|

PALA INDIAN RESERVATION -- It's hard to miss Nadeane Nelson in this rolling backcountry

enclave. She's the 81-year-old great-grandmother in the red sports car.

She cuts an imposing figure walking across the leafy heart of the reservation: perfect posture beneath her flowery

dress, her always-moving arms adorned with turquoise and silver.

Now the state of California, the local school district and a stranger have teamed up to let more people know this

small woman who comes from the very root of this place.

Making it happen is Ross Talarico of Escondido, a quiet poet and ex-professor with great exuberance for the ideal

that common language and memory connect and elevate us.

His life's work has been preserving oral histories of elders such as Nelson from communities like Pala, because

he believes they hold the power to save society.

"When an old person dies, it's like a library burning down," Talarico said.

His writings on community-building through language have won him great acclaim, including a regular newspaper column,

appearances on network television and endorsements from such renowned writers as Studs Terkel.

His efforts have been directed toward Pala, home to many disadvantaged youths, via a three-year state grant administered

by the Bonsall Union School District, which runs a charter school on the reservation.

Talarico is working to build the language skills of the youngest members of the community to help them better fulfill

the human need for self-expression.

At the same time, he is drawing out the community's history. The plan is that these two threads will knit together

and form a stronger fabric of life.

One recent afternoon, Talarico brought Nelson together with a group of children from the reservation.

At times the meeting grew awkward, with neither generation knowing quite how to handle the other.

But as they talked, two of the boys and Nelson discovered they are related. Nelson was delighted to learn from

12-year-old George Subish that the kids still like to put together homemade cars and race them down the hills,

as they did in her day. At times the meeting grew awkward, with neither generation knowing quite how to handle the other.

But as they talked, two of the boys and Nelson discovered they are related. Nelson was delighted to learn from

12-year-old George Subish that the kids still like to put together homemade cars and race them down the hills,

as they did in her day.

Nelson leaned attentively toward 13-year-old Mario Aguayo, his hair slicked down neatly and respectfully for his

meeting with her. He read her his poem about an eagle.

She looked at him thoughtfully for a moment and said: "I have an eagle at my house, a picture on my wall.

I see him soaring really high, soaring to places that I've never been. I think we should always try to be like

that eagle, soaring our highest."

Afterward, she said: "That boy with the eagle poem -- the eagle is very important to our people. He should

have grandmothers to tell him about the eagles."

But she already knows why the Pala Indian Reservation has lost so many generations that once linked the people

together. Pala is the land the government forced her ancestors onto at the start of the 20th century, when speculators

and ranchers started taking over the mountain region outside Warner Springs, where her people had lived.

Only too soon, economics would force many off their reluctantly adopted land.

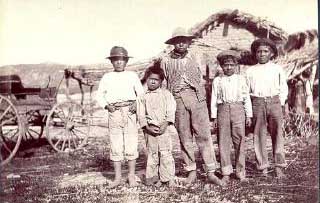

At the time of the Removal of 1903, as it is called here, Nelson's great-grandmother Manuela Griffith was already

a force among the native people. In Talarico's telling of Nelson's oral history, Manuela was a tiny woman born

during the California Gold Rush who had married a white cowboy named Fred and learned to fend for their family

when he was off on cattle drives.

Manuela's independence and ability to live in both cultures was passed on to her daughter, Salvadora, who became

one of the main teachers on the Pala reservation.

It was Salvadora who taught the mountain people what they needed to survive in their new world: basic hygiene,

sewing, carpentry, housekeeping and Catholic catechism, now that their lands centered on the Mission San Antonio

de Pala.

Like her mother, Salvadora married a cowboy, a Spanish-Indian named Valenzuela, and also learned to take care of

their family during his long absences. She set up businesses providing work for the Pala band picking chili peppers

and doing fine needlework and weavings for the outside world.

Many of Pala's women were schooled in domestic work so they could hire out to the rich white families in Los Angeles

and Beverly Hills, where Salvadora herself had worked for a time to earn enough money to build her own home. Always

with the future in mind, she built her house big with enough rooms to rent out to the many prospectors who stayed

because there were no hotels around, and the historians and professor-types who came after the Removal to study

the ways of the tribe.

The red house remains standing on the reservation.

"Their impact was everywhere then," Nelson said. "Now, I'm not so sure what is left."

The global perspective -- that none of the greatness of her ancestors matters anymore -- starts to depress her.

But she brightens at the memory of a small, personal moment.

"Just the other day I was here, and a woman told me that her husband remembers being taught English by my

grandmother," she said, straightening her neck, which was draped with delicately beaded necklaces.

Her mother, Claudina, had suffered from tuberculosis, which was a death sentence in those pre-antibiotic days,

so the family kept the child away from her. Her strongest and happiest memories are of her grandmother and being

raised here on the reservation.

Nelson left for a time after she married a combat pilot, a cowboy of sorts, and also had two daughters and learned

to fend for herself during his long absences.

For a time, she did bookkeeping, ran a laundry, and had an Indian goods store near the Bully's restaurant in Del

Mar. Now she works at Pala's Cultural Center, helping visitors learn about the tribe.

With the help of Talarico, the school and the state, Nelson will be picking up the threads of her ancestors and

will become, in her own way, a teacher to her people.

CALIFORNIA INDIANS AND THEIR

RESERVATIONS:

http://libweb.sdsu.edu/sub_libs/pwhite/calinddict.html

A History of American Indians

in California

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/5views/5views1.htm

Pala Band of Mission Indians

http://www.palaindians.com/default.htm

|