|

|

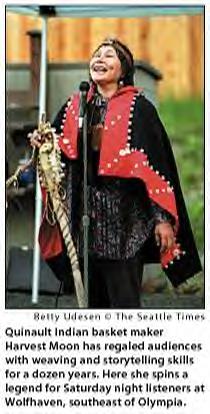

Basket Weaver Harvest Moon:

"We Need to Share our Tradition"

by Marc Ramirez Seattle Times

|

Now Harvest Moon sits at the head of a dining-room table around which are seated 14 women, each anxiously clutching strips of cedar bark as fog sneaks over the forested mountains outside. She guides the women through a series of twists and pulls. Raffia twine winds a serpentine path through the folded bark and binds it together in a small patchwork - the beginnings of a small basket. "Give it a little tug," she says. "You'll feel it pull and tighten." Moon's own handiwork decorates the table - cedar baskets ringed in modular designs and filled with the multicolored raffia, a leaf brought to the Pacific Northwest by settlers, she tells them, who used it to pack glassware. "The bottom of the basket - what you just did - is the hardest part," she says. The tradition is to give your first basket away, preferably to a young girl, in hopes she will become a weaver. Whatever works. Not long ago, Native American basket weaving was falling apart at the seams. In 1995, when Washington's native basket makers held a summit at Evergreen State College, they lamented the fact that few young tribal members at the time were pursuing the craft. A skill requiring patience in a world of instant gratification, it also got kids to wondering: How could anyone make a living at it? Moon, however, a member of the Quinault tribe of Washington's Olympic Peninsula, has been a professional weaver for nearly 10 years. Round-faced, with deep dimples and a demeanor as bright as her name, she is 43, among only a handful of basket weavers of her generation. Her weaving and storytelling skills have led to elementary school artist-in-residence positions, lecture circuit gigs, fair and festival exhibitions and classes like this one in Darrington. At the table, the women, all of them white, continue to wind twine through bark, tugging tight at the corners. Slowly, the sides of the two-inch-high baskets begin to rise, some too weak or lopsided. Says one woman, deciding to start over again: "No wonder you give the first one away." "People don't understand what it takes," marvels another woman, Ann Rankin. "It's an art form. What they were able to do with what came off the land. . . "

"The weaver sat closest to the fire for the light, and people would come over to watch. She had a captive audience. So nine times out of 10 she's a storyteller, too. If I had known that, I wouldn't have taken basket weaving so seriously. I was the shyest kid in class." As the women lose themselves in their work, eyeglasses teetering at the edges of their noses, Moon spins a tale giving the lowdown behind certain canine behavior. The legend is loaded with sound effects and hyperbole: "All that can hear me, come to my Potlatch!" she hails. There are party-throwing dogs and howling coyotes. But there's another story going on here, one having to do with Moon's audience. Back when the state's basket makers met at Evergreen, faced with the extinction of traditional designs and techniques, some weavers went to tribal leaders and asked permission to teach the craft to anyone who wanted to learn, Native American or not. To the dismay of some elders, many such requests were granted. Moon says it was like giving away Grandma's secret pie ingredient, but it ran deeper than that. Weavers with whom she had studied had shunned the idea. Resentment of non-Indian culture still haunted many elders who had seen relocation, disease, alcoholism and adoption unravel the threads binding indigenous societies.

"It's almost unheard of," says Darien Cabral, director of the Indian Arts and Crafts Association, based in Albuquerque. "New Mexico is pretty much the center for Indian art, and it's not happening here. Some of the tribes get very upset if people even copy the designs." But even while basket making enjoys a modest resurgence among Washington's younger Native Americans, Harvest Moon is among those who say it's time for the walls separating the craft from those outside the culture to come down. "My philosophy," she says, "is that the circle of the healing process is complete. We need to share our tradition." Mentored by her uncle, Harvest Moon was born Stephanie Cultee. Her Native American parents, both struggling with alcoholism, gave her up when she was still a baby. A German/Polish family adopted her. "It was a blessing for me," she says. "I wouldn't be where I am without them." Her grandfather had instructed her social worker to pass on to her adoptive parents Stephanie's Salish name, one meaning "light shining forth in the midst of darkness." At 15, she began calling herself Harvest Moon. At 17 she married a man of Norwegian ancestry and eventually had four boys. The two youngest now live with their father, whom she divorced nine years ago. That's when she officially became a professional weaver, she says. At 19, she met her birth parents - first her father, who died of a stroke shortly after. She met her mother at the funeral. During the service, she says, "My hands started shaking; they gathered around me and said, 'Don't worry - that's a good thing. Your father has given you a gift, in your hands.' I figured out it was basket weaving."

"He was putting the carrot in front of the donkey," she says. Cultee had a sly way of teaching her without her knowing it. He told her to make lots of little baskets. "I said, 'I don't want to.' I made a big basket and it turned out really ugly, so I got disappointed and quit. I said, 'This is a stupid art.' " But when the Burke Museum needed two dozen small baskets for an event, she filled the order, placing the completed baskets one by one atop her piano. She found herself lonely when the museum bought them all and they weren't there anymore. And something had happened. In the fall, when she started making large baskets again, she found that all those little baskets had taught her to make bigger designs. "I got my big-screen TV," she says. And she never doubted her uncle again. Along with Cultee, Moon apprenticed under a number of accomplished weavers, learning various tribal designs. Some of the designs are mind-boggling; she spends a day charting her work on graph paper before she begins.

But it's hard not to weave when the mood strikes, and conversely, when her oldest son joined the Navy, she couldn't weave for four months. "If something's upsetting me," she says, "what I'm feeling goes into the basket, and whoever gets it will feel it, too." In peak weaving mode, she weaves six days a week, 10 to 12 hours a day, old movies playing on the television as she works. My commute in the morning is from the bed to the couch," she says. The baskets emerge in a range of sizes, from cafeteria ketchup holder to large flowerpot. Some take a day to finish, others nearly a month. They're priced from $30 into the hundreds; the cost can surprise those unaware of the labor and quality involved, but she feels a bond with people who buy them. "(The baskets) come to life just like a baby," Moon says. "I see the people later, and it's like a reunion." Professional basket weaver: Even her kids can't believe it. "They go, 'Mom, when are you going to get a normal job?' They're teenagers, highly embarrassed." She sells at festivals such as Evergreen State College's Super Saturday, where she sold her first basket 12 years ago. Her work also has been recognized at Portland's annual Indian Arts Northwest festival, where this year there were 18 weavers among the 200 Native American vendors invited to attend, about double last year's number. Young Native American weavers are starting to emerge from the woodwork. "It's like a revival," says 22-year-old Skokomish weaver Lynn Wilbur-Foster. "Unfortunately, baskets have been under-priced and under-appreciated for a long time."

Wilbur-Foster says the profession is spiritually rewarding, if not necessarily financially. "It depends how dedicated you are," she says. She points to Moon's esteemed uncle, Richard Cultee. "He's been doing it for years, even when nobody was making them hardly at all. He's proof you can make a living at it. He's everything I hope I am in 60 years." Weaving baskets is an antidote to fast-paced living, says Colleen Jollie, former director of the Northwest Native American Basketweavers Association, which sponsors an annual weavers' gathering. In five years, the organization's membership has grown from zero to 500. "It's a way to put technology aside," Jollie says. "There's no way to do it quickly." Jefferson says some new weavers want to reclaim parts of their heritage nearly lost when the U.S. government forced Indian kids off reservations into Catholic schools. "They tried to wipe out all the cultural things, from the language down to the basketry and carving," she says. "They felt those things weren't what they needed to get by in modern life." But modernism does have its advantages: At this year's Indian Arts Northwest festival in Portland, Moon made her first credit-card sale. Times have changed for basket makers. Says Moon: "It's a combination of tradition and newness." Bark buffets "Oh," she says. "Makes my mouth water." Quickly, with her new axe and the mill owner's permission, she whacks at a log, splitting open its bark shell. She slides a hand underneath, wedging it sideways until there's room for the other hand, her palms flat against the bare wood, which is warm and damp, smooth as a guitar. With her fingers leading the way, she pushes downward along the length of the log. Her face tightens, the animation gone from her eyes, her focus in her hands.

"Look at that," she says, admiring the fresh inner lining. "That's nice." Back with the axe, then more wedging, pushing and peeling. The liberated stalks of bark form a growing stack on the ground. She carries them 100 feet and loads them into her aging car. With cedar bark season in high swing, she's been making numerous trips to the mill. "You can't go to a craft store and buy cedar bark," she says. "I used to chase down logging trucks, because I didn't know where they were going," she says. "One driver thought I was trying to pick him up. I said no, I just want the bark." Strips of cambium, the usable fresh layer underneath, are methodically peeled from their bark covering. She slices the cambium into consistent widths, then slightly oven-cooks it to both season it and kill any stowaway bugs. When you factor in the gathering, processing, dyeing and cleaning, cedar baskets don't seem so expensive after all. "Weaving," she says, "is just the tip of the iceberg." There's also the traditional method of harvesting, in which she takes her axe and requests a tree's permission before taking a two-foot strip of bark probably good for 10 little baskets. The patch will heal, she says, and eventually close. In her Quinault tradition, novice weavers are limited to one hand-width of bark from each tree; the practice helps conserve supply. "The longer you've been weaving, the more you can take," she says. She takes her quarry home to Tenino, southeast of Olympia, where she lives in a wooded clearing rife with ravens and hummingbirds. Just below is a burbling creek, her treasured neighbor; it's what brought her here four years ago from Redmond. The house is small and rustic. Baskets line the sills and the floors, and her "bible," a worn copy of a book appropriately called "Indian Baskets," leans against a wall. Folded strips of processed cedar bark hang in yellow bow-tie shapes from the rafters. This is her new classroom, where she teaches mostly adults recruited via local newspaper ads. The surrounding area is largely white; so are her students. Baskets aren't all she teaches: Kids like Chelsea and Shannon Eubanks, ages 8 and 6, and Anthony Lines, 9, learn to make cattail dolls.

They're only cattail dolls, but it brings up that issue again, about teaching outside the culture. For some, it's still a touchy subject, one people won't discuss even with their families. Others see the practice as a selling opportunity, with classes more likely to produce potential buyers than hordes of non-Indian weavers. Either way, a number of the elders who objected have since passed on. "They were so grief-stricken," Moon says. When she first started teaching, she explained to some of them that she was only sharing information that had already been published in books. That made them feel a little better, she says. Sometimes people, non-Indians, say to her, "I'm sorry for what we did to your ancestors," but she tells them there's no need to apologize, what's done is done. The current elders aren't as bitter as the old elders were. "They understand that change is good," she says. "Like a river, you have to keep moving and changing." Skokomish Indian Tribe Quinault Nation Tribes of

Washington The Progression of Basket

Weaving in the Southwest |

|

|

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. |

|

Canku Ota is a copyright of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

|

Sometimes

preserving tradition means jumping onto the battered horse she calls her car and riding 150 miles to a remote Snohomish

County logging town.

Sometimes

preserving tradition means jumping onto the battered horse she calls her car and riding 150 miles to a remote Snohomish

County logging town. Moon

says a tribe's weaver, being self-reliant, usually married the chief's son or other respected tribal member and

eventually was even excused from chores to avoid hand injury.

Moon

says a tribe's weaver, being self-reliant, usually married the chief's son or other respected tribal member and

eventually was even excused from chores to avoid hand injury. Even

though prominent weavers such as California's Elsie Allen, a Pomo Indian, were teaching white students as early

as the 1970s, the practice still puts Washington at odds with many of the nation's Indian artisans.

Even

though prominent weavers such as California's Elsie Allen, a Pomo Indian, were teaching white students as early

as the 1970s, the practice still puts Washington at odds with many of the nation's Indian artisans. She started

by working alongside her uncle, famed Skokomish weaver Richard Cultee. He'd point to his big-screen TV, she says,

and tell her, "Look - one basket paid for that."

She started

by working alongside her uncle, famed Skokomish weaver Richard Cultee. He'd point to his big-screen TV, she says,

and tell her, "Look - one basket paid for that." Her teachers

included Chehalis weaver Hazel Pete, Hazel Underwood (a fellow Quinault) and Lillian Pullen (Quileute). It was

Hazel Pete, she says, who warned that Sunday weaving would spell Monday misfortune. Sure enough, when Moon landed

a gig at Seattle's Folklife Festival, "I wove on a Sunday and got a traffic ticket on Monday."

Her teachers

included Chehalis weaver Hazel Pete, Hazel Underwood (a fellow Quinault) and Lillian Pullen (Quileute). It was

Hazel Pete, she says, who warned that Sunday weaving would spell Monday misfortune. Sure enough, when Moon landed

a gig at Seattle's Folklife Festival, "I wove on a Sunday and got a traffic ticket on Monday." Today's

basket makers, then, are learning to market themselves, developing promotional materials at copy centers and launching

Web home pages. At Bellingham's Northwest Indian College, students learn business technique along with weaving

and material gathering. "We have some excellent weavers, but they don't know how to market their product,"

says instructor Anna Jefferson, a Lummi Indian.

Today's

basket makers, then, are learning to market themselves, developing promotional materials at copy centers and launching

Web home pages. At Bellingham's Northwest Indian College, students learn business technique along with weaving

and material gathering. "We have some excellent weavers, but they don't know how to market their product,"

says instructor Anna Jefferson, a Lummi Indian. Sweat

springs from her cheeks and forehead. She grunts, groans in exertion. Sometimes, she says, it's like giving birth.

Finally, the strip of bark peels away, tearing away with a sound like a cracking coconut.

Sweat

springs from her cheeks and forehead. She grunts, groans in exertion. Sometimes, she says, it's like giving birth.

Finally, the strip of bark peels away, tearing away with a sound like a cracking coconut. "It's

something they don't normally get to do," says the sisters' father, Kevin Eubanks. "If it weren't for

Harvest, they never would have gotten the chance."

"It's

something they don't normally get to do," says the sisters' father, Kevin Eubanks. "If it weren't for

Harvest, they never would have gotten the chance."