debunk white-dominated history, concentrate on breaking stereotypes

and explain just where the real history is buried."

An example of such debunking is ITEPP's publication of a "response" to California's celebration of the

Gold Rush. Conceived by George and carried out by the dozens of ITEPP students, "Northwest Indigenous Gold

Rush History: The Indian Survivors of California's Holocaust" is a collection of personal interviews with

local Native elders, archival photos and literature reviews -- all intended to paint an unromanticized picture

of Native devastation by the gold-crazed 49ers.

ITEPP alumnus Chag Lowry, the editor, said the aim was to create an account for use in classrooms that offered

"a more balanced and realistic view of history...in order to create a better understanding between cultures

and pave the way for healing in Native communities."

http://www.humboldt.edu/~hsuitepp.

Office of University Communications Siemens Hall 130

public@humboldt.edu Complete contact information

--

André Cramblit, Operations Director

The Northern California Indian Development Council NCIDC is a non-profit organization that meets the social, educational,

and economic development needs of American Indian communities. NCIDC operates a fine art gallery featuring the

Tribes of N.W. California.

(http://www.ncidc.org)

(http://www.americanindianonline.com)

![]()

|

|

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. |

|

Canku Ota is a copyright of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

|